Mapping and estate management on the early nineteenth-century estate: The case of the Earl of Aylesford's estate atlas

Contributions to the next volume are welcome. See the guidance for contributors and contact Editor Jason Mazzocchi. Also see the guidance for peer review.

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Kentish map-makers of the seventeenth century

Kent churches - Some new architectural notes

Mapping and estate management on the early nineteenth-century estate: The case of the Earl of Aylesford's estate atlas

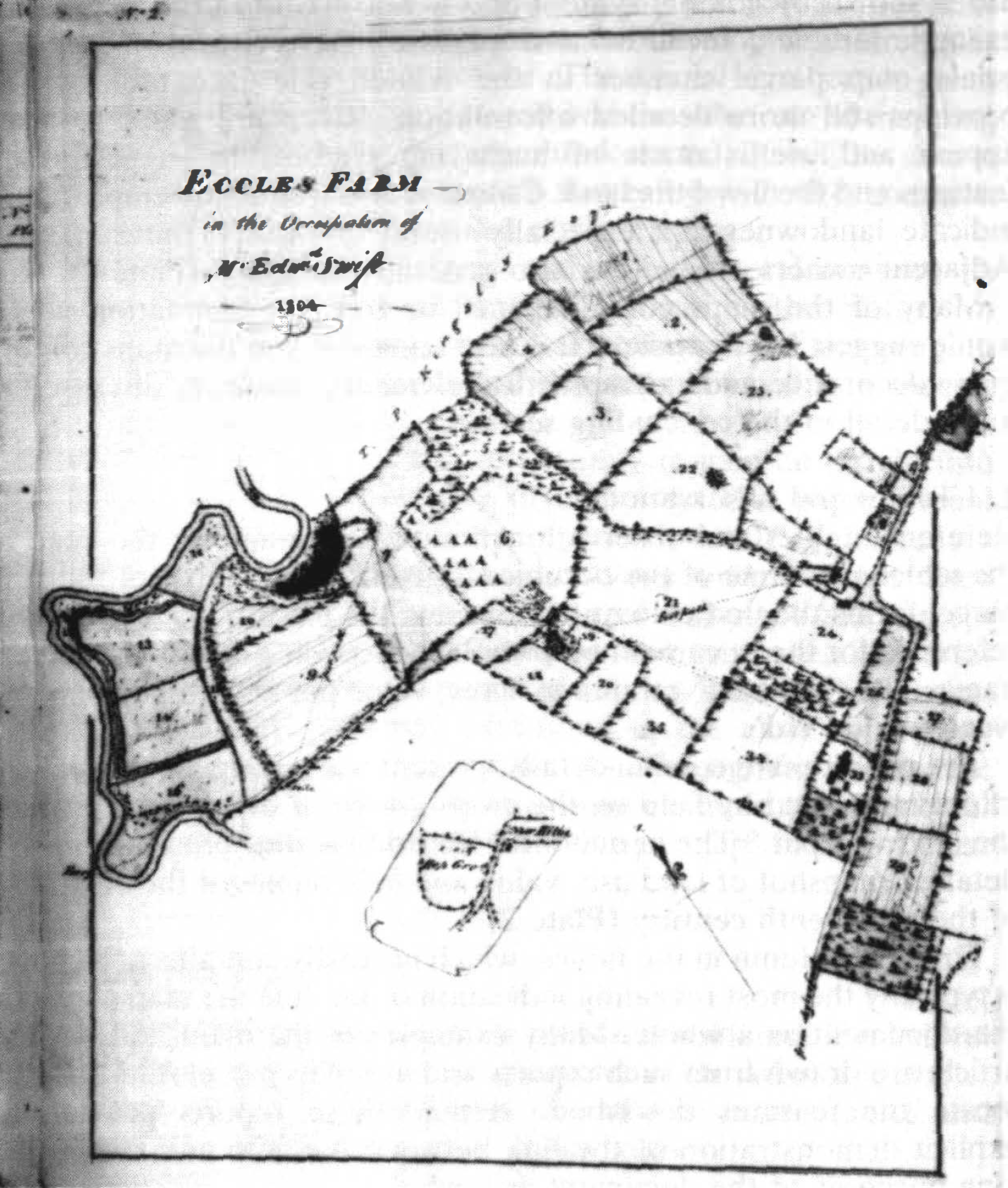

MAPPING AND ESTATE MANAGEMENT ON THE EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY ESTATE: THE CASE OF THE EARL OF A YLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS DAVID H. FLETCHER 1. INTRODUCTION Many general accounts have been written of the development and significance of estate cartography, but few have attempted to reconstruct in detail the precise purposes to which the maps were addressed. This paper is intended to provide such a detailed study of the range of strategies tackled by a set of estate maps. It is based on an early nineteenth-century Kentish estate atlas made by the surveyor R.K. Summerfield1 for the Earl of Aylesford.2 The atlas contains mapping dated 1805 and has subsequent textual revisions and map annotations to reflect the changing situation by 1825 and beyond. It is a large bound book with leaves about A3 size3 depicting the Kentish estates of the Earl of Aylesford in mid-Kent.4 The atlas is structured around a series of twenty-one maps each of which is followed by a table or grou of tables relating to them, and a series of reports and observations. The special significance of this 1 The entry in Eden's 'Dictionary of Land Surveyors' notes Summerfield's work back at least as far as 1798. His surveying commissions also encompassed work in Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk. Summerfield was also involved in producing enclosure maps, which are obvious examples of maps used actively to plan change. Source: (Ed.) P. Eden, Dictionary of Land Surveyors and Local Cartographers of Great Britain and Ireland 1550-1850. Folkestone, 1975. 2 C(centre) for K(entish) S(tudies) U234 E21. The atlas has no title, although the preface reveals its purpose. 3 The dimensions are 440 by 380 mm. 4 Lands shown are in the parishes of Aylesford, Boxley, Bredhurst, Burham, Detling, Headcorn, Hunton, Maidstone, Rainham, Stockbury and Thurnham. 5 For a full list of the estate maps in the Centre for Kentish Studies, formerly known as Kent County Archives, see (Ed.) F. Hull, Catalogue of estate maps 1590-1840 in the Kent County Archives Office. Maidstone, 1973. 85 DA YID H. FLETCHER book of maps is its rarity among estate atlases in containing substantial text. The maps read in conjunction with this text reveal, in precise detail, the range of estate management and development strategies employed or recorded by the surveyor. The special significance given to maps in this process may be inferred and thus the role of mapping in estate improvement may be better understood. It will be shown that the atlas embodied a range of strategies with the common ultimate goal of increasing the value of the estates. By setting the atlas in its local and more general context, its importance is shown, both as an artifact within the history of cartography and as evidence of the contribution of mapping to processes of estate management and development within a specific historical and regional setting. The atlas thus provides a rare opportunity to gain an insight into contemporary use and importance of mapping. This paper should thus have significance to a variety of audiences. It illuminates a source of local data on the physical landscape and the humanised environment. It also provides an indicator of contemporary perceptions of that environment, both material and symbolic. The atlas provides an insight into the attitudes of the landlord to the tenants and the management priorities prevailing in the early nineteenth century. Finally, the paper has more specific significance to the historian of cartography, since the atlas is an example of a particular manifestation of consciousness of the value of maps in a particular context. The structure of the atlas Before the broader significance of the atlas is considered, it is helpful to provide some explanation of the character of the atlas as a whole. The sequence observed throughout the atlas is maps, tables and observations and finally a sequence of summaries. 1. The maps The maps of rural properties are at a variety of scales between 1 :2000 and 1:10000. In most cases the unit of mapping is the individual farm comprising a part of the estate. There is an urban map at the larger scale of 1:990 showing a part of Maidstone in detail. The scales chosen allow the depiction of single units of the estate on the single pages of the atlas; whilst permitting the insertion of detailed information and subsequent annotation for each land parcel. The maps appear to have many trappings of cartographic competence. Most display a north point and although bearing no scale, when compared to modern topographical maps of the area 86 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS appear to have been drawn accurately to scale. On many maps, land use is shown by colour, symbol and is also written in in pencil: for example 'arable', 'meadow' and 'pasture'. Reference to the appropriate map parcel number in the related reference tables often provides still more detailed information. River and water features appear and use is made of hachuring symbols to suggest relief features and the lie of the land. Colour is also frequently employed to indicate landownership; especially useful in cases of intermixture. Adjacent owners of land are also generally indicated (Plate 1). Many of the maps contain pencil or red pen annotation which would suggest later revision. It is also apparent that the maps contain many decorative and extra-practical elements; these are discussed in more detail in the concluding section. 2. Tables and observations Reference tables and observations follow each map. At the head of the tables the name of the occupier is given. The number of the map parcel forms the first column, confirming the maps' role as anchor of reference for the document as a whole. Succeeding columns give field names; the 'Quantity' or area in acres; value per acre in pounds; and 'yearly value £sd'. The penultimate column details 'present use' giving highly detailed information field by field on the crops grown or other uses to which the land was put.6 The agricultural historian is thus presented with a detailed snapshot of land use, value and field names at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Plate 2). The final column in the tables, which normally contains a 'Report', is typically the most revealing indication of the role the map played in the document as a whole. Many examples in the main body of this article are drawn from such reports and use map parcel references to locate the features described. Hence, these reports provide an explicit demonstration of the link between the map and the improving purposes of the document as a whole. 3. Summaries The summary tabulations at the end of the atlas provide important confirmation of its overall purpose. The significance of the maps as the base of reference for these once again confirms their centrality to the document as a whole. 6 For example, the report for Harple Farm, the crops include oats, wheat, cinquefoil, barley, turnips, hops and wheat and beans. Other land uses indicated include bushes and heath, furze, yard, etc., fallow, feeding ground and mowing ground. 87 DAVID H. FLETCHER .EcCJJt Fr -) ,;. :,A,, (I"/,"' [I' ,,..,.s'""tJ,,,r -- . :; . ::; PLATE! .. Map of Eccles Farm in the occupation of Mr Edward Swift, 1804. This map is typical in its design and style of the maps in the atlas. The first summary tabulates the sales and purchases on the Kent Estate from 1805 to 1825. 7 The next sequence of summaries provides an overview of the whole of the earl's Kentish estates under the heading 'Estate Collected 1805. '8 Finally, there is an overall assess- 7 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 54. 8 C.K.S. U234 E21, pp. 55-57. 88 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS L.P..u» ,,,,# ......,., ,. ,;., 0-.,.rtll(i,- " ,l'JJ .u ., (M .......,.._ -· 7.:.,,, ♦ ONA•,.,,,-· -- --7 ,, 1¥,-,M, ,.,,.,,. .... PLATE II Ji" I .. .# ., -' II - .............. . i ,,,,, ,,;,J #I' -·"" J ., ,,,.._.,L ...,.-,;. .... ,I'll,., • .,,... _,,.,,, u1-,u ,y.- ,,..,,. ., . ,...,,,,, r---- ··r· ,,,,._, - .t, .,._ na, ,,,. "'i . ' ..,...,,.. . ,..,._ - a,.,-, ' (,...,_..,.,,.;. )',N#j .1J I 6-d N fJ,6,, AT .i.Ji !-' fJ A,,, .. - - )'.r, • -,,u ,-.,., . ✓ ,u ■ CJtHny I>,,,,.,. 4 . .J,1/ 11 lb-.1 1,/W - - 6. "71 a.. ,.,,.,.,,,.11,,,,J,,.6,y,. _,., ,.r.<, ;JI//. ,U"J'r,.# • M, At,,nw,..... _'u.,,:M . j'-r...,J n---v,J ., (-✓,fJv, ,,.,.., • • f;-, y.lrh; Y,1.,_.., .J?,, ., .Jilh..., _fr .INM' , · Jh •-..,.,en;, • .(.,_.,, a 'IJ,,t,.,..,,t_f' .F,r/; • J..wYr, . /:,IJ. IW,.,...., A.u;J 11 'No· J,• ,. 11:,,,A1t,,,. • ,,.,. , Al-??,JJI,-"' , 7...,,,.,-,. .,J., "t .,,., ,. WN-" -,i,},/.L ... 44/d, • ,. H,:,,., "►1 -I .,.4" Jh ,t,• • 1-;r,tfl.rh, l,,tt.1 - '.? ) -.z:✓-. .c....,., ,,rJ-)(. :,.,l,,,1,!,,,:;,L ,,,IJ- .;,_ /1,, ,,,, ,#/4., I Z:. . , ... , _,,,,,,, ,I. ,/• ::,,: .. , o,.H,,,.,<' ,, , .,., ,,, •: I.✓,_, I ,;, .,,; ,, •. J / .-,n. ....,,,., h... )' -'... ,-Z,.-. "'-u.../... .....,. .... -j. .,,,• ,u.r,·- 1';;: :, ... .-.J;--, -#lliH. b..,,,.., ,,.,,,--1.,,,,,,. ;+ ' Jh..;.1· -........,- ;.,.-AJ:- . ',. 4.., /' Y,£ ,,1/.,-,,J,. <., ; . '; ..... ff ,£_., ill .. u;., -=-,. N ..." .......:. r...i Referencees setnabtilael ifno ri nttherep rLeotidngge t hFeasrem t.a bRleesf earnedn cthe e tcoh atnhgee sa ctchoemy pparnoypionsge dm. ap was ment of the area of the estate, both wooded and farmland.9 The total of the Earl of Aylesford's Kentish estate is given as slightly more than 4921 acres, not including purchases of land. The main purpose of this summary, however, would seem to be to show how the estates have 9 The total area of woods in hand including warren and reeds is just over 1464 acres. The total area of other lands described as 'farms &c' is 3456 acres. 89 DAVID H. FLETCHER grown in the 20 years to 1825. It is revealed that there has been an 'increase by estates purchased more than sold' of 140 acres, which brings the total area of the estates in 1825 to 5061 acres. The surveyor, R.K. Summerfield, is thus able to paint for the Earl of Aylesford a picture of a healthy and growing estate. There is objective proof to be found that the estate is growing in area and value. These final totals are based on more detailed summary tables, all of which are based finally on data taken from cartographic surveys. The centrality of the maps in providing objective data could not be plainer. The context of the atlas 1. Local context and Aylesford estate history The first earl, the Rt. Hon. Heneage Finch, P.C., gained the title of Earl of Aylesford in 1714, at the time of the accession of George I, 'an estate having been left to him there, with a large fortune by his wife's father', Sir John Banks of Aylesford. 10 This was the beginning of the Aylesford estate in its later form. When Summerfield produced the atlas, the fourth earl held the title.11 The estate was already mature by this stage, and Summerfield's task was to transform an existing landed estate rather than create a portfolio of property. It would seem that Summerfield was the first land agent working for the Earls of Aylesford to make such an atlas integrating maps with descriptive text for the purposes of estate transformation. The 1805-25 estate atlas has a direct predecessor. In 1786 was produced the 'Reference to the earl of Aylesford's Kentish estates' surveyed by Thomas Wedge.12 This large bound volume has a format almost identical to that of the 1805-25 estate atlas, containing a series of tables, each relating to a different farm on the Aylesford estate. The furthest left column in the tabulation is headed 'Plan', making it clear that the volume relates to some maps, although these could not be traced in the Centre for Kentish Studies or in other repositories. In any case, the principal difference is that the volume contains no maps and thus does not forge such a close link between maps and linked text. Later estate documents reveal that no rival to Summerfield's atlas 10 Dictionary of National Biography, v xix, 1889. 11 From 1777-1812: Source: (Eds.) C. Kidd and D. Williamson, Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage, London, 1990, 78. 12 C.K.S. U234 E20. 'Reference to the Earl of Aylesford's Kentish estates' surveyed by Thomas Wedge 1786. 90 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE AT LAS was produced. As will be shown, there is internal and external evidence that the atlas continued to be used for a number of decades after its production. Indeed, the atlas appears to have been in use almost until 1884 when nearly all of the Kentish estates were put up for sale under a 'disentailing act', 13 and the earl's principal seat became Packington Hall in Warwickshire. 2. Estate management It is instructive to understand something of the general historical context in which Summerfield produced the atlas. In referring generally to the changes in estate management around the end of the eighteenth century, Thompson notes that 'The economic pressures for changr! were present in the shape of increasing competition in farming and increasing difficulty in maintaining rent levels, which called for greater attention and discrimination in management as well as properly directed landlords' investment ... ' 14 The Aylesford atlas could be seen as a local example of such greater discrimination in management and care over investment. Although administrative arrangements were seldom uniform and efficient business-like styles far from the norm, nevertheless, Thompson argues 'The spirit of improvement ... meant, for landowners, that the estate was given a positive role as a unit of management. Through investment and supervision of farming practices the task of managers under such a system was to encourage technical and economic efficiency.' 15 Summerfield can be seen as such a manager and the atlas as his cartographic instrument. There was a growing class of land agents of which Summerfield was one. Thompson notes that 'Professionalisation was in part the product of those forces which were making improvement, efficiency in administration and in management of resources, both more attractive and less avoidable, and which were thus creating careers for expert land agents.'16 Despite the increasing importance of these land agents, Thompson notes that on important matters it was necessary to consult the 13 C.K.S. U234 L4 'The Earl of Aylesford 's Estate Act, 1882 ' 45 & 46 Viet. 14 F.M.L. Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, London, 1963, 182. 15 Thompson, 1963, 154. 16 Thompson, 1963, 156. 91 DAVID H. FLETCHER landowner: 'the ultimate decision always rested with the owner, and no agent was ever authorised to embark on a great project without the express sanction of his employer'.1 7 The tenor of Summerfield's atlas proved to be no exception to this pattern, its Preface, in particular, showing that the atlas was intended to provide the landlord with an overview of his estate. On such a basis, approval for changes made and assessment of the wisdom of future changes was facilitated. Thompson goes on to argue that whilst 'management was a function vital to the state of agriculture . . . yet the records often reveal little about its quality ... '. 18 This study of the Earl of Aylesford's atlas could be seen as going some way to remedying this situation.T his account shows the operation of a specific management tool in action and evaluates its significance and quality. 3. Estate mapping Blakemore and Harley have lamented the tendency of much past scholarship in the history of cartography to be merely morphological: 'as just another source for the reconstruction of some past event or landscape feature.' 19 In contrast, Skelton argued that the true role of the history of cartography is to 'trace the development of man's knowledge and ideas about the earth and the graphic forms in which he has expressed them'. 20 The present paper is offered as a contribution to the types of study advocated by Skelton and others. It regards the relationship between maps and socio-economic change as reciprocal, maps being seen as having a dynamic role in shaping society rather than being regarded merely as passive indicators of the status qua. There was a considerable increase in the production of estate maps from the early eighteenth century, written records having previously been the norm for estate management. The significance of this paper to the cartographic historian is in its precise reconstruction of the estate management and development strategies to which the atlas was addressed. The significance of cartography can only be appreciated in this broader context of use, and the special value of this atlas is that the text associated with the maps permits such a reconstruction of the fuller context. 17 Thompson, 1963, 175. 18 Thompson, 1963, 182. 19 M.J. Blakemore and J.B. Harley, 'Concepts in the History of Cartography', Cartographica, xvii (4) 1980, 1. 20 R.A. Skelton, Maps: a Historical Survey of their Study and Collecting, Chicago, 1972, 62. 92 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS Questions and mode of analysis There are essentially three main questions pursued in this paper. First, the general purpose of the atlas is isolated. Following this, a more detailed reconstruction is made of the specific purposes to which the maps and related texts were addressed in pursuit of this common goal. Finally, and of most significance to historians of cartography, an evaluation of the role and significance of the maps in the atlas as a whole is attempted. In order to determine the general and specific purposes of the atlas, a detailed scrutiny was made of the use of the maps and related text in specific use-contexts. To this end, the following categories of purpose were isolated: rationalisation of landholdings and transport infrastructure, recording and appraisal of resources, and planning and display of works of improvement. The way in which the maps were used and their indispensability provide an index of the significance of maps in the processes of management and estate transformation to which the atlas was addressed. The presence of the maps in the atlas does not explain their precise significance and centrality. More detailed scrutiny of the maps and associated written texts is necessary in order to determine how the map was perceived and intended to be employed. Such an assessment is made in the more detailed consideration of the atlas which follows. Maps have a unique ability to record ideas and information about landscape succinctly. This special property is recognised by Beresford who in reference to a set of maps made for All Souls' College, Oxford argued that 'all the details of position, size and ownership which had previously needed the verbosity of a long roll or bundle of parchment were now concisely stated and the whole disposition of the estates lay before the owner's eyes. '21 An examination is made in the present paper of the extent to which the inherent advantages of cartography were recognised by Summerfield in drawing up the atlas. An evaluation is made of the deployment on the maps of colour and naturalistic symbols to achieve a graphic portrayal of information. The use of reference numbers and letters as well as colour schemes to forge a link between the maps and the text is examined in order to evaluate the extent to which the reports and observations were map-dependent. 21 M.W. Beresford, History on the Ground: Six Studies in Maps and Landscapes Gloucester, 1984, 66. ' 93 DA YID H. FLETCHER 2. THE PURPOSES OF THE ESTATE ATLAS The Preface to the atlas provides some clues as to its intended general purpose and the role of the maps within it. The opening passage indicates that the volume was commissioned 'By direction of the late earl of Aylesford this book of maps, references etc. to the Kent estate was made in the year 1805 . . . ' Summerfield notes that since the main body of maps were produced around 1805 'so many important changes have taken place by purchase, sales, lettings &c as to render, I think a revision both necessary and useful. This I have done on leaves introduced between the maps, tracing occurrences as they have happened and showing the position of the property at the present day ... '22 The maps were thus intended as a basis for the display of changes to the estate. That the atlas was also intended to serve as a compact ready reference to the estate is made clear in the final passage where Summerfield says 'Should reference hereafter be needful, your lordship by having this book by you can readily inform yourself on any subject and it will also I trust give your lordship a general knowledge of every part of the estate. '23 This rhetoric reveals that the general intention of the atlas was to provide Lord Aylesford with a spatial overview of his estates. Through a detailed examination of the maps and related text, the accounts which follow seek to reconstruct the more precise strategies to which the atlas was addressed, and the significance of mapping in each case. 1. Rationalising the physical layout of the estate The first category of use to be examined is the role of the atlas in rationalising the physical layout of the earl's property by means of exchange, sale and purchase and by rationalisation of roads and paths. These various operations had the common goal of eliminating inconvenient, detached and unconnected pieces of property, and reshaping the estate into consolidated holdings to make the whole easier to manage and more profitable. The evidence for this objective is clear from inspection of the maps and from many of the reports which follow them. 22 C.K.S. U234 E21, Preface. 23 C.K.S. U234 E21, Preface. 94 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS The 1805 Report on Meirs Court Farm states that 'The detached situation of the lands comprising this farm are a great inconvenience . • . '. 24 It would be particularly valuable to acquire this land because it is 'a deep loam and very good wheat and bean land ... ' Summerfield points out to the Earl of Aylesford that his lands 'and those of the earl of Thanet are very much intermixed and exchanges I think might be made to mutual advantage'. The extent of this intermixing is evident on inspection of the map and hence the good sense of the changes proposed is made graphically obvious. The map depicting the Boxley Abbey estate likewise employs different colours to make graphically obvious the benefits of a recent exchange.25 The map bears an explanation of the colour scheme which is repeated in the account which follows. It is noted that the Boxley Abbey Estate now makes a large, contiguous land-holding: something which is only made fully apparent from sight of the map. It is remarked that 'The pieces coloured yellow were received in exchange with Lord Romney which unite the Abbey Land, Sandling, Bourley and Tyland Farms all in one ring fence, so that this part of your Lordships estate (looking at it in the aggregate) is unquestionably of greater value by the accession of this exchange and the Abbey Estate.26 The use of colour to differentiate kinds of land or landownership draws on the unique ability of the map to present a graphic portrayal of a spatial pattern (Plate III). A common theme in the exchanges described above is the value of assembling contiguous and compact land holdings. The map of Little Buckland is used to good effect to display interruptions to otherwise nicely contiguous holdings showing a public road which directly cuts through this part of the estate. 27 The accompanying report argues that 'The thoroughfare through Mr Pack's yard to the lower orchards and the river is a great nuisance and a depreciation to the Little Buckland property. '28 The report goes on to argue that 'the compactness of the farm and its contiguity to Maidstone with the turnpike road passing through increases considerably its value . . . '. 29 This compactness and the position of the road are clear on inspection of the map. The report on Great Buckland Farm notes 'the very convenient 24 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 24. 25 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 19. 26 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 47. 27 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 11. 28 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 28. 29 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 29. 95 ,. DAVID H. FLETCHER // - l,-,./4. ..,,,, PLATE III Map of the Boxley Abbey estate. As its footnote indicates, colours are used to distinguish existing property from that acquired by exchange. 96 THEE ARL OF AY LESFO RD'S ES T ATE ATL AS situation in which the land lies to Maidstone ... '.30 This proximity to Maidstone of one side of this manor is made apparent on inspection of the map. Summerfield asserts that he has 'not the least doubt [that] the land laid down and continued in pasture, and let in two or more lots to Maidstone would make at least 150 pounds a year more than the present rent.' It is evident, once again, that Summerfield's underlying motive is to raise the value of his master's estate. The priority of amassing contiguous land-holdings close to the town of Maidstone would appear to have influenced sales and lettings policy as the following report on Newnham Court Farm makes clear. ' The four pieces nos. 30, 31, 3 2 and 33 called Goslings are nearly a mile from the House: Notices were served Mr Neale last year to quit them under the intention of selling, but as that seems now to be given up, I thought from their contiguity they would let much better to Maidstone and be no material injury to the farm.' 31 Once again the indispensable role of the maps as a means of reference and a medium with which to display a point is apparent. Spatial rationalisation as a basis for further improvement Spatial rationalisation was often seen as an essential first step before other kinds of estate improvement could be regarded as economically feasible. The maps played a crucial role in this process, both in planning and executing the initial spatial rationalisation and in planning and executing the subsequent works of improvement. In his report on Burham Court Farm, Summerfield makes it a priority to acquire certain land before improvements to the drainage defences would be justified. It is argued that 'it would be a great improvement to this farm (which is short of meadow and pasture), if the properties in the salt marsh and common meadow adjoining the river ... could be obtained either by exchange or purchase, so as to make it worthwhile to embank the whole which could be done at a very moderate cost as only one sluice would be required ... •32 The map to which this report refers,33 shows in distinct colours the land of Lord Aylesford and that of Sir S. Chambers, the adjacent owner, to illustrate the desirability of the proposal. The report forges a link with the map clearly stating that 'The red colour is your lordships- that coloured yellow is by purchase of Sir S. Chambers.' 3° C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 35. 31 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 16. 32 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 10. 33 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 3. 97 DA YID H. FLETCHER The account of Burham Street Farm34 provides another indication that spatial rationalisation was seen as a prerequisite for later material improvements. The report first notes before the enclosure of Burham Common in 1815 'the pieces of land coloured red were the only property (excepting the woods) belonging (on the Burham Hill) to the estate. '35 Colours are used to distinguish the subsequent purchases, it being noted that 'The pieces coloured yellow were purchased in 1815 of Sir S. Chambers and Mrs. Lane for £367.15.6- Those coloured blue were purchased of Mr. Dunning at £1200.' It is possible to make a precise reconstruction of Summerfield's motives in uniting the property. He states that 'The object of these purchases was to unite the whole property into one farm, the large tract of common otherwise would have been of very little value, and the detached pieces (coloured red) were returning scarcely any rent.'36 Having thus united the property, Summerfield himself as the tenant cultivated 'and grub up the flat tract of common land on the hill, also the furze fields Nos. 1 and 2 and to bank and make new fences against the road and the new allotments . . . ' As a result, Summerfield claims that 'The quantity of the land cleared by me and brought into cultivation is 71 acres, exclusive of hedges grubbed up and strips of waste.' The location and significance of these purchases and subsequent works of improvement can only be perceived on inspection of the map. Thus, the position of the map is once again confirmed as central. Improvement of roads and paths The maps and internal documentation of the atlas reveal that in addition to rationalising the spatial layout of the property, Summerfield also used the atlas to plan or record rationalisations of the transport network. At the smallest scale, the map of Harple Farm is used to show the good sense of a footpath diversion scheme.37 In the accompanying report,38 it is noted that 'Major Best wishes Lord Aylesford's leave and assistance to alter the course of [the] footpath, which would certainly improve both estates and I think would not inconvenience the publick.' The map shows the course of the existing and proposed 34 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 52. 35 The brackets appear in the original text. 36 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 52. 37 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 6. 38 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 19. 98 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS new footpath, thus making graphically clear the sense of the proposal to the peruser. There is an added note in red ink to the effect that 'Sept 1826 ... This has been affected'. This confirms that the atlas was used as a working document in which such changes were planned, demonstrated and recorded. Much the same purpose is evident in the map entitled 'Land purchased under the Burham lnclosure'.39 The text under the map explains how a short access road was made through the Burham enclosure to ease the passage to the earl's land. 'The Commissioners of Burham lnclosure having a power to sell common land by auction to pay expences, it was judged advisable to buy the lots comprising the 23a (cres) 3r(ods) 17p(erches) shown above; which was done for the sum of £680. A short and direct communication was then established between the Burham Woods and the turnpike Road; the access otherwise being difficult and circuitous.' This access road is clearly visible on the map, and its good sense is made more apparent by inspection of the map. 2. Resource inventory and evaluation It has been shown that the underlying motive for the rationalisations of landholdings and transport infrastructure so far considered was to enhance the profitability of the estates. Another essential element in Summerfield's exhaustive evaluation of the assets and organisation of the property was the production of an accurate and detailed record of its material resources. The use of the maps and linked text for resource inventory and evaluation may be seen also as a part of the general strategy of the atlas, to increase the value and profit potential of the estates. Agricultural resources Soil type and condition are an essential element of the agricultural potential of the land. There are many indications of soil and geology in the atlas. Characteristically, the maps play an indispensable role, since where soil and geology are not indicated directly on the maps themselves, they are often recorded by means of map reference in the associated text. The report on Eccles Farm is a case in point. 40 It is indicated that 39 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 21. The map indicates the lands belonging to the Wardens of Rochester Bridge and those already belonging to the Earl of Aylesford. 4° C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 5. 99 DA YID H. FLETCHER PLATE IV C L > /,,, LOftO.B .F.UL"ll , u,., .. ... :r.;.. •• t"e. ,,. ' I Map of the Lodge Farm in the occupation of Mr John Charlton, 1804. Agricultural land-use is distinguished by colour, texture of shading and pencil annotation. 100 THE EARL OF AY LESFO RD'S ES T ATE ATL AS 'the soil on this farm varies much, on some parts rather stoney; on others a darkish loam with a small mixture of black sand. The Reed Hills Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 23 are a cold clay but would be improved by drainage.I n the Lower Reed Hills Nos.1 and 2 is good white brick-earth which runs a considerable depth.' The map of the Lodge Farm41 is typical of the maps in indicating agricultural land use by colour, texture of shading and by pencil annotation of its use as pasture, meadow or arable (Plate IV). The related report provides an evaluation of the agricultural resources, noting that 'the soil on the upper parts of this farm is a good dry loam though rather light, the lower fields adjoining the meadows are sandy and somewhat inferior ... '. 42 The agricultural potential of the land is also discussed, it being noted that 'The meadows produce heavy crops of hay, but the quality of those adjoining the river is coarse'. Reference to the map is essential to determine the location of the meadow lands. Mineral resources Chalk was an important mineral resource on the estate. The report on Burham Court Farm uses map parcel numbers to locate it, noting that 'The fields No. 1, 2, 20 and 21 contain an inexhaustible mine of chalk esteemed the most valuable for making lime . . . '43 Once again, assessment of the financial value of this asset is central to this task, Summerfield observing that 'The lime is much in demand and the profits are said to be great.' The future sale potential of this resource is also considered, it being observed that Messrs. Lee of Greenwich have expressed a strong interest in buying or hiring the Burham Court quarry. Summerfield again makes reference to maps essential to his account suggesting that if such a transaction were arranged, 'they would establish their kilns at a* which is very firm ground and every way favourable.' The asterisk in the text is used to indicate a point shown by an asterisk on the map where the kilns are located. Details of the location and extent of mining leases are also recorded using map parcel references. The report on the lands lying on the west side of the River Medway describes how Messrs. Bensted 'became tenants to Nos. 2, 3, 4 and 5, the pieces then unsold, containing 24 acres upon an agreement for a lease of 14 years at a rent of £150 with permission to quarry under specified restrictions in regard to quantity of surface, depth and properly filling and levelling the parts excavated ... '44 41 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 1. 42 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 1. 43 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 10. 44 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 36. 101 DAVID H. FLETCHER The atlas reflects a concern with safeguarding the future quality and hence value of the property, noting the imposition on the Bensteds of a duty to farm the part not quarried 'in a proper husband-like manner'. The account also records that having exhausted the quarrying capacity, in 1814 the Bensteds 'applied for a new quarry and a second agreement took place for the field occupied by Down containing about 7 3/4 acres adjoining the road leading from the London Road at Great Buckland Gate to Barming Heath (No.1 4 on plan No.1 4) ...T hey have excavated most of the stone quarry and applied last year for the piece at the east end (No. 16) ... ' The stipulations which follow concern how the land is to be used and map parcel references continue to be the mainstay of the account, it being argued that 'A great deal of labour and expense is still necessary to fill up and render the present quarry (No. 14) what it should be ... it is made a particular injunction'that they shall fill up and make good No. 14 and not be allowed to excavate more thn 3 acres of No. 16.' 45 Timber resources The atlas also contains many references to the timber resources on the earl's estates. As well as providing a cartographic resource inventory, the related passages of text often set out a recommended course for future timber management. This again confirms the role of the atlas as an active agent, safeguarding the quality and hence future value of the estate's resources. Once again, the centrality of mapping to this function is manifest. The 1805 report for the Lodge Farm states that 'There is a great deal of very fine elm timber on this farm and very well-preserved. The land is well-cultivated and fences well kept-up, in fact Mr Charlton is an excellent tenant'. 46 The spatial disposition and extent of this woodland can be seen on inspection of the accompanying map where it is shown by the use of tree symbols. The 1825 account of Chesnut Woods also gives an evaluation of the timber resource and of the implications of local soil conditions for its potential quality. It notes that 45 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 37. 46 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 1. 102 THE EARL OF A YLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS 'These parts of the Chesnut Woods along the valley on both sides of the Maidstone Road are valuable producing both timber and underwood very good, but the hilly parts are a very light sandy soil, return but little and are incapable of improvement ,47 The locations of these resources can be seen on inspection of the map. An exchange of woodland is also recorded. Summerfield reports that 'In (or about) 1820, Shrubbers Wood colour'd red containing Oa( cres) 2r( ods) 20p( erches) was given in exchange to Mr Jno. Lake for the piece colour'd blue in equal quantity . . . '48 Summerfield argues that as a result both estates have been improved, by which he means have increased in value. It is once again apparent therefore, that Summerfield is keen to convince his patron that he has served him in raising the value of his estate. The special potential of the map to use colour to differentiate land is again successfully exploited. 3. Works of improvement Having been appraised, measured and assessed, resources could be developed and modified. It is clear from the examples which follow, that Summerfield used the atlas not only as a record of the earl's landed wealth, but also a tool for its improvement. This furthered the atlas' ultimate goal of raising the value of the estates, and Summerfield made good use of the maps to this end. Drainage and water supply The management and improvement of water supply played an important part of the dynamic purposes of the atlas. The use of the maps in this active process of estate improvement was again evident. As an example, the report on Eccles or Roe Place makes a brief cost-benefit analysis of river defence improvement. 49 The text is once again dependent on map parcel references to make the suggestions intelligible, again demonstrating the centrality of mapping to the process of estate improvement: 'The meadows No. 13 and 14 are defended from the river by an embankment and about 7 or 8 acres of No. 16 might also be embanked, the cost of which with a sluice near the river against No. 14, would be about 60 or 70 pounds. If such were done the land would be worth 25 pounds per acre more than it now is.' 47 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 43. 48 Page 43: under the heading 'Exchange'. 49 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 6. 103 DAVID H. FLETCHER Similarly, the 1805 report on the Lodge Farm50 demonstrates the increased rental value accruing from improvements to the flood defences. The subsequent report in 1825 proceeds to use map reference numbers to locate the remedial defence works. 5 1 Summerfield notes that 'In 1809 an embankment was made against the river from No. 5 to No. 21, and stop gates placed in the ditches, whereby the floods and tides that inundated and did the meadows so much injury were kept out. In consequence of the certain improvement that would take place, the farm was raised from £250 to £350 per annum ... The map of the Lodge Farm was made in 1804 and thus it was available as a planning tool for these improvements five years later. The map thus had a clear role in enhancing the profitability of the estate. The large-scale map of part of the town of Maidstone, 52 played a key role in Summerfield's attempts to justify the reimposition · of lapsed charges for water supply. Summerfield explains that 'On the plan is sketched the situation of the fountain, the pipes and collateral branches; the small dotted marks show the situation of those houses with the tenants names who use the water.' The map was thus used to show the position of the water supply and indicate which local property holders could be charged for its use. Although no payments had been received in recent years, it was proposed to fix annual charges to each house having access to this resource. Urban improvement The report on the town of Maidstone53 describes the thinking behind the road improvement scheme illustrated on the accompanying map.54 This new road scheme can be seen to be part of a larger programme to raise the value of this urban part of the estate, since the report begins by considering the best market strategy for selling some land close to Maidstone. Summerfield's scheme proposed the cutting of a new street and, to this end, the map was his main tool of demonstration. This would appear to have been another attempt to convince his patron, the earl, that his schemes had his best financial interests at heart. Summerfield recommended 5° C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 1. 51 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 2. 52 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 16. 53 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 39. 54 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 16. The map is centred on the Earl Street area of Maidstone. 104 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS 'selling the property within the town of Maidstone from the very low rents it returned being mostly very ancient houses gone to decay, and not worth repairing, also to the valuable situation of No. 9 as building ground through which I had proposed a new street to be cut from Week Street to Havock Lane as coloured red.' The map depicts part of the town centre of Maidstone and is selective in the detail it portrays, being restricted to detail immediately relevant to the purposes indicated and referred to in the text. It is possible to reconstruct Summerfield's rationale for the map from his account.55 Summerfield reports to the earl that just before 1803 he made a survey and plan of the part of Maidstone between Earl Street and St. Faith's Green and suggests that 'if a new street was cut from Week Street through to Havock Lane (with two passages: one to communicate with Earl Street, the other with St.F aith s' Green) the whole of this square would convert into valuable lots for building land, and if let on 60 or 90 year leases without any expense to your lordship would probably increase the rents several hundred pounds a year ... The map shows the 'Proposed new street in 1805' and it is explained in the text that 'The light red colour shows the proposed new street and passages and the red dotted line the proposed lots.' (Plate V). This vivid portrayal makes the proposed new road the most immediately apparent feature on the map, which is appropriate given its importance in the projected scheme. The text of the report indicates that this new road was expected to increase the profitability of this part of the Earl of Aylesford's estate. Summerfield again shows his mastery, not only of cartography in general, but also of skills in selection and highlighting of detail in its deployment. 3. CONCLUSION This article has examined the contemporary significance of an early nineteenth-century book of estate plans and linked text. Its special value derives from the presence of this internal documentation. This permitted a detailed scrutiny of the range of strategies employed by Summerfield, the surveyor, to further the general goal of raising the value and securing the continued prosperity of the estate. There were two linked objectives in studying the atlas. These are intended to have significance respectively to two main audiences: students of history in general, and students of the history of cartogra- 55 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 42. 105 l' DA YID H. FLETCHER PLATE V 1-, ✓ 4 ,.._ , _....,,.......,....,...,.....;..,."""I"....,......,...,,,'" r_...,._ __ ... ' • • Map of Maidstone indicating Summerfield's proposed new street in 1805, intended to raise the value of the property as lots for building land. 106 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS phy. Of general historical significance, the range of strategies employed by Summerfield to improve the Aylesford estate was reconstructed in detail. Of particular significance for the historian of cartography, the specific role and significance of the contribution of maps in these processes were examined. Although a range of apparently passive purposes as well as dynamic roles has been assigned to some of the tasks undertaken in the atlas, it is plausible to regard all of the functions as serving the ultimate goal of raising the value of the estates. The group of purposes classified as resource inventory and evaluation, normally involved an examination of the future potential and stipulations for careful stewardship in the future. The indispensability of mapping in the volume as a whole seems obvious from its inclusion of maps. However, part of the purpose of this account was to show exactly how maps were used to pursue the strategies described above, and reveal their centrality. The maps, in conjunction with the written reports, had a singularly valuable role for many of the tasks which Summerfield allotted them. The map has a unique ability to represent spatial patterns. Summerfield appears to have recognised this property by frequently employing them to make a graphic display of the problems of scattered parcels of landed property, and to show the effects of subsequent enclosure. The map can also show the relative location of features, and, as such, was used by Summerfield for locating resources. Maps were also used to demonstrate the value of proposed and effected improvements. The map could provide a powerful graphic display of the sense of a proposal or a scheme already completed. This could be achieved in a number of ways and the efficacy of these methods has been examined. Colour was used to differentiate land use, land-ownership and other characteristics. In addition, symbols and background textures were also employed to enhance the legibility of land use information. Reference numbers and occasionally letters were also used to designate land parcels and other features. The centrality of the mapping was clearest when it formed the anchor of reference in the associated text to colour schemes and parcel reference numbers used to locate features. Such crossreferencing was a common feature of the atlas, and, indeed, in many cases, the sense of the text would be lost without inspection of the designated features as located on the map. Even in cases where no explicit mention was made of the maps, features described in the text could normally be located on the maps, and the significance of their relative location appreciated. The maps can, therefore, be seen as indispensable in pursuit of the practical tasks to which the atlas was addressed. 107 DAVID H. FLETCHER The symbolic significance of the atlas The land and the wealth which derived from it formed the material basis for the social position of the earl. It is equally apparent, however, that in addition to these practical purposes, the atlas also exudes certain abstract values, in terms of pride of ownership and concomitant social status. It is necessary to examine these nonpractical symbolic functions in order to gain a holistic appreciation of the significance of the atlas and of the maps within it. Kain56 argues that land ownership as displayed in the 'property map' was a mark of social status. This atlas can be seen as a tribute to the splendour of the Earl of Aylesford's estates. It provided him with a record with which he was literally lord of all he surveyed. This intention is confirmed in the preface in which Summerfield boasts: 'Your Lordship by having this book by you can readily inform yourself on any subject and it will also I trust give your lordship a general knowledge of every part of the estate.' Rights in land and to resources are recorded for practical reasons, but in addition they served further to confirm the local socioeconomic dominance of the earl. This is illustrated by assertions of ownership rights such as in the report on the Lodge Farm, where it is clear that although Mr Cutbush may be the tenant, still 'Lord Aylesford reserves the privilege of using the wharf at all times' .57 The symbolic,: functions of the atlas were expressed in its decorative style. The whole document is executed in a neat and clearly presented form. The maps especially, could be considered as works of art, involving as they do, many ornate touches, often including elaborate cartouches. Where there are outlying parcels of property to be shown, this is normally done in insets drawn as impressionistic scrolls. A pleasing balance of colours is achieved in most maps despite the fact that the primary role of colour is probably to distinguish land use or occupier. These artistic elements all add to the image of the atlas as a manifesto of the strong social and economic position of the Earl of Aylesford. Longevity A final confirmation of the significance of the atlas is indicated by its longevity. The atlas was produced between 1805 and 1825, but 56 R.J.P. Kain, Maps and Rural Land Management c. 1470-c. 1670 1986, Draft to be included in volume iii of J.B. Harley and D.A. Woodward, The History of Cartography, Chicago, forthcoming. 57 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 1. 108 THE EARL OF AYLESFORD'S ESTATE ATLAS continued to be used and valued for decades after. Indeed, it was Summerfield's intention that it should serve as a working document. As his Preface states, intermediate revisions were recorded on leaves introduced between the maps tracing occurrences 'as they have happened'. 58 For example, on the map of Tyland and Bourley Farms,59 details of subsequent sales are added in red pen, whereas on the map of Bredhurst Farm red ink is used to record land use change and planning of such alterations. The map of Little Buckland Farm,60 shows in pencil the land sold to the railway company in 1866, indicating that the maps were still in use sixty years after being drawn. The report on Chesnut Woods61 also shows that the atlas was in use as late as the 1860s, it being remarked that the woods were sold in 1862. External documentation also confirms that Summerfield's atlas was still valued as a source of information long after it was produced. An estate document describing the underletting of Burham Court Farm,62 dated 1856-70, includes a map which is described as 'Copy from Estate Book'. Comparison of this map with the 1805-25 estate atlas shows the two to be almost identical, and the accompanying book of reference is also derived from the same source. This evidence that the atlas was still employed as a working estate record several decades after it was originally produced is a tribute to Summerfield's skill in producing a useful and durable cartographic record of the earl's estates. This represents an important vote of confidence in the quality and adequacy of the cartography into the mid-nineteenth century, when more and more alternative sources of mapping, such as the tithe surveys and the large-scale plans of the Ordnance Survey, were becoming available. 58 C.K.S. U234 E21, Preface. 59 C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 4. 6° C.K.S. U234 E21, Map number 11. 61 C.K.S. U234 E21, p. 43. 62 C.K.S. U234 E9. 109