The Origins of the Swale: an Archaeological Interpretation

Contributions to the next volume are welcome. See the guidance for contributors and contact Editor Jason Mazzocchi. Also see the guidance for peer review.

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

The Abortive Plan for Northfleet Naval Dockyard during the Napoleonic Wars

The Construction of the Sevenoaks Railway Tunnel 1863-68

The Origins of the Swale: an Archaeological Interpretation

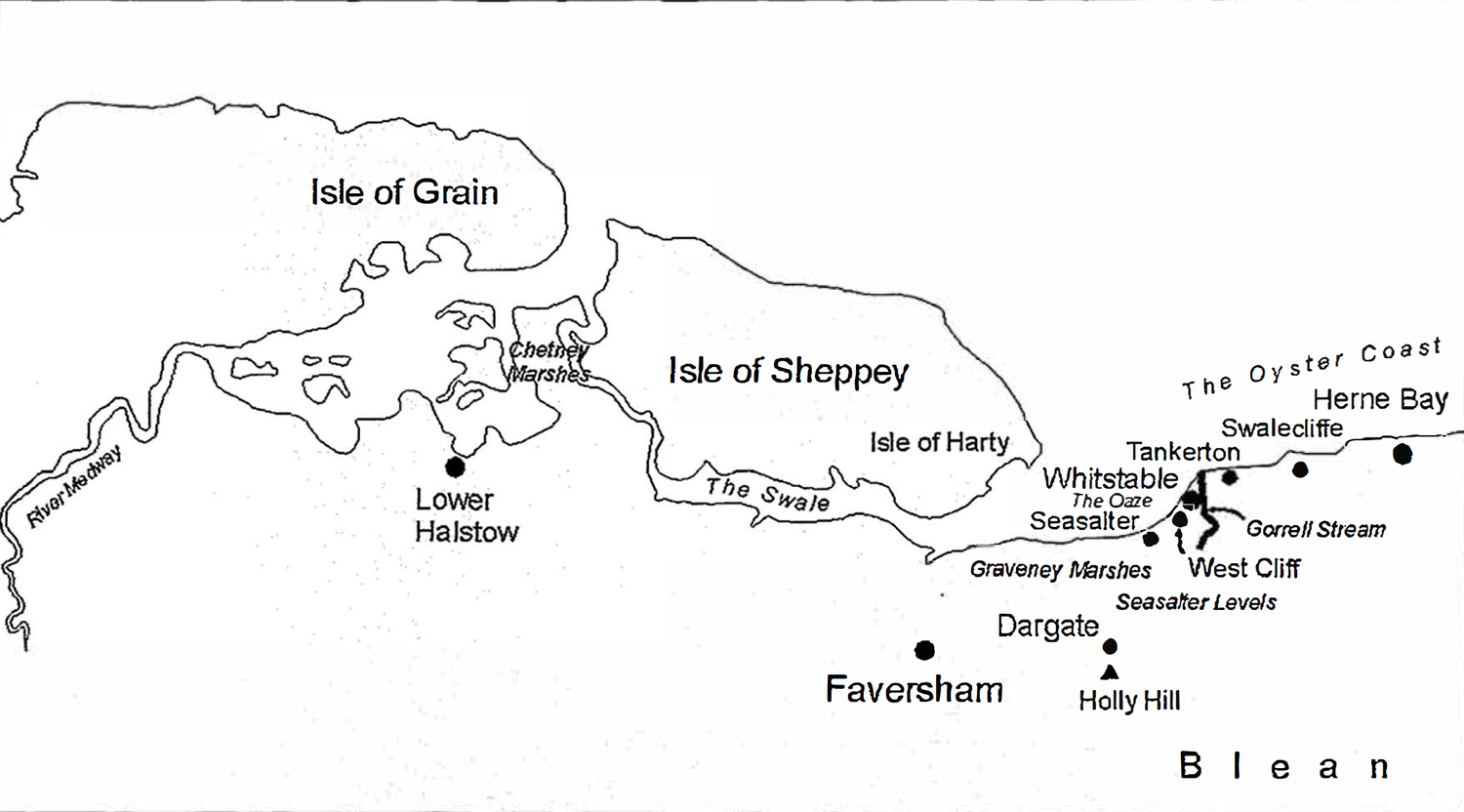

Tim Allen

THE ORIGINS OF THE SW ALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION TIM ALLEN The study focuses on the coastal archaeology and geomorphology of the 'Oyster Coast', and in particular on two cliffed areas, West Cliff and the Tankerton Slopes. The study also addresses some wider issues relating to the origins and development of the Swale and its later relationship with the Lower Medway estuary. It has been widely assumed that West Cliff and the Tankerton Slopes originated as marine-eroded London Clay cliffs. Such an assumption underlies the detailed discussion of such erosion on the North Kent coast in Holmes 1981, 101-5: The average annual loss of land by erosion along the unstabilised parts of the coast from Sheppey to Reculver has been about 1.8m. This figure is deduced from observations and descriptions, of varying accuracy, dating from Roman times to the present day. Accordingly, Tatton-Brown (1977, 212), referring specifically to the Tankerton/Swalecliffe areas, states; 'it should be noted that in c. 1800 BC ... the coastline would have been several miles away to the north as erosion of the London Clay low cliffs is very rapid at this spot'. The subject is discussed in detail by So (1963, 52-108). Many of So's observations make reference to historical accounts of coastal landslips associated with areas of cliff. Partly on this basis, So, like Holmes and Tatton-Brown, assumes that the cliffs which now dominate large parts of the North Kent Coast have their origin in marine erosion and that marine-formed cliffs have dominated the coast for over a thousand years. In support of this, an assertion by Green ( 1961, 21-8) in relation to renewed submergence is cited: 'a reconstruction of the open coastline at about AD 1400 will give us also a reasonably close picture of the same coast as it was a thousand years earlier'. This assumption of a marine eroded cliffed coastline is now disputed and an alternative interpretation is presented below based on an integrated analysis of the area's archaeology and geomorphology. 169 Isle of Grain Isle of Sheppey r coast oy ste Th 8 Herne Bay Swalecliffe,-----;:--- Tankerton 1 • • Whitstable TheOaze Sea salter• f Gorrell Stream Graveney Marshes West Cliff Seasalter Levels Dargate • • Faversham A Holly Hill B I e a n Fig. 1. Map of the Study Area THE ORIGfNS OF THE SW ALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL fNTERPRETATION The primary study area extends east from the Oaze, in the mouth of the Swale, to Hampton, but some features of the Swale itself and the Lower Medway are also examined (Fig. 1). The surface deposits are of variable depth and consist of alluvium, loams, gravels, shingle, brickearth and landslip London Clay, some of which are intermingled (Holmes 1981, 86-7, 90). These overlie approximately 26.5m of London Clay overlying a sequence of Palaeocene Oldhaven sand beds/ Woolwich shell beds/Thanet sands, which in turn overlies Chalk. A low-lying alluvium-covered flat, once inned as a salting and now a golf course, lies immediately north of West Cliff in Whitstable, and is protected from marine inundation by a sea wall. Seasalter, the Seasalter Levels and the Graveney Marshes lie to the west. To the south and east, low-lying alluvium-covered London Clay separates West Cliff from the Tankerton Slopes and is intersected by a small stream, the Gorrell, which disgorges into Whitstable harbour. This area was once marshland known as 'the Outletts', but was drained in the 1790s. It was only after this, and the consequent decline in the incidence of the debilitating 'ague', that the railway (1830) and harbour ( 1832) were built. In succeeding years the coastal settlement known originally as 'Whitstable Street' grew steadily into the town of Whitstable (Hasted 1797; Ward 1944; Bowler 1983). The Tankerton Slopes lie east of the harbour and adjoin the inter-tidal zone. They are protected from erosion by a substantial sea wall, groins and the regular recharging of the foreshore shingle. Swalecliffe, the only unprotected stretch of coast in the area, lies immediately to the east. Here, on the inter-tidal zone, a spit of gravelcovered alluvium overlying London Clay known as 'Long Rock' has produced large quantities of well-preserved Mesolithic flintwork (long blades, tranchet axe heads and Thames picks). This, along with abundant Pleistocene and Holocene lithic and fossil evidence retrieved over many years from the foreshore and the area immediately to the north has led to an interpretation of Swalecliffe as part of a palaeo-channel formed by drainage from the Blean uplands to the south. The channel is now represented by a long, drift-filled irregular valley extending from Honey Hill, near Canterbury, to Swalecliffe. Such an interpretation is also inferred from the presence at Swalecliffe and Hampton, immediately to the east, and also on the Blean itself, of intermingled brickearth and gravel beds (Holmes 1981, 81 ). These gravels were once considered to represent possible evidence of an ancient terrace associated with a postulated more northerly route of the ancient Stour to the Kent coast (Wooldridge and Linton 1955, 127; Coleman 1952, 63-86; Coleman 1954, 52-63). The view that West Cliff and the Tankerton Slopes were originally 171 TIM ALLEN formed by marine erosion assumes, of course, that they were originally coastline features. However, following examination of the stratigraphic, geomorphological and archaeological evidence by the Oyster Coast Fossil Society (OCFS), the Medway Lapidary and Mineral Society (MLMS) and Canterbury Archaeological Trust (CAT), this view has become increasingly untenable. It is proposed that the evidence described below points to a very different origin for the cliffs and suggests an explanation for the abundant Pleistocene and Holocene fossil and cultural materials recovered from the Swalecliffe and the adjacent foreshores. ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE The large body of artefactual and fossil evidence collected from Swalecliffe over many years is described by Richardson ( 1834, 79; 1841, 211), Prestwich (1861, 365, fig. 2), Dewey (1925, 283; 1926, 1432; 1955, 165), Worsfold (1926, 326; 1927, 224) and Burchell ( 1954, 259). The evidence derives from Quaternary sediments exposed by marine erosion in cliff sections and on the foreshore and appears to represent at least two sealed fossiliferous and artefactbearing horizons of late Pleistocene date. The earlier material comprises the skeletal remains of warm-weather species; rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus hemitoechus), elephant (Palaeodon antiquus), hippopotamus and red deer (Cervus elaphus), with flintwork being represented by Acheulian hand-axes and Levalloisian-type flintwork. No stratigraphic link has been established between the lithic and fossil evidence. The later material comprises skeletal material, mostly from cold-weather species; horse (Equus), long-horned cattle (Bos longifrons), woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), hyaena (Crocuta c rocuta) and mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), with flintwork being represented by Thames Valley picks, tranchet axe heads and long blades of the Mesolithic. In addition to these published records, members and associates of the OCFS and MLMS have collected an extensive assemblage of cultural materials, mostly flint artefacts and potsherds, from the Hampton, Swalecliffe, Tankerton, Whitstable and Seasalter foreshores. These include three Lower Palaeolithic hand-axes, five bout coupe-type tools and an extensive assemblage of Mesolithic flint tools. The bout coupe tools were found in close proximity to the we llpreserved semi-articulated skeletal remains of at least three mature aurochs (Bos primigenius). Much of the recently-recovered flintwork is in excellent condition, 172 THE ORIGINS OF THE SW ALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION having suffered only slight or no water-rolling. Notable examples are a small Acheuiian hand-axe, a bout coupe hand-axe and a Mesolithic long blade, all intricately-worked and in near-perfect condition. Also recovered were two examples of Late Neolithic 'shaft-hole' adzes, one made of C ornish greenstone, and one made from the rock of the the Whin Sill in northern England (Wilson 1997, 37-8; Kelly 1964, 225). The recovery of such material from a high-energy tidal environment suggests that the flintwork had only recently been washed out of intact buried land surface(s), or was exposed in situ. Similarly, assemblages of Early and Mid/Late Bronze Age, Early, Mid and Late Iron Age, 'Belgic', Romano-British, Roman and medieval ceramics were recovered, with Late Bronze/Early Iron Age wares ocurring in substantial quantities. Particularly notable is strong evidence for Bronze Age activity at Swalecliffe. For example, an Early Bronze Age 'Beaker' represented by seven sherds and dated to c. 1,800 BC was recovered from the Swalecliffe foreshore (Reedie and Clarke, 1976, 235; Tatton-Brown, 1977, 212), as was a Late Bronze Age hoard containing socketed axes, swords, spearheads, winged axes and founder's metal, currently in the possession of the British Museum (Jessup, 1930, 108). Again, significant amounts of these assemblages were in situ or were recovered in good or excellent condition, precluding a derived or residual status. For example, an unbroken Late Iron Age 'Belgic' coarseware cup was recovered in nearperfect condition from the Seasalter foreshore. Also of significance was the recovery of a slightly abraded gold stater or 'ambiani'. This high-status Gallo-Belgic coin is considered to date to c. 125-100 BC. The recovery from the foreshore of flintwork, ceramic and other archaeological materials in good condition and of such an extensive date-range in an area where marine erosion is held to have removed a considerable depth of the original land surface is clearly anomalous. It is therefore partly on this basis that the conventional interpretation of the coastal geomorphology of the area is challenged. The assemblages described above have been catalogued and, if not otherwise stated, are presently held by the CAT or the OCFS. A summary description of the materials and a discussion of their possible significance within an intertidal environment is provided below The flintwork A total of 66 flint artefacts were collected over a period of eighteen months from the Hampton, Swalecliffe, Tankerton and Seasalter foreshores with the great majority (60) deriving from Seasalter. This 173 TIM ALLEN was probably because the Seasalter foreshore was the most thoroughly examined area and does not necessarily indicate a flintwork concentration in that area. Indeed, when compared with the observations made by Richardson and others over many years (see above), it appears that flintwork distribution may be relatively even along the undisturbed foreshores in this area, with apparent concentration spots marking localised erosion fronts. The increase in flintwork finds from the Seasalter foreshore may therefore coincide with an increased rate of erosion in that area. The pre-Holocene (pre-Mesolithic) flint artefacts are generally stained black/dark brown and occasionally orange, possibly indicating that they were contained over a long period in peat (black/dark brown) or weathered clay and gravel (orange). Whilst most display some degree of abrasion by water-rolling, in some cases abrasion has not occurred. Patination and weather-rinding are usually, but not exclusively, present in the pre-Mesolithic pieces and is not always accompanied by transport damage/abrasion. The majority of the Mesolithic pieces are in fresh condition and are unpatinated. Considering the high-energy environment in which they were found, a significant quantity of both the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic flintwork is remarkably well preserved. As discussed above, the wide date-range and frequently good condition of much of the lithic material within the context of the foreshore environment suggests that at least one buried ancient land surface is, or was very recently, present on the Hampton, Swalecliffe, Tankerton and Seasalter foreshores. It is therefore postulated that the artefacts have only recently been displaced from/ exposed within those contexts on the foreshore by marine erosion. The majority of the flintwork assemblage can be securely dated to the Mesolithic (c. I 0,250 to 6,500 BP) by the presence of diagnostic pieces such as Thames Valley Picks, tranchet axes, pyramid cores and long blades. However, a 200mm long heavily-patinated hand-axe and a severely water-rolled hand-axe are probably the products of a Lower Palaeolithic core culture. The recovery of a small (67mm long) well-worked Acheulian hand-axe in near-perfect condition from the Hampton foreshore suggests the possible presence of a sealed preDevensian horizon or localised pre-Devensian archaeological features in this part of the study area. Similarly, the recovery from the Swalecliffe foreshore of five well-worked cordate flint tools of bout coupe type, conventionally, if tentatively, associated in Britain with the Early-Mid Devensian, suggests the survival there of a horizon dating to that period. This view is supported by the presence among?t the cordate pieces of the 118mm long hand-axe of high quality 1n fresh condition. 174 THE ORIGINS OF THE SWALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION In addition to the above-discussed flintwork, half of a Cornish Greenstone 'shaft-hole' adze in unabraded conditon was found within the shingle on the Tankerton foreshore. As discussed above, this is the second such example to be found in the vicinity. These comparatively rare 'exotic' implements are of interest in suggesting traderelated Neolithic activity in the area. Extensive collections of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic flints from unrecorded sites in the Swalecliffe and Tankerton areas are also held variously by local collectors, East Kent museums and the British Museum. The prehistoric ceramics The prehistoric ceramic material appears to be evenly distributed over the Seasalter, Tankerton and Swalecliffe foreshores. The evidence points to sustained and extensive occupation of large parts of the area during the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age and during the Late Iron Age and early Roman period. However, examples of unabraded wares from other periods indicate other, perhaps more transient, periods of occupation. A large number of the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age and Late Iron Age and 'Belgic' wares are only minimally waterrolled or have suffered no abrasion and are therefore highly diagnostic. Indeed, as previously mentioned, one small 'Belgic' coarseware cup from Seasalter is complete and near perfect. Along with large quantities of later Roman brick and tile (suggesting the presence of buildings), these indicate that the present foreshores were the site of varying degrees of settlement activity from the Bronze Age to the Roman period. The prehistoric ceramic assemblage (collected up to 22 February 1997) consists of 148 pieces comprising: I large rim/part profile of Late Neolithic Peterborough ware; 7 sherds from a single Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age Beaker vessel; I sherd of Late Bronze Age Deveral-Rimbury ware; 131 (a significantly large number) examples of Late Bronze/Iron Age wares (including Late Iron Age wares) I sherd from a rectangular Mid-Late Iron Age briquetage vessel (used in the prehistoric salt industry); 7 examples of 'Belgic' ware. These include two well-preserved corrugated fineware sherds, possibly from pedestal beakers, and a complete and near-perfect small coarseware cup. It should be noted that subsequent sampling has added significantly to the various archaeological assemblages here discussed. 175 TIM ALLEN The Romano-British ceramics Fifty-three sherds of Roman pottery were recovered with dates ranging from the later first to the mid-third century or a little later. As in the case of the prehistoric ceramics, a significant number are in fresh, unabraded condition. Again, distribution of the Roman material is thought to be generally even, with an apparent bias towards the Seasalter foreshore reflecting increased erosion within, and closer examination of that area. It should be noted that Swalecliffe and Hampton and their respective foreshores have been the focus of intense collection activity for over a century and that much Roman ceramic material has been recorded in the area during that period (Branch and Green 1996, 2; Holmes 1981, 91 ). Most of the Romano-British pottery is of local or Kentish manufacture and includes examples of Upchurch-type beakers and dishes (some clearly of late first to early second century date). Thames-side Black Burnished Ware Type 2 (BB2) and Canterbury mortaria are also represented. Several local sand- and grog-tempered coarseware sherds of late second century or later date have been identified, as have two Thames-side BB2-type bead-and-flange dishes dating to the mid third century or later. These are the latest ceramics within the group. Continental imports comprise six sherds of southern and central Gaulish Samian of the mid-first to second centuries and a large (374g) 'hammerhead'-rim sherd in good condition from an Eifelkeramik mortarium. Eleven fragments of Roman brick and twenty-two fragments of Roman tile (tegulae) including one very fresh with maker's mark were also recovered. This represents only a small sample of the many Roman brick and tile fragments present on the Seasalter and Swalecliffe foreshores. The Anglo-Saxon and later ceramics Within this assemblage a clear distribution concentration was observed on the Seasalter foreshore with 98% of the material deriving from that area. The remainder comprises Anglo-Saxon sherds with little abrasion evident and severely abraded post-medieval sherds. All of the latter derived from the Swalecliffe foreshore, where no significant quantities of medieval ceramic material have been recorded by previous collectors. The Anglo-Saxon and medieval assemblage is of varying condition. Most sherds are worn to some degree but there are several large and fairly unworn sherds amongst the earliest material (early-mid eighth 176 THE ORIGINS OF THE SWALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETAT[ON century). The thirteenth-century material (locally manufactured Tyler Hill ware) is generally fairly fresh and in some cases completely unworn whereas later material (sixteenth to seventeenth century) is extremely water-rolled. In the later material, the sea in association with the anaerobic chemistry of the foreshore ooze appears to have attacked and chemically altered most of the glazed pottery, reducing the original clear lead glaze to shiny dark grey sub-metallic lead sulphide. The usually shiny hard brown salt glaze found on postmedieval German stonewares was in one case been completely removed by chemical action. This suggests that much of the earlier and less robust material had only recently been washed out of its containing medium which was therefore relatively stable. In contrast, the severely abraded and eroded condition of the hard-glazed postmedieval sherds suggests a derived status within the foreshore clays and gravels. The Anglo-Saxon and medieval assemblage consists of 252 pieces comprising: 1 rim sherd of Anglo-Saxon Ipswich ware (Fabric EMS6). Date range (max.) c. 725-850; 1 rim sherd of possibly Anglo-Saxon sandy ware (Fabric ?EMS/MLS 1,). Date c. ?450-850; 1 example of Late Saxon (?N. French) or early medieval profuse shellfilled ware (Fabric LS4 or EM2 variant). Date c. ?850-1050/1050-1225; 159 examples, including 60 rim sherds, of Canterbury early medieval sandy ware (Fabric EM!). Date range (max.): c. 1050-1225; 12 examples, including 6 rims of early medieval shelly ware (little/no sand) (Fabric EM2). Date c. I 050-1225; 15 examples, including 3 rims, of early medieval sandy shelly ware (Fabric EM3A). Date c. 1075-1225; 2 examples of early medieval unidentified wares (EM I 00). Date 11 th- I 3th centuries; 2 examples of early medieval North France/Flanders grey sandy ware (Fabric EM7). Date c. 1125-1175; 2 examples of early medieval North France/Flanders fine grey sandy ware (Fabric EM18). Date c. 1125-1175; 2 examples of early medieval North France/Flanders fine sandy ware with shell (Fabric EM25). Date c. 1125-1175; 3 rim sherds of Canterbury shell-dusted sandy ware (Fabric EM.MI). Date c . 1175-1250; 48 examples, including 4 rims, of Tyler Hill ware (Fabric MI). Date c. 1175/ 1200-1525/50; 1 rim sherd of Late Tyler Hill ware (Fabric LM 1 ). Date c. 1375-1525/50; 1 example of Canterbury fine earthenware (Fabric LM2). Date c. 1475- 1550; 2 examples of German Frechen stoneware (Fabric PMS). Date c. 1525-1750. 177 TIM ALLEN Apart from the sparse but well-preserved Anglo-Saxon finds, the earliest medieval pottery to occur along the Oyster Coast is Canterbury- type early medieval sandy ware typical of the period c. 1075- 1125, although some larger beaded rims are more typical of the period c. 1150-1175. This is the most common fabric from Anglo-Norman contexts in and around Canterbury, some 9.5 km. to the south, and is also the commonest medieval fabric from the Oyster Coast area, comprising 64 per cent of the pottery assemblage here discussed. Locallymanufactured Tyler Hill ware is the most common 'high' medieval fabric present (19 per cent). This dates to the period c. 1200-1350. Late medieval fabrics are rare in the collection and all examples are severely water-rolled. There are only two sherds (including an LMl bowl rim) for the fifteenth/early sixteenth-century period and only one vessel (part of a German stoneware jug of c. 1550-1625) for the late sixteenth/early seventeenth-century period. Interpretation Overall, the evidence of the flintwork and pottery suggests sporadic but intensive periods of occupation on dry and habitable flatlands north of West Cliff (now the Seasalter foreshore) throughout the Holocene up to about AD 1300. The ceramic evidence suggests sustained human activity during the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age, the Late Iron Age and Roman periods. Much-decreased activity is suggested for the eighth or ninth centuries AD with more intense activity resuming from the later eleventh century onwards. Activity as gauged by potsherd quantities was most intense during the years c. I 075- 1175/1200, followed by a decrease in the thirteenth or possibly the early fourteenth century, probably no later than c. I 325. Thereafter, a sudden drop in the amount of pottery being used or discarded _is evident. The quantity of numismatic evidence also declines significantly at this time (Harrison and Wren 1995). Interestingly, the first recorded Seasalter sea defence (a substantial earth bank) was built in 1325 (L.C.1887, i, 139-49; Dugdale 1772, 20). It is therefore postulated that between c. 1250 and 1325 a previously intensely-occupied land surface was abandoned in the face of marine encroachment. On the basis of the above-presented archaeological evidence it appears that West Cliff has not been subject to marine erosion from the Mesolithic onwards and, given the general rise in Holocene sea levels, had probably never been subject to marine erosion throughout the Postglacial period. The evidence also appears to preclude the poss_ibility of substantial freshwater erosion during the Holocene d, as discussed below, this is perhaps of greater interpretive signif1c- 178 THE ORIGINS OF THE SWALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION ance. It is also postulated that, as Devensian sea levels are considered to have been up to 11 Orn lower than at present (Sparks and West 1972, figs 5.18, 5.23), West Cliff is a pre-Devensian feature. As discussed above, So (1963) argues that to the east of West Cliff, the low London Clay cliffs have their origin in marine erosion, although he acknowledges that this is based partly on recent historical accounts of major landslips. He goes on to argue (1963, 52-3) that witnessed records of landslip are merely recent examples of a longestablished and continual process: As recording is generally made immediately or shortly after the event, and largely by people staying nearby, there is no wonder that reports made are likely to be more towards recent times, as early barren periods are related to periods of sparse population. However, intact remains of sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century copperas works discovered on the foreshore at Tankerton immediately adjacent to the slopes (Allen 1999, 2-3; Allen, Pike and Cotterill, forthcoming), along with related documentary evidence, appear to demonstrate beyond doubt that the Tankerton Slopes could not have been exposed to marine erosion until the late post medieval/ modern period: In 1639 it was said that the first works in the Whitstable district had been erected fifty years before. Another had been set up about 1610, but both had since disappeared with the encroachment of the sea. (PRO E 134/15 Chas I, in Chalkin 1965, 154-5) It should also be noted that rotational slippage occurs in London Clay when it is exposed to marine erosion, as can be seen on the north coast of Sheppey, and that there is no sign of such slippage on the Tankerton Slopes or West Cliff. Further east, on the Swalecliffe and Hampton foreshores, a rather different picture emerges. Here, periods of sustained human activity during the Lower Palaeolithic, the early Upper Palaeolithic and the Mesolithic are indicated by the recovery over many years of significant quantities of diagnostic flintwork in good condition as described above. Decreased activity during the Neolithic is perhaps suggested by the smaller amounts of cultural materials from that period but the presence of Early Bronze Age, Mid-Late Iron Age, Late Iron Age ('Belgic') and Romano-British ceramics, some showing no sign of wear, indicates that occupation activity continued up to the Late Roman/Early Anglo-Saxon period. The absence of any significant cultural materials post-dating this period may suggest that the area 179 TIM ALLEN was abandoned because of marine encroachment during that period. It is therefore proposed that the flats at Swalecliffe were probably rendered unoccupiable by marine erosion from the Late Roman/Early Anglo-Saxon period onwards. Again, as in the case of West Cliff, the archaeological evidence points to a pre-Holocene, and probably pre-Devensian origin for the Tankerton Slopes, with the recovery of apparently recently in situ Lower Palaeolithic, Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic flintwork offering strong support for this hypothesis. Clearly, the view that West Cliff and the Tankerton Slopes first formed as a result of marine or river erosion during the Holocene is incompatible with this evidence and therefore another, earlier origin must be sought. GEOMORPHOLOGY AND STRATIFICATION An insight into the possible origin of the two cliffs was gained during recent archaeologically-monitored test trenching in advance of proposed coastal defence works carried out by Canterbury City Council. This work exposed a partially-intact, palaeo-environmental sequence of felted peat, gravels, clays, sands and silts along the entire length of the Tankerton foreshore. However, in the eastern part, some 740m west of Swalecliffe, the sequence increased in complexity. Here the gravels, clays, sand and silts were seen to be punctuated by three substantial peat deposits containing seeds and large quantities of wood in the form of well-preserved twigs and branches. The peats had apparently formed on the margin of a deep linear feature lying below and some 1 Orn north of the Tankerton Slopes (coastal erosion has subsequently exposed two further overlying peat deposits). This complex sequence of deposits is suggestive of alternating woodlanddominated terrestrial and marine environments but is not considered to be of any great age. Beetles, including terrestrial forms, along with fragments of oyster and mussel shell and the remains of small seaweed species were identified during a preliminary examination of a small peat sample from the sequence, as were freshwater/low salinity mollusca and marsh-plant seeds (pers. comm. Dr E. P. Allison). It is possible that similar, more deeply buried peaty deposits may be the source of the flintwork and fossils recovered from this area. Given that the Tankerton Slopes and West Cliff were not formed as a result of marine erosion, the simplest alternative interpretation is that they once represented part of the southern valley side of the Swale, with which both are aligned. This in turns raises important questions as to the origin of the Swale, which at present forms an 180 THE ORIGINS OF THE SW ALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION eastern arm of the Lower Medway. The implications of this proposal are far-reaching and some are discussed below. DISCUSSION The above-presented evidence suggests that the Tankerton Slopes and West Cliff, along with the intermingled brickearth and gravel beds on the northern Blean as discussed by Holmes (see above) can be linked with a terrace system associated with the Swale. This raises complex questions about the overall extent and development of the ancient Swale during the Late Quaternary and its later relationship with the Lower Medway and the associated non-alluvial islands such as Sheppey and Grain. It has been proposed that, during the earlier Quaternary, before they were established in their present channels, the Medway and the Thames took a more northerly route than at present, with both flowing into what is now south Essex (Bridgland 1994, 8, 292). It is also proposed that during the Early Holocene, perhaps 8,500 - 7,500 BC, the coastline was approximately 50km further east than at present and that a land bridge still linked Sheppey with the mainland (Fig. 2), separating the Medway from the Swale. ---. ·-. Major rivers (c.8500-7500 BC) Mesolothic coasUlne Modem coastline The Blean __ ..... .,. .. '\ I I I l o 25m. I -f- ,-- ) I Fig. 2. The Mesolithic Coastline c. 8500-7500 BC (after Wilkinson and Murphy 1995) 181 TIM ALLEN This points to the presence of a continuous Blean-like London Clay upland incorporating what is now the Isles of Sheppey, Grain and the Hundred of Hoo now lying north of the Swale. During this period, the Swale valley, without the alluvium which later accumulated within it (presumably when it became tidal), and before it became part of the Lower Medway, appears to have had the form of an elongated oval basin some 6km wide and I 0.5 km long, with bottlenecks consisting of narrow channels in the London Clay at either end, one in the vicinity of the Chetney Marshes, the other in the vicinity of the Isle of Harty. It should be noted that drainage into the Swale from the Blean upland in the area of Holly Hill, Dargate, at which the Blean reaches its highest point ( OD I 08m), appears to have caused considerable erosion, along with local re-deposition of eroded material to form what is now the Graveney and Seasalter marshes, which adjoin the Swale to the south (Holmes 1981, 89). Similarly, the survival of an isolated patch of Head or River Terrace Gravels on Holly Hill suggests that most of the gravels conventionally associated with terrace deposits were removed during the course of this erosion, which appears to have left outcrops of partly-eroded London Clay in the form ofDenly Hill and Horse Hill protruding through the alluvium of the marshes (Fig. 3). Recent work conducted on the Seasalter Levels by the Centre for Quaternary Studies, Royal Holloway, suggests that much of the Seasalter Levels consists of an alluvium-filled bay, the London Clay-dominated alluvium having washed down from the Blean as a result of the above-described erosion (Williams, 1999). ! [100m. 0 NNW 0 5kms. Horlzontol ocolo The Blean Hoity Hill ssE Fig. 3. Schematic Profile showing the Blean, the Swale and Sheppey (vertical exaggeration, roughly 17 times) 182 THE ORIGINS OF THE SWALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION During this work, alluvium, almost certainly downwash from the Blean, was shown to be at least Sm in depth at two widely separated points on the marshes. London Clay re-deposited as alluvium is also apparent on higher ground near Dargate, just north of Holly Hill. Special interest attaches to the flat tract of very clayey brickearth that extends northward of Dargate Common. Topographically it resembles an alluvial flat with a clearly defined limit all along its north-eastern and northern side. The material is mostly a stiff ochreous and grey-weathering clay, very similar to undisturbed London Clay, from which on the south it becomes lithologically inseparable in the field when traced laterally ... Surrounding features suggest that this drift resulted from the silting up of a muddy lake, filled with down wash from the London Clay and impounded behind a low ridge north-east of Dargate House. (Holmes 1981, 89) Taken as a whole, the above suggests that a series of lagoon-like flu vial features, of which the Swale was one, may have occupied the stepped relief of the northern Blean during the Late Quaternary and Early Holocene. Overall, the evidence suggests that the Tankerton Slopes and West Cliff are the remains of a Swale terrace which survived because they lie too far east to have been eroded by high-energy drainage from the higher parts of the Blean in the Dargate area. Marine erosion, which is conventionally held to be the process by which they originally formed, can be shown on the basis of archaeological evidence to have played no part in their formation. It is therefore proposed that the cliffs represent the southern valley side of the ancient Swale, and that the rich palaeontological and archaeological resource associated with Seasalter and Tankerton are associated with Swale terrace deposits or, in the case of Swalecliffe and Hampton, with tributaries of the Swale which now survive as a drift-filled valleys. The pre and early/mid Devensian age of some of the flint implements and fossil bones recovered from the Swalecliffe and Hampton foreshores in turn suggests that occupation in the Swale valley bottom pre-dates the last Ice Age. It may also be postulated that, if the above interpretation is correct, the entire stepped relief extending northward and downward from the Blean upland to the present coastline comprises part of the Swale terrace system. RESEARCH POTENTIAL In the above archaeologically-based re-interpretation it is suggested that the Swale is an ancient river valley, later subsumed as an eastern 183 TIM ALLEN arm of the Medway. The consequences of this in terms of the area's geomorphology and archaeology remain to be explored. However, using the above-described method of archaeologically-based analysis, it now appears possible to measure the rate of marine incursion along the flood plain of the Swale and elsewhere in order to draw conclusions which are of both archaeological and geomorphological interest. For example, evidence may be advanced to suggest that the Roman shorefort of Regulbium (Reculver) was built to guard the eastern entrance to the Swale, thus protecting the wealthy villas of the Medway Valley, as well as protecting the northern entrance of the Wantsum Channel. Similarly, recent work conducted by Royal Holloway at Lower Halstow, to the west of the Swale, has exposed an intact and substantial 'fringe' of stratified archaeological deposits, including an extensive buried Mesolithic occupation horizon, abutting a steep London Clay bank. An overlying, and therefore later, horizon containing Roman period material suggests that occupation of this part of the Lower Medway flats continued well into the Roman period. It is thought that further work will provide precise dates as to when the flats were eventually abandoned. It is also contended that the above-described work illustrates the importance of archaeological evidence as an indicator of environmental change. Most readers of this article will find much archaeological evidence to be of intrinsic interest but, as part of a crossdisciplinary approach, it can also be seen to provide a powerful tool for geomorphological analysis. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Mark Harrison, Chris Milbank, Dr Chris Green, John Cotter and Nigel Macpherson-Grant for their help and advice in compiling the above report. BIBLIOGRAPHY Allen, T., 'Copperas, the first major chemical industry in England'. Industrial Archaeology News, 108, Spring 1999. Allen, T., N. Branch, J. Cotter, C. Green, L. Harrison, M. Harrison, N. Macpherson-Grant, A. Savage and T. Wilson, 1996, A Preliminary Archaeological Assessment in Advance of Proposed Coastal Works in Tankerton Bay (unpublished CAT report). Allen, T., M. Cotterill and G. Pyke, 'Copperas: an account of the Whit stable c?pperas works and the first major chemical industry in England'. Industrzal Archaeological Review, forthcoming, 2001. 184 THE ORIGINS OF THE SWALE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION Bowler, E., 1983, A Survey of the Works of the Sewer Commission, Studies in Modern Kentish History. Branch, N. and C. Green, 1996, Swalecliffe Project, Kent Palaeoenvironmental Assessment (unpublished ArchaeoScape report). Bridgland, D. R., 1994, Quaternary of the Thames. Burchell, J. P. T., 1954, 'Loessic deposits in the Fifty-foot Terrace postdating the main coombe rock of Baker's Hole, Northfleet, Kent', Proc. Geol. Assoc., Vol. 65, 256-61. Chalkin, C. W., 1965, Seventeenth Century Kent. Coleman, A., 1952, 'Some aspects of the development of the lower Stour, Kent', Proc. Geol. Assoc., Vol. 63. Coleman, A., I 954, 'The relief and drainage evolution of the Blean', Proc. Geol. Assoc., Vol. 65. Dewey, H., 1925, 'The Palaeolithic gravels of Slurry, Kent', Proc. Geol. Assoc., Vol. 36, 278-84. Dewey, H., 1926. 'The river gravels of the South of England, their relationship to Palaeolithic Man and to the glacial period', C. R. 13th Congr. lnt. Geof., 1922, 1429-1446. Dewey, H., 1955, 'Frederick H. Worsfold', in Annual Report of the Council, Proc. Geol. Assoc., Vol. 66, 165-6. Dugdale, Sir W ., 1772, A History of lmbanking and Draining ... Evans, J. G., 1978, The Environment of Early Man in the British Isles. Green, C., 196 I, 'East Anglian Coastline Levels since Roman Times', Antiquity, XXXV. Harrison, M. and C. Wren, The Kent Oyster Coast Environmental Survey Project (unpublished O.C.F.S. report). Hasted, E., 1797-180 I, Historical and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent. Holmes, S. C. A., 1981, Geology of the country around Faversham (Geological Survey of Great Britain). Jessup, R. F., 1930, The Archaeology of Kent, 108. Kelly, D. B., I 964, 'Maidstone Museum: Implement Petrology Survey', Archaeologia Cantiana, lxxix, 207-226. King, C. A. M., 1981, The Stratification of the London Clay and Associated Deposits, London. Literae Cantuarienses, 1887 (Rolls Series). Lowe, J. J. and N. P. Branch, 1996, 'Chatham Dockyards Palaeoenvironmental Assessment' (unpublished ArchaeoScape Consulting Report). Prestwich, J., 1861, 'Notes on some further discoveries of flint implements in beds of post-Pliocene gravel and clay; with a few suggestions for search elsewhere', Q. J. Geol. Soc., London, Vol. 11, I I 0-12. Public Records Office, Exchequer 134/15, Charles I, East 7. Reedie, K. and D. L. Clarke, 1976, 'Beaker' (under Archaeological Notes from the Royal Museum, Canterbury), Archaeologia Cantiana, xcii, 235. Richardson, W., 1834, 'A short notice of the coast section from Whitstable in Kent to the North Foreland in the same county', Proc. Geol. Soc. London, Vol. 2 (1838), 78-9. 185 TIM ALLEN Richardson, W., I 841, 'Observations on the locality of the Hyracotherium', Trans. Geol. Soc. London, Series 2, Vol. 6, 211-4. Rose, J., C. Turner, G. Coope, M. Bryan, 1980, 'Channel changes in a lowland river catchment over the last 13,000 years', in Timescales in Geomorphology. So, K. L., 1963, Some Aspects of the Form and Origin of the Coastal Features of North-East Kent, unpublished doctoral thesis, University of London. Sparks, B. W. and R. G. West, 1972, The Ice Age in Britain. Tatton-Brown, T., 1977, 'Beaker from Swalecliffe', Archaeologia Cantiana, xciii, 212. Wilkinson, T. J. and P. L. Murphy, 1995, The archaeology of the Essex coast, Volume I, the Hui/bridge Survey, E. Anglian Archaeological Report 71, Chelmsford. Williams, A., 1999, A Reconstruction of the Vegetational History of Seasalter, Kent,' using Palynological Techniques (an unpublished B .Sc dissertation, Geography/Archaeology, Royal Holloway, University of London). Wilson, T., 1999, 'Scattered flints: lithic analyis during I 996-97', Canterbury's Archaeology, 37-38. Ward, G., 1944, 'The Origins of Whitstable', Archaeologia Cantiana, Jvii, 51-5. Woolridge, S. W. and D. L. Linton, I 955, Structure, Surface and Drainage in South-East England. Worsfold, F. H., 1926, 'An examination of the contents of the brick-earths and gravels ofTankerton Bay, Swalecliffe, Kent', Proc. Geol. Assoc., Vol. 37, 326-39. Worsfold, F. H., 1927, 'Observations on the provenance of the Thames Valley Pick, Swalecliffe, Kent', Proc. Prehist. Soc. East Anglia, Vol. 5 (for 1926), 224-3 I. 186