Archaeological Investigations at Sandwich Castle

Contributions to the next volume are welcome. See the guidance for contributors and contact Editor Jason Mazzocchi. Also see the guidance for peer review.

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Westgate on Sea - Fashionable Watering-Place: the First Thirty Years

The Exile of two Kentish Royalists during the English Civil War

Archaeological Investigations at Sandwich Castle

I.J. Stewart

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS AT

SANDWICH CASTLE

I. J. STEW ART

with contributions from

M. L. Herdman, J. Iveson and K. Parfitt

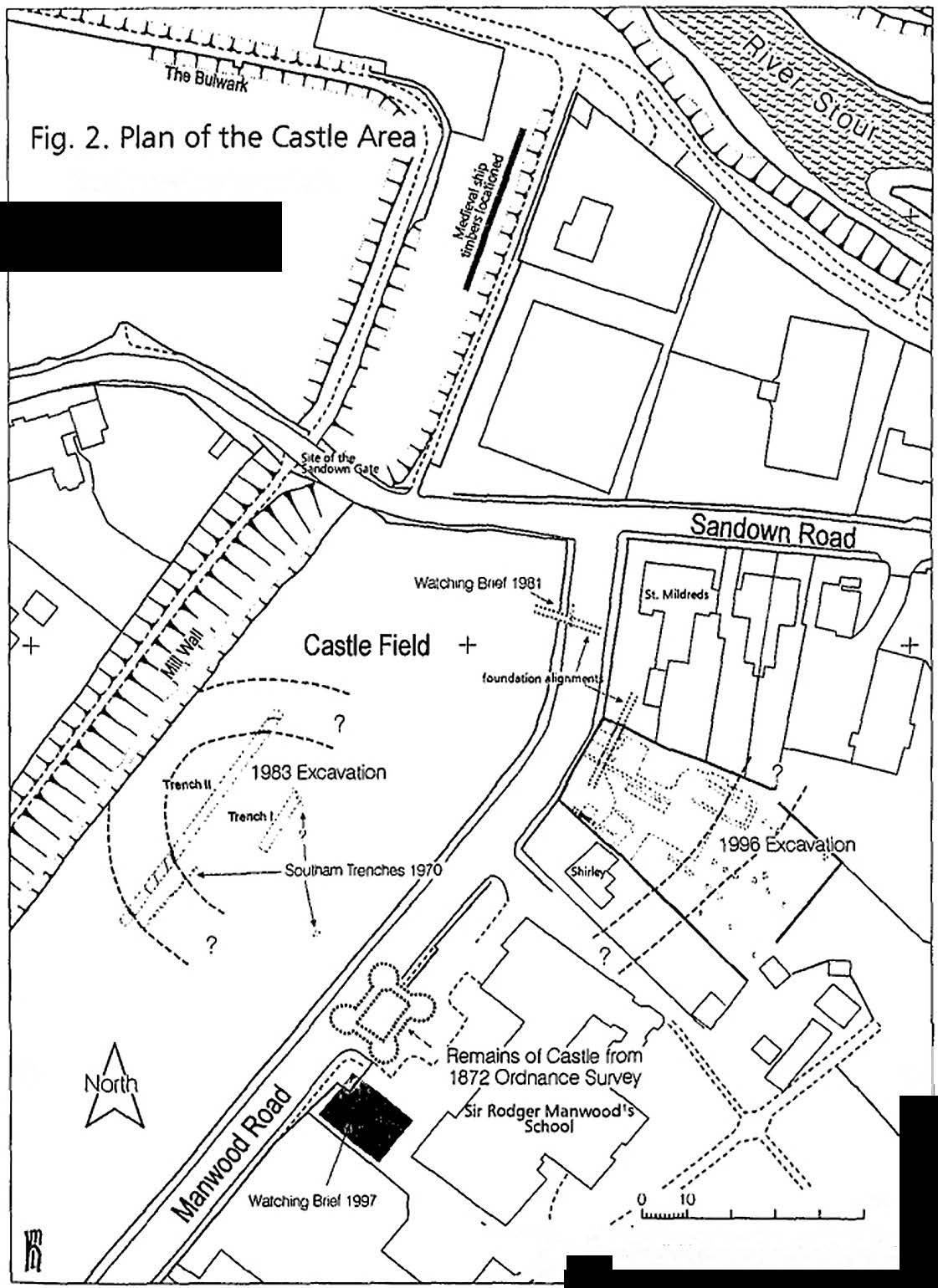

The historic Cinque Port of Sandwich (Fig. 1), with its ancient buildings,

defences and quay on the River Stour, is known from records to

have once had a castle, but today it lacks any obvious remains of such

0 100

ftep,oc:h.1ctd from Ordn.)nce Survey material with the

permjssi0n of The Controller of l-ler Ma;esty's Stationery

Office, C Crown Ccpyr;ght llten