Archaeological Investigations at Castle Road Sittingbourne

Contributions to the next volume are welcome. See the guidance for contributors and contact Editor Jason Mazzocchi. Also see the guidance for peer review.

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

The Kilwardby Survey of 1273-4: the Demesne Manors of the Archbishop of Canterbury in the later 13th Century

Brotherhood and Confraternity at Canterbury Cathedral Priory in the 15th Century: the Evidence of John Stone's Chronicle

Archaeological Investigations at Castle Road Sittingbourne

Jon Sygrave

Archaeological Investigations at Castle Road, Sittingbourne

jon sygrave

with contributions by Lucy Allot, Luke Barber, David Dunkin, Lucy Sibun and Charlotte Thompson

Archaeology South-East (ASE), a division of University College London Field Archaeology Unit (UCLFAU), were commissioned by CgMs Consulting Ltd to carry out a Stage 2 Archaeological Excavation on Plot L1, Castle Road, Sittingbourne, Kent (NGR TQ 592020 164867) between 13-28 March 2006. The Stage 2 Excavation was informed by the preceding Desk Based Assessment (Sparey-Green 2000) and Stage 1 Archaeological Evaluation (OA 2005). This article represents a summary of the results of the Archaeological Evaluation and Excavation, the archive of which is to be deposited at Sittingbourne Museum (site code CRS06).

The site covered an area measuring 1,796m² and was bounded by Castle Road to the east, Gas Road to the south, residential property to the west and Plot L2 to the north (Fig. 1). The site lay c.200m to the east of Milton Creek, above the flood plain, where the modern ground surface varied from 7.60m od in the east to 7.25m in the north-west. A large deposit of twentieth-century fire debris, ‘town ash’, was recorded in the north-west of the site surviving to 7.13m od. The site was situated on Thanet Bed (sand) deposits, as shown by the British Geological Survey Sheet 272, which were observed between 6.58m od in the north west and 7.08m in the south. In the east of the site the underlying natural sand was sealed by Brickearth deposits observed between 7.24m od in the east and 6.99m in the centre. The distribution of Brickearth deposits is known to have been affected by brick production on the site.

Archaeological Background

Archaeological features recorded on the site relate to the later prehistoric, Romano-British and post-medieval periods; a brief background of these periods is presented below.

The later prehistoric period in Southern Britain is typified by the gradual formalising of the landscape during a period of agricultural revolution (Yates 2004). Landscape features, such as enclosure ditches, and smaller features, such as pits and postholes, from the later prehistoric have been recorded in the vicinity of the site during investigations conducted by Canterbury Archaeological Trust (CAT) in 1997/8, to the north of the site on Plot K (CAT 1998), and on the adjacent Plot L2, Castle Road in 2003 (CAT 2003).

The transition between the later prehistoric and Romano-British landscapes was gradual, the major differences being the development of roads such as nearby Watling Street and the advent of villas. The earliest Roman sites in the area are thought to have been a series of forts along the north Kentish coast. Detsicas has postulated that one such fort was located on Milton Creek which led to the development of the, as yet undiscovered, settlement of Durolevum, the duro- element of the name coming from the presence of the fort (1983, 81). Archaeological investigations undertaken by the Swale Archaeological Survey suggest that the area to the north of Watling Street, between Sittingbourne and Faversham, was an early example of a series of planned villa estates, laid out for Roman colonists from the first century ad (Denison 2000). Evidence of first-century Romano-British enclosure ditches, pits and postholes was recorded during the adjacent CAT excavations at Plot L2, Castle Road in 2003. Evidence of Roman burials, and a possible cemetery, has also been recorded in the vicinity of the site, notably by the local Antiquarian George Payne, during the period of brickearth extraction in the area, which began in the mid nineteenth century.

The site was used as a brickfield from the mid nineteenth to mid twentieth centuries. To the east of the site large quarries were excavated and long timber drying sheds were situated on the site (local resident, pers. comm.). After the Second World War debris (‘town ash’) from bomb damage in London was brought to near the site and sifted for use in the construction industry (local resident, pers. comm.).

Period Descriptions

Early Prehistoric

Mineralised animal bone was collected from the underlying Thanet Bed sand deposit. The material is thought to be of a generally bovoid nature and showed wear from fluvial abrasion suggesting secondary deposition via geological action.

Later Prehistoric

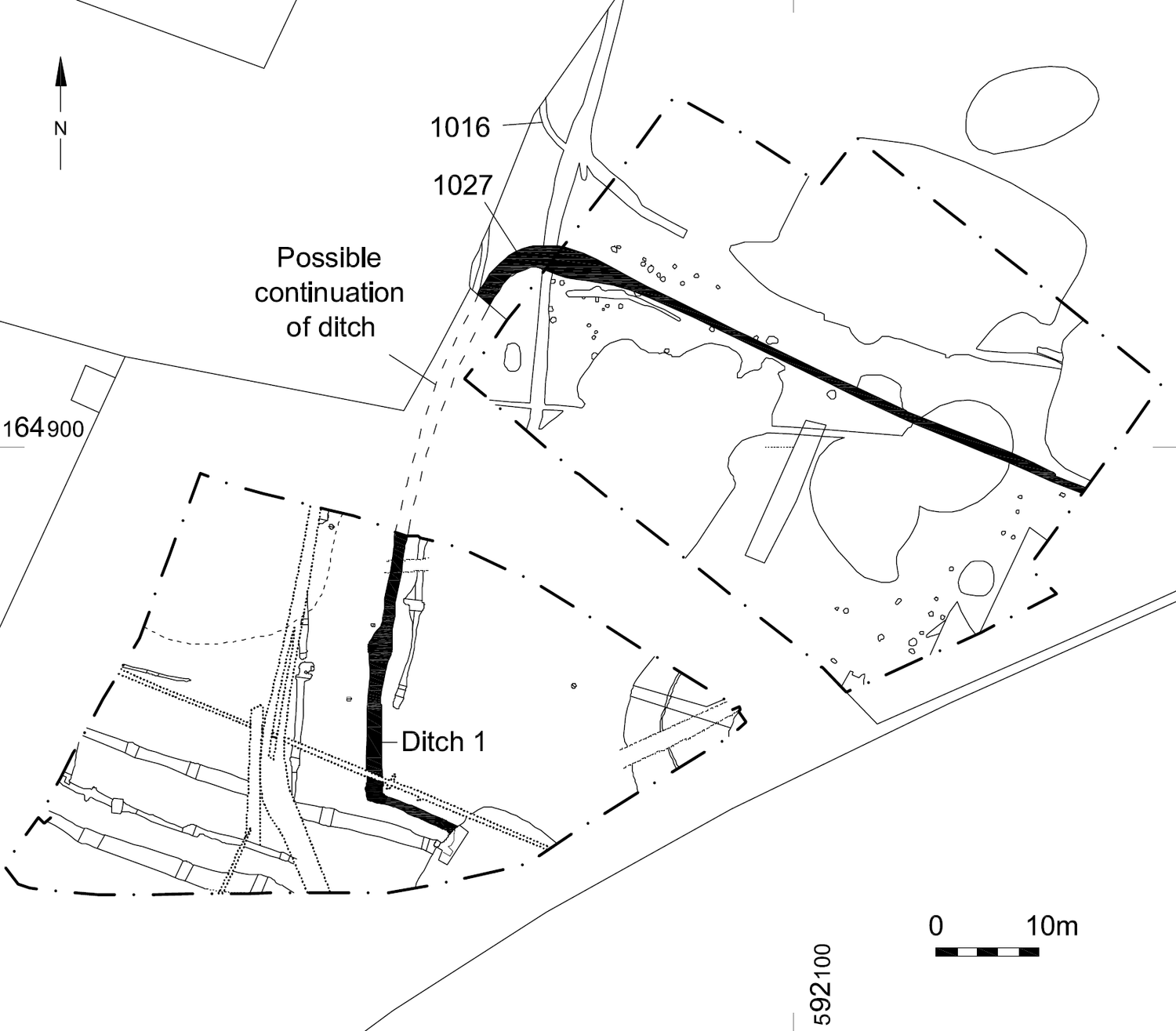

A north-south ditch which turned to run east-west (Ditch 1) was recorded on the site (Fig. 2), truncated at its eastern extent by Romano-British Pit 2 (see below). Ditch 1 contained sherds of pottery from a glauconite-tempered vessel, whose highly polished exterior and dense glauconite tempering suggest a later Iron Age date. Ditch 1 also contained a small quantity of worked flint including rough waste pieces dated from the later Bronze Age to Iron Age, a small amount of burnt clay and a clay weight. A small number of animal bones were recovered including those from mature cattle, mature and juvenile sheep and a small mammal. An environmental sample taken from the ditch fill noted a small number of wheat, barley and oat/brome grains and few wild/weed seeds. The environmental assemblage was of a similar nature to those of an Iron Age date recorded from the CAT investigation (CAT 2003) at Plot L2, Castle Road and can be interpreted as ‘background noise’ within the feature (Fig. 3).

An east-west ditch (Ditch 2) parallel and to the south of Ditch 1 was recorded, truncated at its eastern extent by Romano-British Pit 2. The only dating evidence for the ditch was a piece of medieval/post-medieval peg tile recorded on the surface of the feature and interpreted as intrusive. The ditch has been interpreted as late prehistoric in date due to its relationship with early Romano-British Pit 2 and its similar alignment to Ditch 1. The only other finds were a small assemblage of animal bone including two cattle long bone fragments and a single fragment of sheep radius from mature individuals. An environmental sample taken from the ditch contained two indeterminate grains and one charred Galium sp. seed and was generally comparable to the sample taken from Ditch 1. The presence of uncharred seeds in the environmental assemblage suggests disturbance.

An east-west ditch (Ditch 3) was recorded at the southern extent paral-lel to Ditch 2. The ditch contained no dating evidence and only a small assemblage of animal bones including five fragments of cattle bone and a single small mammal fragment. An environmental sample taken from the ditch contained no macro plant remains.

A pit (Pit 1) was recorded at the northern extent truncating one of two small pits/postholes. The pit contained pottery sherds tempered with flint and glauconite of Iron Age date and a single fragment of small mammal bone. An environmental sample taken from the pit produced a small assemblage of one barley grain, one indeterminate charred cereal grain and a mineralised seed fragment. A single piece of residual worked flint, possibly a soft hammer fragment with a hinge fracture, of a possible Neolithic date, was recovered from the separate small pit/posthole.

Romano-British

A large quarry pit (Pit 2) was recorded at the south-eastern extent, which truncated Ditches 1 and 2. The pit contained a small assemblage of early Roman pottery sherds including a flint-tempered bead-rimmed jar, a possible piece of Hoo Island white-slipped ware and a small piece of Roman tile. A small amount of medieval/post-medieval pegtile was recorded in the upper fill of the feature and interpreted as intrusive. Only three fragments of bone were recovered from the pit; one cattle longbone fragment, one sheep molar and a humerus identified as dog.

A shallow north-south ditch (Ditch 4) was recorded extending from the northern baulk to the centre of the site. The ditch contained a small assemblage of early Roman pottery including reduced fineware and grog-tempered sherds, including one Patchgrove grog-tempered sherd, a possible piece of later Bronze Age perforated clay slab and a small quantity of fire cracked flint. Only two pieces of animal bone were recovered; one fragment of juvenile sheep humerous and a dog metatarsal.

A shallow north-south ditch (Ditch 5) was recorded running parallel, and to the west of Ditch 4. The ditch was made up of two sections, butt-ending less than 0.5m apart, which have been interpreted as component parts of a single ditch which, with Ditch 4, may have formed a drove way or similar landscape feature. Of the 100 early Roman pottery sherds recovered from the ditch over half are from a large wheel-made necked bowl or jar made in a sand-tempered fabric. It is similar to the S-profile bowls from the Upchurch/Thameside kilns, particularly 4A2.10 (Monaghan 1987, 114). On the shoulder are groups of angled burnished lines which are a common decoration on these S-profile bowls. The context also contains a number of flint-tempered vessels such as a hand-made flint-tempered jar with grooves or deep combed decoration; a beaded rim in the same context could belong to the same vessel. This rim appears to have pitch on the lip which, as well as the temper and form, points to a pre-Flavian date. Another sparse flint-tempered jar from this context has an upright beaded rim and a wiped surface under the rim that is similar to those on facetted jars from the Upchurch/Thameside industry (Monaghan 1987, 91). Again, this vessel appears to have pitch on the rim, and the flint temper is similar to Monaghan’s F1/h: all of these factors point to an early Roman date for this feature. Several residual glauconite tempered sherds dating to the Iron Age were also recovered from the ditch and a small number of nineteenth-century glass fragments interpreted as intrusive. A small amount of fire cracked flint and a single fragment of cattle long bone were also recovered. An environmental sample taken from the ditch was devoid of macro plant remains, unlike the other samples taken from Romano-British contexts, but could be explained by the shallow depth of the ditch

In the eastern extent of the site a large double-ditched feature (Ditch 6) was recorded, which was interpreted to be turning north-south to east-west. The contexts that made up the double-ditch have been broken into three groups: the upper back/infilling that covered both ditches; the smaller (3.48m wide) external ditch and its dedicated fills and the larger (6.74m wide) internal ditch and its dedicated fills. Both of the ditches had a shallow U-shaped profile and no evidence of re-cutting was recorded.

The upper back/infilling that covered both ditch cuts contained the largest quantity of pottery (157 sherds) on the site, and was the only group to have any shell-tempered sherds (Fig. 4). The assemblage is mostly early Roman Upchurch/Thameside material, including a possible carinated platter with internal ridge, similar to 7B1.1 and 7B1.2 (Monaghan 1987, 159) in a fabric similar to Monaghan’s H1/4h (Fig. 5, no. 2). The illustrated examples are dated c. 43-70 and noted as being rare (ibid., 159). A piece of possible Roman tegula was also recovered as well as iron nails and a blade, also likely to be of a Roman date. A small quantity of worked stone was recovered including a few small chips and an elongated water-worn cobble, which has clear signs of it having been used as a hammer stone, with repeated impact damage at either end.

The bone recovered from the upper back/infilling consisted of six cattle fragments, including one from an immature animal, one sheep phalanx, a tooth from an immature pig (<16 months), a tooth from a horse (approximately 10 years old) and three small mammal fragments. One of the cattle longbone fragment displays chop and knife marks, the only butchery noted in the sites assemblage.

Three environmental samples were taken from contexts within this group. The samples were rich in a diverse range of cereals while chaff, other economic crop plants such as Pisum sativum, and wild/weed seeds were present in smaller quantities. Charred endosperm fragments were present in the group, which could be distinguished from charcoal fragments but could not be satisfactorily classified. Although there are relatively few charred fragments present there is a high taxon diversity suggesting the assemblage may have mixed origins rather than representing in situ activities. A small number of marine molluscus were also recovered during the excavation and from the environmental samples, including Oysters (Ostrea edulis) Mussels (Mytilus edulis) and Whelk (Buccinum undatum). The number of valves represented was insufficient for statistical analysis but distortion levels and shell size hint at a similar pattern of exploitation recorded from the lower external ditch (see below).

Excavation of the external ditch recovered 32 pottery sherds dating from the early Roman period. The pottery assemblage included a squat jar (Fig. 5, no. 1), which is similar to the wide mouthed everted rim jar form 3I1.2 that is ‘just on the “jar” side of the jar-bowl border’ (Monaghan 1987, 100). It is a wheel-made jar in a sand-tempered fabric and has a burnished shoulder with evidence of use prior to deposition as it is sooted. Monaghan gives this form a pre-conquest to pre-Flavian date, but the other sherds in the group suggest a date of c.50-70.

An environmental sample taken from external ditch contained a similar range of cereals, chaff and wild/weed seeds to those noted in the upper back/infilling. Pulses were more common in this ditch fill; unfortunately many of these are fragmentary and are classed as indeterminate. Within the fill of the external ditch a sealed ‘midden’ deposit of molluscus was recorded, which included Common oyster (Ostrea edulis), Common mussel (Mytilus edulis), Common cockle (Cerastoderma edule), Great scallop (Pecten maximus) and Great topshell (Gibbula magus). The midden deposit contained the largest assemblage of retrieved oyster on the site with a total weight of 5.548kg. Complete oyster shells from this context comprised of 110 left (lower) valves and 181 right (upper) valves and weighed 3.180kg. The remainder of the oyster assemblage was comprised of fragments. Age analysis of the valves indicates that c.56% of the 291 oyster valves collected/sampled were in the lower range (< 5 years) of the estimated ages. A significant number of the latter were juvenile. Furthermore, the entire assemblage was characterized by a small shell size in relation to their age (e.g. 5 year+ individuals typically having a breadth x height measurement of c.4 x 5 cm). Although evidence for encrustation was low within the assemblage (13 individuals with evidence of polychaete worm and 1 x individual with burrowing sponge), levels of distortion were very high (c.50%). The evidence suggests therefore that the oysters had been collected from a wild colony source that was probably being over-exploited and was certainly over-crowded.

The larger internal ditch had been truncated by the excavation of OAU’s Evaluation Trench 4, which was emptied by machine prior to the hand excavation of the feature. The excavation of the ditch recovered 18 pottery sherds dating to the early Roman period, including a large patchily-fired grog-tempered storage jar with a rolled rim and fine horizontal bands on shoulder. A small assemblage of animal bone was also recovered including a single fragment of cattle femur and a fragment of immature sheep (< 3 years). Environmental samples from the ditch showed that charred botanicals were less well preserved than in the exterior ditch and upper back/infilling and many indeterminate cereal and seed fragments were recorded.

Post-medieval

An east-west ditch, Ditch 7, was recorded between Ditches 2 and 3. The ditch contained a nineteenth-century Derbyshire ginger beer bottle stamped [S]HIPLEY POTTERY along with later medieval or post-medieval peg tile. A large levelling deposit of mid twentieth-century ‘Town Ash’ was recorded in the north-west of the site and numerous other features contained twentieth-century finds.

discussion

The later prehistoric features consist of Ditches 1, 2 and 3, and Pit 1. Ditch 1 seems to be a continuation of Ditch [1027], recorded during CAT’s excavation at Plot L2, Castle Road, which forms an enclosure, with Ditch [1016] demarking a possible droveway-like feature running to the south-east. Accurate dating of the later prehistoric features from CRS06 was problematic due to the lack of diagnostic sherds and the use of flint temper, which was used throughout the prehistoric and early Roman periods, as in the Upchurch/Thameside kilns, where flint temper is used until c.ad 70/80 (Monaghan 1987, 216). One flint-tempered out-turned rim sherd recovered from the overburden was almost certainly Roman in date, while flint-tempered pottery from CAT’s excavation was dated to the Late Iron Age. The presence of a later Bronze Age perforated clay slab also suggests that some of the flint-tempered pottery could be Bronze Age. Unfortunately, the pottery assemblage is too limited to further refine the dating. Although small, the worked flint assemblage of mainly hard-hammer waste flakes supports a later Bronze Age or Iron Age date. The animal bone assemblage is dominated by cattle with a few sheep and small mammal fragments. Where available, ageing data indicates mature animals.

Environmental samples taken from later prehistoric contexts contained very few charred botanical remains and the cereal grain and wild/weed seed assemblages were too small to provide detail regarding the crop economy or vegetation environment.

The Romano-British features consist of Ditches 4, 5 and 6, and Pit 2; Ditches 4 and 5 forming a droveway-like feature, which shares its alignment with later prehistoric Ditch 1, and might indicate continuation of use on the site. Quarry Pit 2 indicates that activities other than farming were taking place, such as the extraction of sand for use in building. Double-Ditch 6 is enigmatic as it sits on the edge of the excavation and does not have a comparison in CAT’s excavation to the north. Although wide, the ditches are relatively shallow and have a flattened U-shape indicative of a boundary ditch rather than having any military purpose. Evidence from environmental samples taken from Ditch 6 suggests that the botanical remains came from several different sources and were secondarily deposited suggesting that the double-ditch was deliberately infilled. This is supported by the midden deposit of mollusc shells, the quantity of which might suggest a purpose other than purely consumption debris, such as use as fertilizer or shell filler in pottery production. The pottery assemblage from the Romano-British features indicates a first-century date for the site, with almost all of the sherds likely to have been locally manufactured at the nearby Upchurch/Thameside kilns. The local products included a number of fine and coarse wares, including Hoo Island/Upchurch white-slipped ware; however, no large shell-tempered storage jars in North Kent shell-tempered fabric associated with these kilns were represented. A few Patchgrove grog-tempered sherds were also represented in the assemblage, a ware possibly produced in west Kent (Tomber and Dore 1998, 167). It is of note that the only non-regionally produced sherds in the whole assemblage are also the only sherds not dated to the first century. The animal bone assemblage was dominated by cattle with a lesser amount of sheep and rare examples of pig, horse and dog. The assemblage compares to CAT’s excavation to the north where the animal bone assemblage was dominated by cattle and sheep kept for meat and secondary purposes (Bendry 2003). The environmental remains from the Romano-British contexts were far richer in charred botanicals than those from the later prehistoric, and also contained non-cereal crop plants such as Pisum sativum (Table 1). Chaff makes up a very small proportion of each sample which suggests the cereal component of the deposits derive from the latter stages of processing. This contrasts with samples taken during CAT’s excavation where chaff was a more prominent component, plant remains were more common and the range of weed seeds more diverse (Pelling 2003).

The whole site appeared to have been horizontally truncated, probably during the site’s former use in the brick making industry, which could account for the shallowness of Ditches 4 and 5. This was particularly noticeable at the excavation’s north-western extent where the site had been truncated and re-levelled with ‘Town Ash’.

acknowledgements

The author would like to thank CgMs Consulting Ltd, and in particular Paul Chadwick, for commissioning and funding the work on behalf of their client (Saxon Shore Developments) and David Britchfield of Kent County Council for monitoring the site. The site work was undertaken by Mark Tibble (Surveyor) and Liz Chambers, Andy Margetts and Deon Whittaker (Archaeologists) and article production by Justin Russell and Fiona Griffin (Illustrators). The project was managed by Darryl Palmer (Senior Project Manager) and Louise Rayner (Post-Excavation Manager).

bibliography

ASE, 2006, ‘Specification for an archaeological excavation at Plot L1, Castle Road, Sittingbourne’, unpubl. report.

Bendry, R., 2003, ‘The animal bone’, in CAT report.

CAT, 1998, ‘Highway infrastructure for Eurolink Phase III, Sittingbourne, Kent: an archaeological watching brief December 1997-February 1998’, unpubl. report.

CAT, 2003, ‘A Late Iron Age and Early Roman site at Castle Road, Sittingbourne, Kent’, unpubl. report.

Denison, S., 2000, ‘Regular villas for Roman colonists in Kent’, British Archaeology, no. 53, June 2000.

Detsicas, A., 1983, The Cantiaci, Alan Sutton Press, Stroud.

Lyne, M., 2003, ‘The pottery’, in CAT report.

Monaghan, J., 1987, Upchurch and Thameside Roman Pottery: a ceramic typology for northern Kent, first to third centuries AD, BAR British Series 173, Oxford.

OA, 2005, ‘Plot L1 Castle Road, Sittingbourne’, unpubl. report.

Pelling, R., 2003, ‘The Charred Plant Remains’, in CAT report.

Sparey-Green 2000, ‘Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment of proposed factory/industrial site, Castle Road, Sittingbourne’, unpubl. CAT report.

Tomber, R. and Dore, J., 1998, The National Roman fabric Reference Collection: a handbook, MoLAS Monograph 2, London.

Yates, D., 2004, ‘Kent in the Bronze Age’, in T. Lawson and D. Killingray (eds), An Historical Atlas of Kent, Phillimore.

Fig. 1 Site Location.

Fig. 2 Plan of trenches and archaeological features.

Fig. 3 Plan of CAT excavations at Plot 1, Castle Road, showing possible continuation of Ditch 1 (ASE Ditch 1027). (CAT)

Fig. 4 Section showing upper back/infilling, exterior and interior components of Ditch 6.

Fig. 5 Illustrated sherds from Roman assemblage.

Table 1. Macrobotanical remains quantification

|

Ditch |

Pit |

Ditch |

||||||||

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

LBA/LIA |

LBA/LIA |

LBA/LIA |

LBA /LIA |

RB |

RB |

RB |

RB |

RB |

RB |

|

|

Sample No. |

3 |

6 |

10 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

8 |

7 |

9 |

|

Context No. |

43 |

51 |

49 |

13 |

25 |

45 |

47 |

54 |

52 |

57 |

|

Indeterminate cpr |

30 |

75 |

1 |

|||||||

|

Cereal Grain |

||||||||||

|

Triticum cf. dicoccum |

1 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

|||||

|

Triticum spelta |

3 |

5 |

6 |

11 |

||||||

|

Triticum aestivum |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

||||

|

Triticum sp. |

1 |

8 |

11 |

1 |

10 |

7 |

||||

|

Hordeum vulgare |

1 |

5 |

2 |

7 |

6 |

12 |

||||

|

Avena/Bromus sp. |

1 |

7 |

4 |

7 |

14 |

|||||

|

Indeterminate |

2 |

3 |

1 |

32 |

5 |

15 |

28 |

75 |

||

|

Cereal Chaff |

||||||||||

|

Trit. spelta glume base |

8 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

||||||

|

Trit. Dic. glume base |

2 |

1 |

||||||||

|

Trit. sp. glume base |

3 |

|||||||||

|

Trit. sp. glume frag. |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Trit. sp. rachis internode |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Other Cultivated Plants |

||||||||||

|

Pisum sativum |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|||||||

|

Indeterminate pulses |

4 |

2 |

5 |

17 |

||||||

|

Weed/wild seeds |

||||||||||

|

Vicia/Lathyrus sp. |

4 |

|||||||||

|

Polygonum/Rumex sp. |

2 |

8 |

3 |

|||||||

|

Malus sp. |

5 |

2 |

||||||||

|

Galium sp. |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|||||||

|

cf. Brassica sp |

3 |

1 |

||||||||

|

Graiminae seed |

1 |

1 |

||||||||

|

Indeterminate |

1 |

3 |

9 |

30 |

27 |

70 |

||||

|

Mineralised Botanicals |

||||||||||

|

Indeterminate |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Uncharred Botanicals |

||||||||||

|

Chenopodium sp. |

2 |

|||||||||

|

Rubus sp. |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Solanum sp. |

4 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||

|

Indeterminate fruits |

2 |

|||||||||

|

Ditch |

Pit |

Ditch |

||||||||

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

LBA/LIA |

LBA/LIA |

LBA/LIA |

LBA /LIA |

RB |

RB |

RB |

RB |

RB |

RB |

|