Coldrum Revisited and Reviewed

Contributions to the next volume are welcome. See the guidance for contributors and contact Editor Jason Mazzocchi. Also see the guidance for peer review.

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Annual Report

The Lords and Ladies of Tonbridge Castle

Coldrum Revisited and Reviewed

COLDRUM REVISITED AND REVIEWED

PAUL ASHBEE

INTRODUCTION

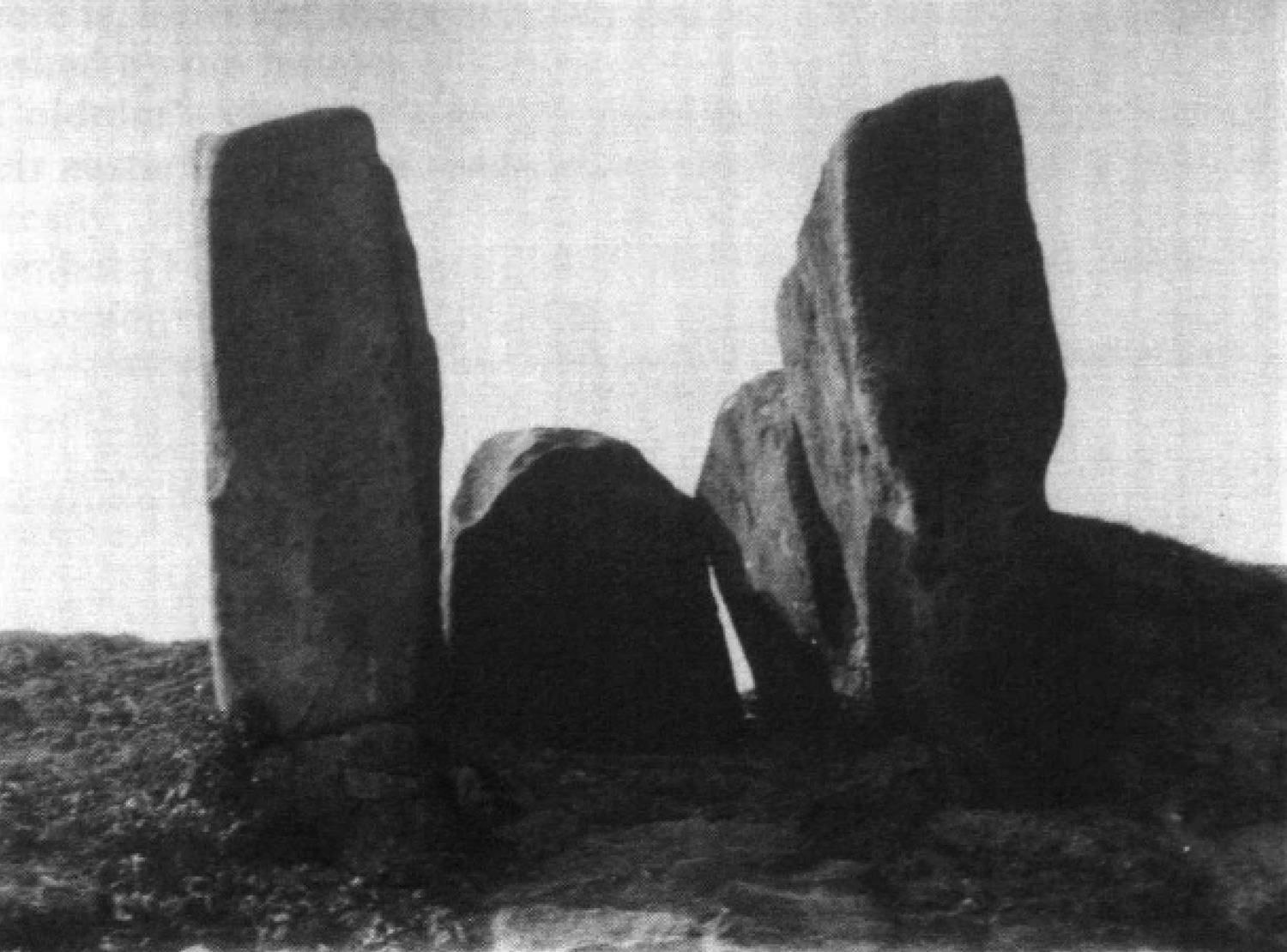

Coldrum (N.G.R. TQ 654606), in Trottiscliffe Parish, is Kent's least

damaged megalithic long barrow. It takes its name from a nearby,

now demolished, farm, Coldrum Lodge. The massive sarsen-stone

chamber, and the low mound, bounded by prostrate slabs, stands

obliquely upon the scarp-edge of a high lynchet (Fig.l). The field

system was already old when Coldrum was built. It is about 100 ft.

(30 m.) in length, the eastern, proximal, chambered, end is 60 ft.

(18 m.) in breadth with a western, distal, of about 40 ft. (12 m.), and

may be the principal, remaining, part of a larger entity. Medieval,

religiously motivated, slighting accounts for its tumbled eastern end.

Some early antiquaries considered Coldrum a circle.

Although apparently isolated, Coldrum may be the lesser of two long

barrows. A huge, spread, mound more than 300 ft. in length and 90 ft. in

breadth, of E-W orientation, lies just under a quarter of a mile to the

north. Its eastern end is almost upon Coldrum's lynchet's northern continuation

(N.G.R. TQ 653610 approx.). There are no signs of sarsen

stones, although some may still be buried. This near-obliteration may

have led to the survival of rather more of Coldrum than might be expected.

In 1910, F.J. Bennett (1913) excavated the upper part of Coldrum's

chamber, finding the skulls and bones of some twenty-two people. In

this he was assisted by E.W. Filkins, who, after the 1914-18 war, dug

to the bottom of the chamber finding soil and further bones (Filkins,

1924; 1928). The bones were examined and described by Sir Arthur

Keith (1913; 1925). Filkins bared the sarsen stones of the kerb and

the monument assumed its present-day appearance.

In 1926, Coldrum, cleared of brushwood and brambles, was vested

in the National Trust as a memorial to Benjamin Harrison, the

Ightham prehistorian and eolith protagonist (Harrison, 1928, 333;

Gaze, 1988, 52). An imported stone bears a plaque describing it as a

circle (Grinsell, 1953,154). Although an Ancient Monument (Jessup,

1948), it is now tree-smothered, defaced, and difficult of access.

1

PAUL ASHBEE

C O L D R U M kJ.o.i^TQ ^ 4 6 o 6

N>--\ M A S S I V E

N

L r U C H I T

*\ V.

'S'SX6.s ^S \ 0

F O I ^ M E e COLD fe UAA

o PCHA fc_b 4«

LA Kl OS

"Vifjl, &A Rk O W

S T & E A M

SOURCES

L Y H C H E T

Q

Q?

?-