The Roman and Medieval Defences of Rochester in Light of Recent Excavations

Contributions to the next volume are welcome. See the guidance for contributors and contact Editor Jason Mazzocchi. Also see the guidance for peer review.

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Previous

Previous

John Marsham, A Forgotten Antiquary

Next

Next

The Old Mill Bexley

The Roman and Medieval Defences of Rochester in Light of Recent Excavations

Written By Jacob Scott

Aiver Medwo y

Cost le

Presumed

Site of Roman South Gate .,,,,

ROMAN

RO C

& MEDIEVAL

H if" S TE

Based on G.M. /J,ivett. Arch. Cont.,

xxi (teps).

50

R

l ---------- --

Metres% 50

I

100

I Yards

Fxo. 1.

Presumed

"Site of Roman North Gate

Remains of Rom'on

East Gate

[f.U p. 55

THE ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER IN

THE LIGHT OF RECENT EXCAVATIONS*

By A. C. HARRISON, B.A., and CoLIN FLIGHT, B.A.

THIS is an account of a series of excavations in Rochester, jointly

undertaken by the writers between 1960 and 1966; but, in the absence

of Mr. Colin Flight abroad, it is only right that the responsibility for

any shortcomings should rest with the first-named, who prepared it for

publication. The account of the first excavation near Northgate

(Northgate A) is by Mr. P. J. Tester, F.S.A., who directed it.

Initially, there was no intention to challenge the accepted account

of the history and development of the defences of the city; in fa.et, the

original excavation was merely an attempt to date the Roman wall,

a problem which still lacks a definite solution. Each excavation, however,

posed questions demanding further enquiry and made inevitable

a reconsideration of all the relevant evidence, both documentary

and archooological. For the Roman period, our findings are additions

to the accepted account, but our view of the sequence of events for

the medieval periods differs radically from that of our predecessors.

The Roman defences of Rochester were last treated systematically

in 18951 when George Payne, for the first time, correctly identified

portions of the city wall as Roman and traced its circuit on the south,

east and north sides of the city (the exact line on the west side facing

the Medway was then, and still is, unknown);2 in the same publication

Canon G. M. Livett described the development of the medieval defences

for which there are two main sources of documentary evidence ;3 firstly,

a series of entries in the Close Rolls of 1225-27 describing payments made

for work in Rochester which included a new ditch and, secondly,

documents relating to the grant to the Priory by Edward IlI in 1344

of that part of the ditch extending from the Prier's Gate to the east

gate.

Briefly, Canon Livett considered that the Roman wall was intact

to the end of the Saxon period and underwent several extensions starting

from the time of Gundulph (1077-1108). The position of the walls

• This pa.per ba,a been printed with the aid of a grant from the Council for

British Archroology.

1 His account was to some extent supplemented by R. E. M. (now Sir

Mortimer) Wheeler in V.O.H. Kent, iii, 80 and 88.

1 It bas been a. convention, since at least the seventh century, to regard the

city as ba.ving its long axis due east-west.

3 These a.re given in full by St. John Hope, A.rch. Oant., xxiv (1900).

55

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

and ditches mentioned below is given in Fig. 1 and, diagrammatically,

in Fig. 2. These were:

(a) A rectangular enclosure round the old Bishop's Pa.lace whose

north wall coincides with the Roman city wall, which Canon Livett

ascribed to Gundulph or his successor, Bishop Ralph (1108-14), and

considered that the small length of much-patched wall at the junction

of St. Margaret Street and Boley Hill Street, site of the second South

Gate, belonged to this enclosure.

(b) A long narrow strip running from the south-east corner of (a)

to a few feet south of the Roman south-east angle. Canon Livett

considered that Prior's Gate, or rather its twelfth-century predecessor,

as the present gate can hardly be earlier than the late-fourteenth

century and may be later, belonged to this wall, ascribed to Bishop

Ernulf (1114-23).

(c) Following the capture of Rochester in 1215 by King John, the

great ditch mentioned by the Rochester chronicler was begun in 1225;4

according to Canon Livett this ditch ran south from Eastgate, turned

west near the Roman south-east angle and continued just to south of

the wall mentioned in (b) above. At the west end, he considered it swung

further to south to enclose Boley Hill and, spanned by a bridge or

causeway, to give access both to the second Southgate and to Prior's

Gate.

(d) Canon Livett thought that in 1344 this ditch was filled in and

replaced by a new one further south and a wall was built along its

northern lip as far as Prior's Gate, which he considered was rebuilt

then. The east wall of the city was e:x:tended to meet this new wall

which Canon Livett claimed to have 'traced throughout its course',

but in fact the tracing was done with the probe.

(e) At some unknown later date, another wall was built enclosing

a further area to south, including the ditch mentioned in (d) above,

and the east wall was again e:x:tended with a bastion at the south-east

corner.

This account was in pa.rt challenged by St. John Hope who accepted

the early Norman and later Norman extensions and agreed that the

documentary evidence shows a ditch dug in 1225. He identified this,

however, with the one visible in the Deanery orchard and considered

that the wall along its lip was built at the same time, although not

specifically mentioned in the Close Roll entries. This enabled hlm to

equate the still existing wall near the Vines with that authorized in

1344, but he had to admit that the provisions of the charter were not

fully carried out, for neither was the eastern part of the earlier ditch

filled in nor was there any trace of the new ditch. The position of these

walls and ditches is shown in Fig. 1 and, diagrammatically, in Fig. 2.

' 2 Cott. M.S. Nero D.2. 132, cited by St. John Hope.

56

ROCHESTER

N

N

C D

Reconstructed North-South Section

Alter G.M. livett

{ - r L,, _ ,

Romo"n Woll

,.

After W.H. St.John Hope

I L., 7' ., ...:.il

Romon Woll

A.C.H. mens.

ltr

/0

* ..

20

I 9 6 3 5

E

Sookowoy

--

'Ernu/1/011' Woll

( J

,,L....,J

Lute- Norman Wal/-

JO 40

Grovel

50

,I

1225 Ditch

I Feet

H

16th Centu ry:':,,;;----1.μ,,i.J.J-'A

Pit

1225 Ditch

0 s

FIG. 2.

D e a n e r y

G

Romon PU

G a r cl e n

,.

( 1

..L....,...,..J

1225 Wc,/1

10 IS

Metres

s

s

[face p. 50

ROCHESTER

Rom o n

Mediev al

D Modern

New Deanery

S 0 /0 20

Fee t

I 9 6 .J .. S b._.

I

--.

. I

lcioy Romporl

Gorden Woll

Inner race,

excavated by -

Llvett,/89S

1

,,...

"\ oloss House

'

J /

Deep Sookowoy

16th Crmtury Pit

Conons'Houses

.JO 40 I O s

Metres

10

FIG. 3.

f 1nn<1r L.I'

. no PosW0

·,note

Approx,

.-

K\ .,.

.-

.\- -\

p\ \

,_ \

- ':7

0\ I

\_.

[facep. 57

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

TB:E ExoA VATIONS

Culling A. (Fig. 3 shows the positions of all these cuttings, except

Northgate A and B.) In 1961 Cutting A (Section e-f) was excavated

against the inner face of the Roman wall which, though completely

buried internally, here survives to a height of about 16 ft. On the other

side of the Roman wall the upper part of its facing is visible but, as

the lowest few courses have fallen away, the underpinning is modern.

At the bottom of the cutting (Fig. 4) a layer of dark earth, 5 in.

thick, overlaid clean orange brick-earth. At the extreme western end

of the cutting was a small round pit cut into the brick-earth and containing

an urn in white-slipped red ware (Fig. 15, no. 56). There was

no sign of anything else in the pit nor of anything in the urn. The

pottery from the dark earth (Layer 9) was of the third quarter of the

second century A.D. and also contained a fragment of a pseudo-Venus

figurine.° Flints and earth formed the foundation of the remains of

the Phase I rampart consisting of alternate layers of blue clay and dirty

yellow sand (Layer 7). The rampart had survived only to a maximum

height of 3 ft. 6 in. and, on the evidence of the pottery, cannot be

earlier than the third quarter of the second century A.D. There is no

more precise terminus ante quem for the rampart than the construction

of the wall, though there are indications {e.g. the small amount of silt

in the ditch belonging to it),6 that its life may have been fairly short.

The foundation of the Roman wall (Phase II) was a layer of concrete

some 15 in. thick, though it is possible that deeper digging would

have disclosed a foundation trench as well, similar to that in Cuttings

B and C. This concrete raft (Fig. 4, Layer 11) was approximately 8 ft.

wide; set back 6 in. from its edge, the bottom course of the internal

facing projects to form a plinth 6 in. wide. For the next six courses

the face is 'battered' until an 8-in. offset reduces the thickness of

the wall to 5 ft. 10 in.; the next seven courses are vertical up to where

another offset, 12 in. wide, further reduces the thickness to 4 ft. 10 in.

Five more courses of the facing are intact; then the core is exposed

to a total height of 16 ft., and it is likely that only the foot-walk and

the parapet have been lost. The core consists ofragstone rubble liberally

grouted with hard gritty brown mortar; no use was made of lacing

courses of bonding-tiles. The face is of untrimmed ragstone, coursed

and heavily pointed with the same mortar. The pointing of the inner

face of the wall was unweathered, showing that it had been protected

by earth piled against it from the outset. This wall-bank (Layer 5),

covered the face of the wall to a. point just a.hove the upper offset

and enclosed the stump of the Phase I rampart.

a Mr. Fre.nk Jenkins, M.A., F.S.A., kindly identified tWa fragment as

originating in the Allier area.

• As shown in Cutting D (Fig. 6),

57

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

CUTTING A

40'6"0.D.

. . . . .. . . 3· .

. . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

. .

9

1

I

I

I

I

I

Section e-1

- - '

ROMAN

WALL

'

SE

'I'.,

'' :' . .

/ :

. .

. .

. '

. .. . .

- - - - - - _,_ -4 . . ...... // : .'

-- - - -..!..--t'

' - - - --------

I

'

I

I

I

Flo. 4. Cutting behind Roman wall at its south-east angle. 1. Post-medieval

debris. 2. Dark soil a.nd yellowish sand. 8. Dirty brick-earth. 4. Filling of medieval

pit. 5. Roman wall-bank. 6. Sandy fill of wall foundation trench, divided by

mortar-scatter. 7. Rampa.rt. 8. Layer of flints forming foundation of 7. 9. Secondcentury

occupation layer. 10. Pit with vessel no. 56 (fig. 15). 11. Conoret.e raft of

flints in hard brown mortar.

58

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

In Eagle Court the much-weathered external facing of squared

ragstone blocks regularly coursed is intact above the level of the lower

internal offset. George Payne observed7 that the lowest courses of the

facing extended back into the core. If this were the case (and nothing

of the sort was to be seen internally), they must have formed ashlar

bonding-courses and cannot be the foundation, as he supposed, because

they are approximately 4 ft. above the actual base of the wall. The

south-east angle forms a regular curve with an external radius of about

32 ft. and lacked indications of either an external bastion or of an

internal tower.

The construction trench between the Phase I rampart and the

wall was filled with layers of brick-earth, separated by a thin spread

of mortar-scatter resulting from the building of the wall (Layer 6).

A large medieval pit had been dug through both the wall-bank and

the remains of the Phase I rampart (Layer 4). The top of the overlying

deposit of dirty brick-earth (Layer 3) is at about 30½ ft. above O.D.

against the wall and has a very slight slope to the west. A similar

levelling is apparent inside the wall in the Deanery Garden (Cutting C)

at about 29½ ft. above O.D. and is probably to be connected with the

back-filling of the 1225 Ditch. If that is so, it is probable that this

surface also represents the same mid-fourteenth-century horizon, of

which there are other indications to the west and south.

Layer 3 was overlaid by a midden of dark earth streaked horizontally

with yellow sand {Layer 2); it contained pottery of c. A.D.

1300, like the preceding layer, and including a grey-ware jug (Fig. 16,

no. 75). There was also part of a louver (see Appendix I), and a small

stone mould (see Appendix II) which point to a fourteenth-century

dating for this layer.

Deanery Garden, 1962-65. With the object of discovering whether the

Phase I rampart found at the south-east corner continued to the west,

excavations were begun in 1962 among the trees at the end of the Old

Deanery lawn (TQ 74366838). Cutting B was sited 2 ft. to the west of

the point where George Payne dug in 1894, and proved to be directly

south of the line of the Roman wall (Fig. 3).

Gutting B (Section c-d). (a) The earliest features were the truncated

remains of a comple.x: of nine pits and four gullies, with very little

datable material (e.g. Fig. 13, nos. 20 and 21}. So little was left of the

pits and gullies of this ea.rliest period, amounting to no more than

a few inches in each case, that no firm conclusions as to the nature

of this OCQμpation could be reached, except that there was some

unidentified activity during the late.-fust o r early-second century A.D.

(b} Approximately 3 ft. 6 in. from the south end of the cutting the

lip of a ditch rumung east-west-was traced; it was filled by precisely

1 Arch. Oant., xxi (1896).

59

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

SOUTH

CUTTING 8

Sttf/011 c-d NORTH

2

4---------···-

10

SCALE 11'1 FEET

Flo. 5. Cutting B, across line of south Roman wall in Deanery Garden. 1. George

Payne'e excavation, 1894. 2. Tudor debris. 3. Mortar back-fill of wall-robbers'

trench. 4. Brown soil with tiles and debris. 5. Medieval domestic rubbish and

Roman mortar rubble. 6. Medieval filling of brown soil and rubble. 7. Medieval

accumulation of dark soil and rubble, 8. Rema.ins of Roman wall resting on

foundation of flints and brick-earth. 9, Ditch of pre-wall defences, back-filled with

clay over silt. 10. Filling of first-century gully (G.l).

the sa.me mixture of blue clay and dirty sand noted in the construction

of the Phase I rampart in Cutting A, though the proportion of clay was

higher (La.yer 9). Trees prevented further extension to the south (but

see Cutting D, below).

( c) At the north end of the cutting was the south face of the Rom an

wall, here demolished down to the concr ete foundation, though a

very large lump of the core rested upon this. This concrete raft was

1 ft. 3 in. thick and rested upon a foundation-trench 2 ft. 8 in. deep,

alternately filled with rammed flints and brick-earth. (For a complete

section, see Cutting C.)

60

SOUTH CUTTING D

2

1---------------- ---··-··· --·--- ----1

---- --··-· -·-· .. --····--·---l

1-----------= 6 =--

----·-· ··- - ·-·-·-----·-···----1

---····· ·--·--··

UN EXCAVATED

Section a.I,

.Jl'B"QD.

'

'

CUTTING C

·Fxo. 6. Cutting C and Cutting D, across line of Roman wall in Deanery Garden.

1. George Payne'a excavation, 1894. 2. Post-medieval build-up of tiles and

building debris. 3. Mortar and tile back-fill of wall.robbers' trench. 4. As for 2.

5. Soil and rubble. 6. Medieval filling of soil with tiles, rubble and domestic refuse.

7. Mortar r ubble. 8. Medieval turf.line. 9. :Medieval filling of soil and chalk rubble.

10. Flinty gravel. 11. Remains of Roman wall. 12. Foundation of wall composed

of layers of flints and brick-earth. 13. Olay rampart (Phase I). 14. Gravel rampart

material (Phase I). 15. Sandy rampart material (Phae I). 16. Phase I ditch backfilled

with clay over silt. 17. Flint foundation of rampart. 18. First• to secondcentury

occupation level.

/

/

4

SCALE IN FEET

NORTH

1 I. I

[facep. 01

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

(d) All other Roman levels had been removed by an excavation

which extended from the face of the wall to the southern limit of the

cutting. The excavation had been back-filled by a mass of material

containing medieval pottery. Four layers were distinguishable, but

the pottery from Layers 4-6 does not differ appreciably in date,

which is considered to be c. A.D. 1300 (Figs. 16-17, nos. 79-94).

This large medieval excavation is fairly confidently to be identified

with the ditch known from documentary evidence to have been dug

in 12258 and which the monks of the priory obtained leave to fill in

1344,9 Layer 7 may represent the surface of the 1225 Ditch while it

was still open. On the surface of Layer 4 a small drain, made of ragstone

and floored with roofing-tiles of unusually large size, 11 in. X 7½ in.,

crossed the cutting obliquely near its centre and discharged into a

circular soak-away pit, 2 ft. 6 in. in diameter, filled with stones and

broken roofing-tiles as well as numerous fragments of a large grey

cooking-pot with slight shell-filling (Fig. 17, no. 95). Ai, this pot was

clearly not a rubbish survival, it may indicate that this common

thirteenth-century form continued in use until the middle of the

fourteenth century.

(e) Above the medieval filling and directly below the topsoil was

Layer 1 consisting almost entirely of building debris and architectural

fragments with pieces of 'billet' ornamentation paralleled on the

Norman west front of the Cathedral (Fig. 18, no. 7). This layer, which

has been found to extend for a considerable distance and to contain

sixteenth-century material, is considered to represent a levelling of the

area after the demolition of monastic buildings, either in 1541-42, when

the cloisters were being converted into a house for Henry VIII or, more

probably, after 1558 when Lord Cobham sold the site of the Priory

to the Dean and Chapter.

Cuttings O and D. (Section a-b.) With the double purpose of obtaining

a continuous section across the wall and the Phase I rampart,

if present, and of investigating the ditch discovered at the south end

of Cutting B, Cuttings C and D were opened 2 ft. to the west of B and

overlapping it at either end with a 6-ft. baulk between them (Fig. 6).

(a) The earliest period noted in Cutting B wM represented in Cutting

C by the large Gully G.l which ran obliquely the length of the cutting,

passed beneath the wall and through Cutting B in a southerly direction.

It was 5 ft. wide and 2 ft. 6 in. deep, had a flat bottom and sloped southwards

fairly steeply. Pottery from the filling was scarce, except for a

few Roman sherds suggestive of mid-first-century date.

(b) The filling of the gully was covered by Layer 18 which may be

identified with the top-soil in the middle of the second century as it

8 Arch. Oant., xxi (1895),· 51, and xxiv (1900), 12 ff.

0 Arch. Oant., xxiv (1900), 16 ff.

61

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

contained Antonine pottery, and above this was the gravel foundation

(Layer 17), of the Phase I rampart (Layer 13). The rampart itself,

which was of the same construction as previously noted in Cutting A

(see p. 57 above) survived to a height of 2 ft. 6 in. The bands of clay

which were thick and close together at the south end tapered off to

the north. Evidently, the clay formed a facing or revetment of the

bank and was bonded back into it. The top of the surviving portion

of the rampart was more or less flat with only a thin layer of ruhbly

earth separating it from the sixteenth-century debris above and there

was no trace of a wall-bank overlying the cut-back rampart as in

Cutting A.

(c) In Cutting D the profile of the ditch located at the south end

of Cutting B was exposed (Layer 16); it was V-shaped in section with

its deepest point about 8 ft. 6 in. below the estimated Roman ground

level. It had, of course, been truncated by the medieval ditch, but, if

the sides are projected to the level of the original surface, a width of

about 20-22 ft. seems likely. This agrees fairly closely with the dimensions

of the first-century ditch at Verulamium which was found to

be approximately 9 ft. 6 in. deep and 19 ft. wide at one place1° and 10 ft.

deep and 22 ft. wide at another.n A small amount of fairly clean silt

(Layer 19) had accumulated in the bottom. Above this silt the ditch

was filled with material identical with that of the Phase I rampart.

The conclusion seems inescapable that this filling was derived from

cutting back the rampart when the wall was built and that the ditch

it was used to fill belonged to the same defensive system. Presumably

it was thought to be too close to the wall for re-use in Phase II.

(d) (Plate I). A complete section was out across the wall foundation,

which was all that remained at this point (Layers 11 and 12). About

15 in. of the south edge of the concrete raft had been eroded M a

result of the medieval ditch being dug right up to its face. Immediately

above the concrete raft was a quantity of mortar debris (Layer 3)

which probably represents the remains of the robber-trench mostly

obliterated by George Payne's excavation.

(e) The medieval layers to the south of the wall presented much

the same picture as in Cutting B except that the filling of the ditch

was more homogeneous and the line representing the weathering of the

surface of the ditch more clearly defined. Again, at this level quantities

of Roman mortar suggestive of demolition had been dumped. A large

oval pit 4 ft. 6 in. X 3 ft. 6 in. x 8 ft. 6 in. had been dug from the level

of the turf-line through the lower medieval layer and the filled Phase

I ditch into the subsoil. The filling of dark earth produced a bone comb

of early medieval type (Fig. 18, no. 2). From the earth at the top of

10 S.S. Frere, 'Excavations at Verulamium, 1955' ,Antiq. Journ., xxxvi (I 956), 4.

11 Antiq. Joum., xli (1961), 80.

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

the pit, however, under a clay seal, came a few fragments of glazed

pottery identical with those from the layer above it and indicating

that the sealing of the pit and the filling of the ditch were probably

contemporary. The medieval pottery from Cutting D was similar to

that from Cutting B (Fig. 17, nos. 96-107).

(f) The layer of sixteenth-century building debris was continuous

across Cuttings C and D except where interrupted by George Payne's

excavation.

The results of these excavations therefore were, firstly, that the

presence of the Phase I rampart and ditch on the south side of the

Roman town was established and, secondly, that the medieval excavation

south of the wall was shown to extend for at least 20 ft.

OuUing E (Section g-h). The above results immediately called in

question the identification and dating of the wall whioh both Canon

Livett and St. John Hope show as running from Prior's Gate to the

north-east corner of the Deanery Garden, described as the 'later Norman

wall' and attributed to Bishop Ernulf (1114-24) (Fig. 3). Cutting E

(Fig. 7) was therefore made across the known line of this wall which

S

CUTTING E

Svction g-h N

1

WALL

'

FEET

Fta. 7. Cutting E, through Livett's 'Ernulnan' wall. 1. Broken roof-tiles. 2. Sandy

soil with tiles and chalk. 3. Flints, chalk and tiles. 4. Sandy soil with tiles and

flint rubble. 5. Sandy soil with chalk. 6. Coarse gravel. 7. Medium gravel.

8. Coarse gravel.

63

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

was found to exist to a height of 3 ft. with a 4-in. projection at the

bottom above a foundation layer of large lumps of ragstone and flint.

(These were not laid obliquely as described by Canon Livett.)12 Its

width was 2 ft. 8 in. and its construction was of fairly small pieces of

ragstone, roughly coursed and with the mortar joints set with small

pieces of stone in the manner known as 'garretting'. The face of the

cutting to the south of the wall disclosed an important fact. Under

the usual sixteenth-century layer of building debris, five layers of earth

and gravel sloping at about 45° from south to north were distinguishable.

The three lowest layers all ran underneath the foundation

course of the wall, which was therefore very clearly built on and into

'made' soil.

Although this tipped material of clean gravel differed from that in

Cuttings Band D, it seemed certain that it formed part of the same

process of back-filling and, as this could not be earlier than c. A.D. 1300

on the evidence of the pottery and was probably later than A.D. 1344

on the documentary evidence, it was clear that the wall could not

possibly be earlier than the fourteenth century. This conclusion was

supported by an examination of the structure itself: not only did it

seem inadequate for a defensive wall, being narrow and with very slight

foundations, but the masonry itself was quite unlike any known Norman

work in Rochester. Finally, the practice of garretting does not seem to

be usual before the sixteenth century which makes it probable that this

wall was erected in connection with the conversion of the Priory in

1541-42.

Cuttings F and G-H (Figs. 8 and 9). The identification of the

medieval ditch and the doubt cast upon the 'later Norman wall'

CUTTING F

)' ·c ,, !

I

I

· ·---

'

'\

'

'

GAROEN PATH

I -·- --· -

-

I

I

1

·-· --

2

I.

=-,

---

Ill

Sect/of/ i-i

.. -

I

FIG. 8. Cutting F, through channel under path in Deanery Gorden. I. Topsoil.

2. Soil containing rubble and tiles. 3. Dark soil containing rubble, tiles and mortar.

11 Arch. Oant., xxi (1895), 50.

64

SOUTH

If)

()

)>

rI'll

z-n

I'll

C

CUTTING H

d

....

• I

•••••

•

• •• •'1

. . . • ·

1

/.

NORTH

3

Loyers 5-7, /225 Ditch Filling .

: : -: . :_:-:. ·.: .· .· : :_. ·_. :- ·_. .

-----

---

----- CUTTING G

Section k-1

Fro. 9. Cutting G and Cutting R, through filling of medieval

ditch and Roman pit. 1. Tiles, etc., filling pit or re-cut

channel. 2. Silting of channel. 3. Tudor debris. 4. Dirty brickearth.

5. Si.ndy gravel. 6. Coarse sand. 7. Dirty brick-earth.

8. Silt. 9. Silted gravel and sand.

Natural deposits: a. Brick-earth. b. Yellow melt-mud. c. Sandy

gravel. d. Sand and pebbles.

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

suggested that the next point to be investigated should be the southern

extent of the ditch and the wall presumed to lie to the south of the

former beneath the grass path in the Deanery kitchen-garden (see p. 56,

para. (d) and Fig. 2). For this latter purpose Cutting F (section i-j) was

cut across this path and it wa-s found that this overlaid a channel cut

into undisturbed brick-earth. This channel was 12 ft. wide and 3 ft. 3 in.

deep with sloping sides and was filled with building debris, mostly

roofing-tile.13 There were only two pieces of pottery recovered, both

probably of Tudor date. Of the wall there was no trace whatever and the

channel cannot reasonably be interpreted as a robber-trench.

Cutting G (Fig. 9, Section k-1) was sited with the intention of finding

the lip of the medieval ditch, but fell short of it. At this point the layer

of sixteenth-century building debris (Layer 3) was much thicker and

should be regarded as part of a. pit; it contained a. sixteenth-century

German brass jetton having the arms of Wertheim.14 Beneath this was

the same clean gravel noted in Cutting E with tip-lines again running

from south to north and followed by dirty brick-earth. One significant

point was noted: the natural geological sequence here is reddish brickearth

and then, after a narrow band of pale yellow melt-water mud,16 a

sandy gravel. In the :filling of all the southern portion of the medieval

ditch the order is reversed with brick-earth at the bottom, indicating

that the material was dumped in the order in which it was dug out from

another deep excavation. This can hardly have been other than the

ditch still visible in the orchard to the south, which Canon Livett,

correctly it would seem, considered to be the one authorized in 1344,

whereas St. John Hope identified it with that of 1225 (see Fig. 2).

Cutting H was then made as an extension to the south of Cutting G

and presented a rather complex picture. The earliest feature is a deep

excavation reaching no less than 19 ft. below the surface and containing

some Antonine pottery at its lowest level. The south end of the section

had been distur bed by the channel noted in Cutting F, here 10 ft. wide

and 3 ft. 6 in. deep (Layer 2) which had apparently been recut before

being finally filled in with tiles and debris (Layer I). This channel

ma.de it impossible to define the exact lip of the 1225 Ditch at this point.

The sequence appears to have been as follows: a deep excavation of

unknown e;xtent was dug in the Antonina period or later. It is possible

that this may represent the southern lip of the ditch dug in front of the

Roman wall, if this was steep-sided and with a flat bottom, contrasting

with the V-shaped profile of the ditch associated with the Phase I

1s It is suggested that this was what Canon Livett felt with his probe (Arch.

Gant., xxi (1895), 62.

l& Miss M. Archibald of the British Museum kindly provided this identification.

l5 Apparently a sludge-deposit of the kind described by M. P. Kerney, in

'Late-glacial Deposits on the Chalk of South-east England, Phil. Trans. lfoJt.

Soc. L to the end of the third century any final judgement must be

reserved. The table on the facing page summarizes the evidence available.

There is some slight evidence of a third period of the defences (Phase

III) near the north-west angle. In 188936 according to George Payne the

town wall was exposed at a distance of about 100 ft. from the river and

is described as being 7 ft. thick, of rags tone in hard pink mortar with a

double bonding-course of tile. A. A. Arnold in 188737 described a similar

33 Arch. Gant., xxvii (1905), lxix•lxx.

8' A. L. F. Rivet, Tawn and Oount1-y in Roman Britain, London, 1958, 90-92.

On the other hand! Professor Frere has already suggested a. date still later 'in the

first. half_of the third century, perhaps under Alexander Severua or Gordian III'.

(Brua,n,nia, 263.)

35 For Reculver see J.R.S., li (1961), 191, and lv (1965}, 220· Antiq Journ

xli (1981), 224-8. ' ·•

For Canterbury, see S.S. Frere, Roman Oanterbury 3rd ed. p 10

36 Arch. Oant., xxi (1896), 8.

' ' · ·

31 Arck. Gant., xviii (1889), 1.94.

76

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

DATlNQ EVIDENCE FOlt ROll!AN DEFENCES

Coarse

wa.Tea Samian Suggested

Cutting Context (Figs. (Fig. 15) da.ting

13-14)

PHASE I

Z6 50-75 Earlier deposits C Gully l

sealed below Layer 18 22-24 150-175

ra.mpaTt A Layer 10 66 75-100

Layer 9 40-42 150-175

B Pits in

Layer 10 20-21 80-120

Foundation layer of C La.yer 17 19 150-175

earth and flint.a A La.yer 8 27-30 170-190

Body of rampart C Layer 13 16-17 150-175

Layers 14-15 31-35 150-175

A Layer 7 36-39 5 170-190

PRAsE n

Earlier deposits,

B Layer 16 18 170-190 Northgate

Wall-trench B Layer 8 25 170-190

Body of wall-bank A Layer 6 46-47 170-190

Layer 5 43-45 170+

Northgate B Layer 12 1-15 1-4 170-190

fragment of wall in the same area cut through by a. drain as 'undoubtedly

Roman' whloh in context means almost certainly that the

mortar was pink. Thls seems to suggest a. wall very different from that

found elsewhere, and closer, for example, to the late third-century work

at Richborough.88

0. Saxon. The survival of the Roma.n defences is attested by the

description of the city as a 'castellum' in charters of the seventh-ninth

centuries and by reference to the walls and gates in the same documents

and in accounts of the unsuccessful siege by the Danes in A.P. 885.

D. Norman. The circuit of the Roman wall continued in being

during the Norman period, though the building of the Castle towards

the end of the eleventh century must have involved alterations in the

south-west corner, as the defences of the castle seem always to have

been independent of those of the oity. A length of the Roman wall near

Southgate, and possibly part of the west wall as well, must therefore

have been demolished when the oastle-ditoh was dug.

It will be remembered that both Canon Livett and St. John Hope

considered that two extensions were ma.de to the south during this

period, but neither of these now seems supported by the evidence. The

suggestion of an early-Norman rectangular extension enclosing the

38 J.P. Buiihe-Fox, Exca.vationa of the Roman Fort a.t RichboroughIV, Oxford,

1949, 81.

77

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENOES OF ROCHESTER

Bishop's Palace depends upon two points: firstly, the identification of

a small piece of much-patched wall as being of that date (it will be

shown that it is more probably of the fourteenth century) and secondly,

upon the existence of three documentary references to the Bishop's

Palace;39 the first dates from the time of Gundulph, the second relates

to a re-building by Gilbert de Glanville soon after 1185 and the third

occurs in a document of 1459 which Bishop Lowe dated 'from his new

palace at Rochester'. It is only in the last case that there is a clear

correspondence between the document and the existing building

located on the line of the Roman wall and the reference to the 'new

palace' could be taken to mean that it was built here for the first time:

Gundulph's and Gilbert's palace may well have been elsewhere. The

'later-Norman extension' ascribed to Bishop Ernulfwas bounded by the

wall investigated in Cutting E. This excavation showed conclusively

that this wall must be later than the fourteenth century and the style

of the wall suggests the sixteenth. In his account of this extension

Canon Livett shows a drawing4° of what he takes to be the continuation

of this wall at the east end of Minor Ca.non Row. It is, however, very

different in character and the sketch suggests that it Wa.':! sunk into the

filling of the 1225 Ditch.

E. Thirteenth century. The 1225 Ditch referred to by the Rochester

chronicler and in the Close Roll entries may with some confidence be

identified with the great excavation shown to extend from the south

face of the Roman wall to a point about 100 ft. further south.41 This

ditch seems to have had sloping sides and to have been of considerable

depth in the centre (the bottom was not reached even in the deep

soak-a.way, which reached a depth of 24 ft. from the present surface).

It is not quite established whether the 1225 Ditch continued to follo,v

the line of the Roman wall all the way to Southgate, leaving the

Refectory (and possibly the Palace) projecting into it like towers, but

there are two indications that it may have done:

(I) Canon Livett's drawn section41a of the wall he found at the east

end of Minor Canon Row shows the sloping side of an earlier ditch

running beneath the wall with its lip a.bout 8 ft. from it which can

hardly be a foundation-trench as he suggests. Unfortunately, since the

orientation is not given, this could either be the inner lip of a ditch

87 ft. from the Roman wall or the outer lip of one 106 ft. from it. In the

so Arch. Oant., xx:iv (1900), 60.

,o Arch. Gant., Jed (1896), Plate I.

41 But one note of caution should be sounded. We have, like previous writers

taken it for granted throughout that the ditch back.filled in 1344 was the same

he d.it<:h dug_in_ 1225. This seems only common sense but, in fact, direct evidence

1s lacking. Suni larly, although the Deanery garden ditch can confidently be

equat ed, in view of the pottery evidence, with that be.ck-filled in 1344 the date

when it was first dug ce,nnot be closely .fixed. '

41 Arch. Cant., x.xi (1895), Plate I.

78

P1.,\TE J

[foe, p. ,

l?LATE HA

Pholo: R. G. Foorcl

A. 'Arch of Construction' in fourteenU1-century Eust \Vall.

PLATE llB

Pholh: C. R. F/ig/1/

.B. Roman North 'Wall showing Conduit.

PLA'l'E Ill

Photo: I' . .J. '/'tsler

A. :Sqt1t.ll'ecl fttcing Stone on outside of' Ro111un Wull.

Photo: P . ./, Test,r

B. Coursed Rubble l'ocing on tho inside of tho Roman Wall.

PLATE IV

Photo: R. G. Foord

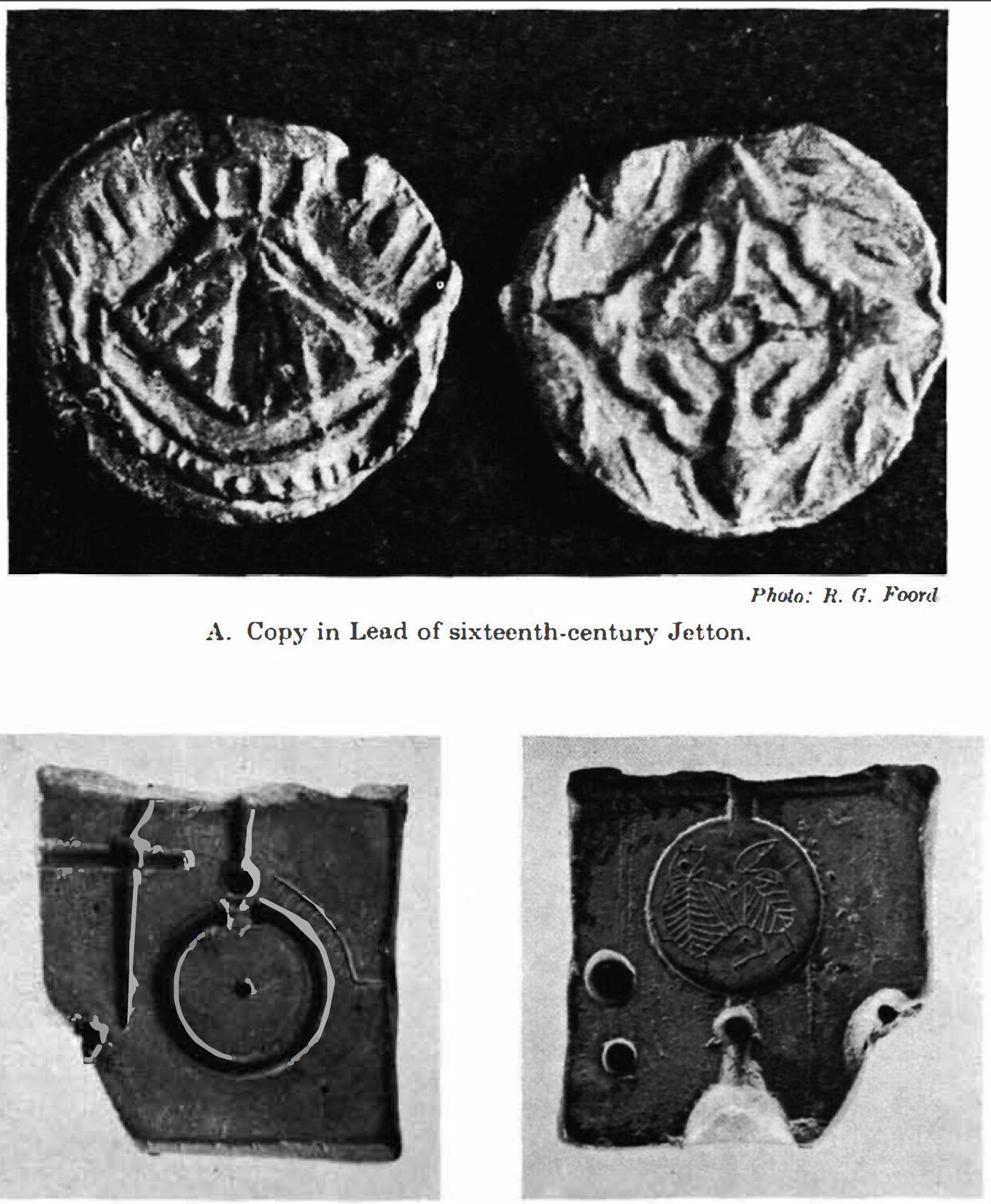

A. Copy in Lead of sixteenth-century Jetton.

.{,·'- .

I ',') ,' ,

.•, (' /,

B. Stone Mould for casting Buckle and Trinket.

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DE.FENCES OF ROCHESTER

latter case it can reasonably be equated with the south edge of the 1225

Ditch and this is supported by the fact that the filling, shown as gravel

and brick-earth, is the same as was found further east.

(2) The heavy buttressing of the south side of the Refectory, where

no less than seven buttresses project for some 6 ft., can hardly be part of

Bishop Ernulf's original building. Perhaps they date from Bishop

Haroo de Hethe's rebuilding in 1336, when the ditch would still have

been open. (Indeed it seems quite possible that the rebuilding was

necessary because the Refectory was tending to slip into the ditch.)

On this assumption the 1225 Ditch would link up at Southgate with

the ditch a.round the Castle. The street leading to St. Margaret's must

have been carried across it by a causeway, or possibly a bridge, and it

then swerv-ed sharply eastwards around Boley Hill, an earthwork south

of the Castle which, on present evidence, seems also of thirteenthcentury

da.te.42

If our interpretation of the medieval wall underlying the pavement

at Northgate is correct, then this gate was rebuilt during the second half

of the century. Otherwise there is no reason to suppose that there were

any other alterations to the rest of the circuit.

F. Fourteenth century. It is this period that presents the greatest

problems. It is common ground that in 1344 the monks were granted a

charter empowering them to fill in the 1225 Ditch from Eastgate 'to the

gate of the said Prior' and to take over its site: our excavations have

shown the ditoh was in fact so filled (see pp. 61-2 above). The width

known from documentary evidence agrees well enough with that of the

ditch outside the east wall and the length with the distance a.long the

Roman wall from Eastga.te to Southgate: the 'gate of the said Prior' may

be Southgate or a gate nearby leading into the preoinct (it cannot have

been on the site of the present Prior's Gate, as both Canon Livett and

St. John Hope supposed).4'3

In return for this concession the monks were to build a new wall

and dig a new ditch further south. The ditch which still exists, extending

the line of the previous one on the east and curving around a new

south-east angle westwards for about 400 ft., can safely be identified

with this 1844 Ditch. It is clear, too, that the old ditch was largely backfilled

with spoil taken from the new and it is even possible to trace the

progress of the work, which proceeded from east to west. The tip-lines

near the east wall which slope to the west show that to the south of the

old south-east angle a large bank of earth was first thrown across the

line of the 1226 Ditch, in order to delimit that part of it which was now

obsolete (cf. Cuttings J.Q). After that, filling proceeded directly from

the south and the tip-lines slope to the north or north-west. The ground

, Arch. Cant., lxxiv (1960), 197-8.

0 .Arch. Cant., xxi (1896), 63, 8Jld .xxiv (1900), 21.

79

ROMA.i.'i AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

inside the wall was levelled off at the same time, producing the horizon

already noted in the Cuttings A and 0, and approximately 250 ft. of the

east end of the Roman south wall was demolished, as indicated by the

dumps of mortar debris underlying the back-fill in Cuttings Band D.

The new wall was evidently intended to run along the strip of

undisturbed ground between the two ditches--Qn the line laid down on

Canon Livett's plan, parallel with the Roman wall and about 120 ft.

from it. This was clearly started from the west end. The wall running

westwards from Prior's Gate, intact at least until 1720,44 but now

la,rgely demolished except for the fragment mentioned on p. 56 above,

is on the line and in all probability belonged to it. Prior's Gate itself is

probably later, but the soar left on its eastern. face suggests that the

wall continued some way in that direction. Contemporary with this

work was the construction of the wall along the south side of the High

Street in accordance with the charter of 1345.45 It has been located

opposite the choir of the Cathedral in 188746 and again i n 1960 in the

cellar of No. 88, High Street.47

It is, however, abundantly clear that the work was never completed.

The eastern section of the wall which should have been apparent

(a) in the foundation trenches of the new Deanery, (b) in Cutting F,

(c) in Cutting H, and (d) in Cuttings L-M, was simply not there. The

ditch also seems to have come to a premature end after about 400 ft.

just ea.et of the end of :Minor Canon Row (see p. 75, above). It is

reasonable to suppose it was the Black Death of 1348-49 that interrupted

the work.

The next development was the abandonment of the unfinished

ditch and wall and the extension of the walled area to the south to

include the site of the 1344 Ditch and a strip of land beyond it. The new

wall ra.n southwards a.cross the line of both ditches (piers being sunk

through the 'fill' as was observed in Cuttings J a.nd -K) for some 325 ft.,

to a oiroular bastion and then turned westward for about 680 ft. (This

is Canon Livett's 'post-1344' Wall.) The west wall of this enclosure was

intact in the eighteenth century but its exact line is now lost; it

returned to join the unfinished wall previously mentioned a little to

the west of the present Prior's Gate which may itself be contemporary

with it (Fig. 1).

Whether this extension was ever authorized or whether the king

ever complained that the monks had failed to carry out in full their

share of the undertaking will probably never be known; nor is it possible

to assign an exact date to the work which may well be of more than one

period, as the east wall at least is certainly a complex structure. There

« Thorpe,. Regi8trum Rcffen.se, 552.

45 Arch.. Cant., xxiv (1900}, 23.

•• A.rah. Oam., xviii (1889), 201.

7 Unpublished. Information lcindly supplied by Mr. R. E. Chaplin, B.Sc.

80

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

a.re, however, two indications of a possible date which are worth

noting. The first is documentary: John Sheppey, the Prior (1333-51),

claimed in a petition to the Pope,48 that among other good works he

had 'enclosed the whole (priory) with a strong wall'; thls obviously

relates to the two charters of 1344 and 1345 already mentioned, but in

view of the established fact that the 1344 Wall was abandoned unfinished,

Prior John's claim might mean that the farther 'post 1344'

extension was completed by 1350. The seoond po.int is that, as already

noted (see pp. 67-8above), the building technique of the eastern city wall

where it crosses the thirteenth-century ditch is identical with that of

the east curtain-wall of the Castle known to have been built by Prior

John of Hartiip in 1368. In view of these points and the probability

that the southern defences would not have been left for long in such

disarray, it may well be conjectured that this final phase was completed

during the third quarter of the fourteenth century.

THE FINDS*

I. PO'l'T:ElW

(i) Romano-British

By A. P. DETSICAS, M.A., F.S.A.

Abbreviations and References

Oamulodunum C. F. C. Hawkes and M. R. Hull, Oamulodunum,

Oxford, 1947

Oanterbury Sheppard Frere, 'Canterbury Excavations, Summer,

1946', Arch. Gant., lxviii (1954), 101-43.

OGP J. A. Stanfield and Grace Simpson, Central Gauli8h

Potter8, London, U)58.

Cobham P. J. Tester, 'The Roman Villa in Cobham Park,

near Rochester', Arch. Gant., lxxvi (1961), 88-

109.

Colchester M. R. Hull, The Roman Potters' Kilns of Colchester,

Oxford, 1963.

D. J. Dechelette, Les VaseB ceramiques ornes de la

Gaule romaine, ii, Paris, 1904.

Dover L. Murray Threipland and K. A. Steer, 'Excavations

in Dover, 1945-1947', Arch. Oam., l:xiv

(1951), 130-49.

Gillam J .. P. Gillam, 'Types of Roman Coarse Pottery

Vessels in Northern Britain', AA', xxv (1957),

1-40.

Greenhithe A. P. Detsioa.s, 'An Iron Age and Rornano-British

Site at Stone Castle Quarry, Greenhithe', Arch.

Gant., lxxi (1966), 136-90.

4; Cat. Papal Pet. 1, 192 and .217, cited by R. C. Fowler, V.O.B. Kent, ii 123

The flnda have been deposited at the Eastgate House Museum, Rohesr.

81

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

J.W.

Leicester

Lu.

Lulling stone

o.

Ospringe

Rich.borough I-IV

Southwark

Su:arling

Winchester

AA'

Arch.Oant.

P. J. Tester a.nd J. E, L. Caiger, 'Excavations on

the Site of a Romano-British Sett.lement in. Joyden's

Wood, near Bex ley', Arch. Oant., Ixviii

(1954), 167-83.

K. M. Kenyon, Excavaftion8 at the J e'UR'Y Wall Site,•

Leicester, Oxford, 1948.

W. Ludowici, Katalog V, Stempel, Nannen, und

Bilder romischer Topf er aus meinen A usgralJungen

in Rheinzabern, 1901-1914, Jockgrim, 1927.

G. W. Mea.tes, 'The Lullingstone Roman Villa',

Arch. Oant., lxvi (1953), 15-36.

F. Oswald, Index of Figure-types on TerraSigiUata,

Liverpool, 1936-37.

W. Whiting, W. Hawley and T. May, Report on the

]jJxcavaftion of the Roman Cemetery at Ospringe,

Kent, 0:lrl'ord, 1931.

J. :P. Bushe-Fox, Excavafli.ons of the Roman Fort at

Richborough, Reports I-IV, Oxford, 1926-49.

K. M. Kenyon, Excavations in Southwark, 1959.

J. :P. Bushe-Fox, Excavation of the Late-Celtic Urn,.

field at Su:arling, Kent, Oxford, 1925.

B. Cunliffe, Winchester Excavations, 1949-1960,

Winchester, 1964.

Archreologia Aeliaria, Fourth Series.

Archc.eologia Oantia!na.

Coarse Wares {Figs. 13-16)

The coarse pottery discussed in this report is a small portion of the

wares recovered in the various cuttings, and a still smaller selection is

illustrated; wherever possible reference is being made to such wares in

published reports. Pa.ate is used to denote the core of the vessel, and

fa.bric to describe the finished vessel as for texture and colour.

Northgate B, Section o-p, Layer 12.

1. Dish in grey-brown fabric and grey paste, burnished (Oolchester

40B, post A.D. 120; Greenhithe 189, A.D. 120-150; Ospringe 28; Leicester,

fig. 20, no. 3, Antonine).

2. Dish in grey fabric and light grey paste (Oolche.ster 38, .A..D. 120-

400; Southwark, fig. 15, no. 3, Antonine).

3. Dish in grey fabric and sandy paste, rimless, but with a. cordon

above the lattice decoration (Gillam 234, A..D. 140-200; Greenhithe 168,

A.D. 120-150).

4. Dish in grey fabric and light grey paste; smaller but closely

similar to no. 1, above.

5. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (Oo"lchester 40A, mthout

wavy-line decoration, poat .A.D. 120; Ospringe 47, etc.; J. W., fig. 5, no.

29, Antonine; Lullingstone 115, Antonina).

82

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

FIG, 13. (¼)

83

ROMAN AND MEDmVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

FIG. 14. (¼)

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

I

(½)

r1 ,r ' i,,r - jl , r I l 1'

I\ 1 I I

t- I \-i1J :: :: '','

1I! • (d;

60-

.

. , ii• '.

(¼)

FIG. 15.

85

L-U

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

6. Dish in light brown fa.bric and grey paste, burnished ( Ospringe,

304, 364; J. W., fig. 5, no. 30, .Antonina).

7. Dish in grey-brown fabric and grey paste, burnished (Southwark,

fig. 24, no. 8; Lei.cester, fig. 20, no. 1, post A.D. 150; Oobham, fig. 5, no. 26,

post A.D. 150).

8. Dish in grey fa.bric and paste, similar to nos. 1 and 4, above.

9. Dish in grey-black, smooth fabric and grey pa-ate, with traces of

polishing, imitating samian Forms 18 or Lu. Sb (Colchester 310, post

A.D. 140; Riclworough III, 235, A.D. 80-120; Leicester, fig. 38, no. 2,

Trajanic).

10. Necked jar in grey fabric and grey, sandy paste, burnished

around the rim and neck (Southwark, fig. 16, no. 1, second century A..D.).

11. Jar in grey fabric and light grey, shell-gritted paste, with a

pronounced cordon round the neck of the vessel; this may well belong

to the series of cordoned jars discussed in Greenhithe (q.v.) and dated

to the second century A.D.

12. Bead-rim jar in grey sandy fabric and paste (Greenhithe 219,

222, A.D. 120-150; Southwark, fig. 17, no. 14, second century A.D.).

13. Dish in grey-black, smooth fabric and grey paste, with a rather

flattened rim and traces of polishing, probably in imitation of samian

Form 27 (Riclworough Ill, 226, A.D. 80-120), although the outline of the

vessel suggests a shape less rounded than the samian prototype.

14. Necked jar in grey fa.bric and paste, burnished (cf. Ospringe 57,

ll0).

15. Necked jar in grey-black fabric and grey paste (of. Ospringe 6,

51, etc.) .

.Also from this layer: Dish in grey fabric and pa.ate, burnished

(Ookhester 40A or B, post A.J>. 120); another dish, closely similar to the

preceding vessel; cavetto-riro jar in grey fabric and paste, with bur•

nished rim (Gillam 116, A.D. 125-150; Colchester 278, .A.D. 100-200;

G-reenhithe 126, A.D. 120-150); another cavetto-rim jar, similar to the

previous one; dish in light-brown fabric and paste, burnished (Cokhester

38, post A.D. 120; Southwark, fig. 15, no. 6, Antonine); 'poppy-head'

beaker in grey fabric and paste (Greenhithe 192, A.D. 120-150); cordoned

jar in grey fabric and burnished rim (probably Greenhithe 234, A.D.

120-150); cavetto-rim jar in light grey fabric and burnished rim {similar

to Greenhithe 233, A.D. 120-150); jar in grey fabric with a rolled rim

{similar to Ookhester 268A, A.D. 100-250); dish with recurved rim in

briok-red fabric and grey paste (Canterbury, fig. 8, nos. 68 and 79, A.D.

100-150); fragments of a colour-coated, folded beaker in cream paste

and grey-black slip, with faint traces ofrouletting (probably similar to

Colchester 406, late-second to early-third century A.D.); a. fragment from

the base of another colour-coated beaker in light-brown fabric and

white paste (post A.D. 140); large cavetto-rim jar with a wide, burnished

86

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

band below the neck a,nd burnished lattice decoration (Cokhe,st,e1· 279B,

A.D. 200-350; Greenhithe 233, A.D. 120-150).

Chronologically, the most significant factor is the presence in this

deposit of sherds from two colour-coated vessels, providing a, secure

terminus post quem certainly not earlier than A.D. 140, scarcely earlier

than A.D. 150.48°' The majority of the pottery found in this la.yer consists

of vessels in the tYPical Antonine black-burnished fabric, whether as

dishes or jars, pa.raUeled by the Colchester and Greenhithe vessels; the

latter, though dated in their own context to c. A.D. 150, undoubtedly

remained in use much later, certainly at least as late as c. A.D. 170. It

would seem, therefore, almost certain that, on balance, this layer cannot

be dated much earlier than the last quarter of the second century

A.D., a dating further supported by the samian ware (Fig. 15, nos. 1-4)

found in the same context. Dating: c. A.D. 170-190.

Gutting C, Section a-b, Layer 13.

16. Small jar in grey fabric and paste, polished and decorated with

dots applied en barbotine; no exact parallel was found as to the shape of

this vessel, but vessels with similar decoration are well known (Colchester

122, A.D. 150-350; Greenhithe 142, A.D. 90-120; RichJJorough III, 278,

A.D. 70-100; Lullingstone 137, .Antonine; Leicester, fig. 27, no. 23, A.D.

80-120, and fig. 42, no. 45, A.D. 125-130).

17. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (Colchester 37, A.D. 70-

170; Greenhithe 169, A.D. 120-150).

Also from this layer: Fragment ofrough-ca.st beaker (post A.D. 150);

cordoned ja.r, with burnished lattice decoration below the cordon,

probably similar to the Greenlithe (q.v.) series of such vessels (lateAntonine).

Dating: c • .A.D. 150-175.

Northgate B, Section o-p, Layer 16.

18. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (G7eenhithe 180, A.D.

120-150; Colchester 87, .A..D. 70-170).

Also from this layer: Oavetto-rim jar in grey fabric and paste,

burnished (of. Gillam 140, A.D. 180-270; Oolchest,e,r 278, A.D. 100-200;

Southwark, fig. 21, no. 24, Trajan-Ha.dria.nic). The pottery found in this

la.yer falls within the same chronological limits as that recovered in

Layer 12. Dating: c. A.D. 170-190.

Gutting 0, Section a-b, Layer 1'1.

19. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (Greenhithe 182,

.A..D. 120-150; Oolchest,er 37, A.D. 70-170).

,11a It is worth noting that a ooin of Marcus Aw·elius was found in the wallbank

nearby in an excavation in 1967.

87

lO

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

Also from this layer: Rim-fragment from a small-necked jar in grey

fabric and paste (of. Southwark, fig. 22, no. 7, A.D. 100-160); various

scraps of storage jars in shell-gritted paste (of. Greenhithe, 202, 204-5,

A.D. 120-150). Dating: c. A.D. 150-175.

Cutting B, Section c-d, Pit intru.sive in Layer 10.

20. Cordoned jar in grey fabric and paste, with a cordon immediately

below the rim and another round the neck; burnished decoration

of trellis (cf. Oankrbury, fig. 12, no. Ill, without decoration and rim

missing, A.D. 100-120; Richborou-gh II, A.D. 80-120, and III, 274:, A.D.

80-120, but with different rims).

21. Jar in brown fabric and paste, faintly rilled (Leicester, fig. 35,

no. 18, Flavian). Dating: e. A.D. 80-120.

Cutting 0, Section a-b, Layer 18.

22. Cordoned jar in grey-brown fa.brio and grey, sandy paste

(Greenhithe 155-6, 158, etc. A.D. 120-150).

23. Bead-rim je.r in grey fabric an.d paste, sandy (Greenhithe 216,

A.D. 120-150).

24. Flagon in cream fabric and grey paste, with white slip on

external surface (cf. Ospringe 522).

Also from this layer: Fragments of shell-gritted storage jars (second

century A.D.). Dating: o. A.D. 150-175.

Cutting B, Section c-d, Layer 8.

25. Bead-rim jar in grey fabric and shell-gritted paste (Greenhithe

88, 99 and 138, A.D. 120-150). Though the material recovered in this

la.yer was slight, it is quite clear from the evidence of other layers that

no chronological distinction can be established between those deposits

and this layer. Dating: c. A.D. 170-190.

Gutting 0, early Gully Filling continuous with Gutting B, Section c-il,,

Layer 10.

26. Storage jar in light brown fabric and paste, with a. double

cordon below the rim; probably hand-made (Leicester, fig. 36, no. 26,

Claudius-Nero). The filling of this gully supports the evidence mentioned

above (p. 59) of first-century A.D. activity, but the material

available is too scant to allow for more than a genera.Ida.ting of c. A.D.

50-75.

Cutting A, Section e1, Layer 8.

27. Mortarium fragment49 in fine cream fabric with thick pink core;

•0 Notes on the mortaria. were kindly provided by :Mrs. K. F. Hartley, B.A.

88

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

a few flint grits survive. The broken herringbone stamp can be identified

as one used at the Colchester kilns, and as one of the Colchester dies

most commonly attested. on other sites, particularly Antonina sites in

Scotland (Ookhester, fig. 60, no. 30, and pp. 114-16; ..A.D. 150-190).

28. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished and probably decorated

with a lattice which has now worn off (cf. Greenhithe 176, A.D. 120-150;

J. W., fig. 5, no. 28, Antonina).

29. Dish in grey fabric and paste (cf. Greenhithe 181, A.D. 120-150;

Colchester 37, A.D. 70-170; Gillam 219, A.D. 125-150; Leicester, fig. 19,

no. 3, A.D. 125/30-200; Southwark, fig. 15, no, 2, second century A.D.).

30. Jar in grey fabric and paste, burnished.

Also from this layer: Fragments of three storage vessels in shellgritted

paste (Greenhithe 202 and 205, ..A.D. 120-150); fragment of a

cavetto-rim in grey fabric and paste, burnished over rim (Colchester 278,

second century .A..n.). Dating: c. A.D. 170-190.

Culling 0, Section a-b, Layers 14 and 15.

31. Dish in grey-brown, burnished fabric and grey paste (GreenMthe

187, 239, A.D. 120-150; Gillam 310, .A..D. 170-210).

32. Dish in grey fabric and light grey sandy paste, burnished

(Cokhester 37, A.D. 70-170; Greenhithe, 180-1, A.D. 120-150).

33. Jar in grey, smooth fabric and grey paste, rouletted decoration

(late-Antonine).

34. Jar in brown fabric and grey, sandy paste, with traces of

burnishing on the high shoulder and rim, rilled (close to Southwark,

fig. 20, no. 3, A.D. 100-120).

35. Jar in brown fabric and paste, with some shell-grit (near

Greenhithe 118, A.D. 120-150).

Also from this layer: Carinated beaker in grey, smooth fabric and

paste (cf. Riclworough III, 291-2, .A..D. 80-120); rim fragment of 'poppy.

head' beaker, Antonine; storage jar in light brown, shell-gritted paste

(Southwark, fig. 18, no 2, second century A.D.); jar in brown fabric and

shell-gritted paste (Antonine). Dating: c. A.D. 150-175.

Gutting A, Section e-f, Layer 7.

36. Mortarium fragment in very hard, dark pink-brown fabric with

near black core, closely reminiscent of tile in texture. This piece is

certainly not from any of the major potteries producing mortaria, but

there is some evidence that such a fabric could have been made in Kent

and origin there seems most likely. A Flavian date would not be impossible

for this piece though it could be second-century.

37. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (Greenhithe 182,

A.D. 120-150; Ookhester 37, .A..D. 70-170).

89

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

38. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (Southwark, fig. 15, no ..

5, late-second to early-third century A.D.; 08pringe 5, etc.; Oolchester 38,

post A.D. 120; J. W., fig. 5, no. 31, .Antorune).

39. Dish in grey fabric and paste, burnished (Ookhester 37, .A.D. 70-

170; Greenhithe 58, A.D. 150-200; Riolworough Ill, 46, Antonine).

Also from this layer: Fragment from a storage jar in brown, shellgritted

paste, with thumb-nail decoration (Greenhitke 202, A.D. 120-

150). Dating: c . .A.D. 170-190.

Gutting A, Section e-f, Layer 9.

40. Jar in grey fa.brio and paste with shell-grit, probably handmade

(of. Colchester, fig. 73, no. 22).

41. Dish in dark grey fabric and grey sandy paste, burnished on the

inner and outer surfaces (of. Greenhitke 170, A.D. 120-150; Gillam 327,

A..D. 130-180; Leicesur, fig. 49, no. 5, to .A.D. 220).

42. Probably a dish, in drab grey fabric and light grey paste, with

rouletting (of. Richborough m, 212, A.D. 75-100).

Also from this layer: Fragments from a storage jar in light brown

fabric and shell-gritted paste (second century A.D.). Dating of this layer

can only be very appro;ximate as the pottery deposited in it is not only

very fragmentary but also covers a. fairly wide range of time; this is

particularly true of the samian ware. On balance, a date in the third

quarter of the second century .A.D. is not unlikely.

Gutting A, Section e-f, Layer 5.

43. Necked jar in grey fabric and paste (Soutliwark, fig. 16, no. 3,

second century A.n.; Leicester, fig. 38, no. 20, Trajanic; Winchester,

fig. 17, no. 29, A.D. 43-140).

44. Cordoned jar in grey sandy fabric and paste, with one cordon

below the rim.

45. Jar in grey-brown fa.bric and brown, sandy paste.

Also from this layer: Dish in dark grey fabric and paste, burnished

(Greenhithe 184, A.D. 120-150; Colchester 37, A.D. 70-170); a. fragment

from the base of a vessel in shell-gritted paste (second century A.D.).

Dating: post c. A.D. 170.

Gutting A, Section e-f, Layer 6.

46. Jar in light brown fabric and grey, sandy paste, with a rolled

rim and traces of soot internally; perhaps hand-made (cf. Leicester,

fig. 24, no. 20, A.D. 95-200 and later).

47. Mortarium fragment in fine, yellowish cream fabric with whitish

trituration grit. This fabric and grit was used both in the extensive

potteries at Colchester, and at Canterbury in Kent. The form is

certainly second-century, probably earlier than A.D. 170.

90

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

Also from this layer: Dish in grey fabric, burnished (Colchester 37,

A.D. 70-170; Greenhithe 180, A.D. 120-150); mortarium fragment in finetextured,

pinkish cream fabric with a trace of grey in the core-this is a

difficult mortarium to assess; its place of manufacture is uncertain but

Kent would be a possibility. It was probably made within the period

A.D. 90-150. Dating: c. A.D. 170-190.

Gutting G-H, Section k-l, Layer 8.

48. Carinated beaker in grey, smooth fabric and paste (Rickborough,

I, 75-77, first-second century A.D.; Greenhitke 144, A.D. 120-150).

49. Dish in dark grey fabric and sandy paste, burnished (Greenhithe

187, A.D. 120-150; Gillam 310, A.D. 170-210; Cobham, fig. 3, no. 14,

A.D. 70-180; Dover, fig. 9, no. 8, late-first to second century A.D.).

50. Dish in grey, smooth fabric and paste, probably in imitation of

samian Form Lu. Sb (RicnborOU{lh m, 235, A.D. 80-120; Colchester 310,

post A.D. 140).

51. Dish in grey smooth fabric and paste, imitating samian Form

Lu. Sb, a.s above.

52. Dish in grey smooth fa.brio, burnished, imitation of samian

Form Lu. Sb (RickborOU{lh III, 235, A.D. 80-120; Colchester 310, post

A.D. 140; Leicester, fig. 38, no. 2, Trajanic).

53. Dish in brown fabric and paste, rather coarse and with a groove

at the top of the vessel: probably hand-made.

54. Bead-rim jar in grey fabric and sandy paste (Greenhithe 222,

A.D. 120-150),

55. Bead-rim jar in reddish brown fabric and grey paste with shellgrit

(Southwark, fig. 17, no. 15, second century A.D.).

Also from this layer: Fragment from a carinated beaker, probably

similar to no. 48, above (second century A.D.); jar in smooth grey fabric

and paste (cf. SC>Uthwark, fig. 16, no. 3, second sentury A,D.). Dating:

post c. A.D. 170.

Cutting A, Section e-f, Layer 10.

56. Necked jar in dull red paste, with yellowish cream slip. This

vessel can best be described as a. debased copy of a pedestal urn, and its

ancestry could be traced back to Swarling 3 and 9, except that the foot

of those vessels is rather different from that of the Rochester jar. The

shape of this vessel approximates Camulodunum 108 Aa and Bb, reechoed

in Colchester, :fig. 75, no. 10; its paste, however, is identical with

that often used in the manufacture of flagons (cf. Greenhithe 143,

A.D. 120-150). Typologically, this jar would seem to be one of the

earliest vessels recovered, and a date in the last quarter of the first

century A..D. would not be improbable.

91

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

Samian Ware (Fig. 15).

(a) Plain Forms. The great majority of the sherds found were too

fragmentary for the purpose of close dating but, in general, agreed

broadly with the coarse wares. Form 33 predominates in the series of

cups, Form 27 is represented by few certain fragments, and the early

Form 24 is totally lacking; likewise, in the plate forms, Form 18 is not

represented, and most pieces belong to Forms 18/31 or 31, with a fair

proportion of the late Form 3 l(Sa). Only one fragmentary stamp was

found on a cup of Form 33, and this probably reads (PISTI)LLIM.

South Gaulish samian is entirely absent.

(b) Decorated Forms. Here, too, no South Gaulish samian was

present. Forms 29 and 30 are absent, except for one or two scraps

which may belong to the latter form. All the sherds described below

were found in Northgate B, Section o-p, Layer 12, except for no. 5,

found in Cutting A, Section e-f, Layer 7.

I. Form 37. East Gaulish, in fair condition but with glaze almost

completely worn; in the style of HELENIVS of Westrndorf (K. Kiss,

A Westerndorfi Terra-Sigillata. Gyar, in Archaeologiai Ertesito, Serie III,

1946-48, Budapest, 1948). The design is enclosed by a double basal line

over which have been impressed several spiral decorative details (Kiss,

OJJ· cit., pl. VI/64), also known in use by this potter in lieu of the ovolo

(Kiss, op. cit., pl. XV/I, 3). The double half-medallion (Kiss, op. cit.,

pl. VI/80) contains one figure-type, Putto to left (0.459 = Lu. V M288)

and outside it a free-style incision in the mould simulates vine tendrils.

Dating: c. A.D. 175-200.

2. Form 37. Central Gaulish. Fair glaze. The decoration is badly

blurred as this bowl was probably made in a worn mould. The ovolo is

rather large and rounded, without a central projection, has a corded

tongue ending in a badly-blurred rosette and is enclosed by a mediumsized

bead-row border. The remnants of the decoration preserved show

a vertical bead-row border terminated by another blurred rosette,

which divides the decoration into panels: to left, Bird to right (0.2317),

though this figure-type is of such poor relief that it looks rather smaller

than Oswald's bird; to right, part of a basket with fruit (D.1069), which

has not been completely restored in the drawing as it could be

0INNAMVS's variant (OGP, pl. 158/20} of this ornament rather than

Deohelette's detail. The ovolo is ADVOCISVS's no. 1 (OGP, p. 205,

:fig. 33); this potter ha.s used a bird similar to, though larger than the

figure-type on this sherd (cf. OGP, pl. 112/3, D.1010 = 0.2316).

Dating: c. A.D. 160-190.

3. Form 37. Central Gaulish. Rather worn. A remnant of a doublebordered

ovolo with a corded tongue ending almost straight. The ovolo

roulette obviously completed its circumference of the mould at this

92

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

point and careless application has resulted in superimpression. This is

. CINNAMVS's ovolo no. 5 (OGP, p. 267, fig. 47). Dating: c. A.D. 145-190.

4. Form 37. Central Gaulish. In fair condition. A fragment from the

upper part of the decoration, with a double-bordered ovolo which has a

corded tongue ending in a swollen tip; this is probably the ovolo no. 1

ofIANVARIS II (OGP, p. 213, fig. 34). Dating: c. A.D. 150-180.

5. Form 37. Central Gaulish. In good condition. In the style of

CINNAf.fVS, with his ovolo no. 3 (OGP, p. 267, fig. 47), enclosed by a

slight wavy-line border, and part of one figure-type, Bear to left

(D.775 = 0.1619) which has been often recorded in this potter's work

(OGP, pls. 157 /7 and 159/33). Dating: c. A.D. 145-190.

(ii) Medieval (fig. 15)

By G. C. DUNNING, B.Sc., D.Lit., F.S.A.

Northgate B, Section o-p. F01J,ndation of Medieval Wall.

The pottery consists of sherds of decorated jugs of fine quality sandy

ware, belonging to five pots as follows:

57. Rim, neck and body sherds of light red ware, partly grey in the

core. The surface is light red with patchy green glaze on the neck and

body. Decorated on neck and body with broad, flat, white strips,

diamond-rouletted. The strips are vertical on the neck, curved and

branching on the body. The inner bevel of the rim has a white slip.

58. Rim and neck of jug, similar to no. 57 of grey ware with light

red surface. White slip covers the outside, the bevel of the rim and the

inside of the neck for about I inch. The neck is partly green glazed.

Decorated on neck with strips, one diamond-rouletted between two

with more irregular marks.

A body sherd probably belongs to this jug. It has a vertical diamondrouletted

strip and green glaze overall.

59. Two body sherds of grey ware, with grey to buff surface inside.

Decorated with plain, narrow, applied strips or ribs. The larger sherd

haa four strips, two vertical and two curving to the right, suggesting

panels with festoons separated by vertical lines.

60. Body sherd from below handle. Grey ware, thicker than the rest

and with harsher surface. The inside is light red, and the outside has a

thin white slip. Decorated with vertical diamond-rouletted strips. The

glaze is overall, thicker on the strips, green mottled with darker green

and brown.

61. Body sherd of thin ware, grey core and inside, thin white slip

outside. Vertical diamond-rouletted strip, and streaky green glaze

overall.

93

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

DISCUSSION

The pottery forms a consistent group comprising two main types of

jugs:

(1) Nos. 57-58. Tall slender jug!!, about 13-16 in. high. The neck

a-nd body are decorated with rouletted strips, either of white clay or

coloured by glaze. Complete jugs of this type, variously decorated with

linear and curvilinear patterns, have been found in London.5°

(2) Noa. 59-61. Shorter jugs, a.bout 12 in. high, with ovoid body.

The diamond-rouletted strips on Nos. 59-60 are ty:pical of London,51

where the narrow strips on no. 61 also occur.62 The festoon or arcade

motif is also known in other techniques in the, London region.53

The kilns which existed primarily to supply London with pottery

were situated in East Surrey, where waste heaps of the industry are

extensive. Earlswood has produced a waster with stamped and

diamond-rouletted decoration,M and the Rochester pottery was

probably made here. The products of this kiln and of the workshop of

Limpsfield,65 where the pottery is more archaic in character, have been

found at half a dozen sites in north-west Kent.66 Further east in Kent

the finds are more sca.ttered, at Rochester, Canterbury and Stonar.li7

The evidence points to a. considerable trade in East Surrey pottery to

places along the coastal part of north Kent during the second half of

the thirteenth century.

Cuttings A-D.

(iii) Medieval (figs. 16 and 17)

By P. J. TESTER, F.S.A..

The medieval pottery from these excavations is here figured and

described mainly for the evidence it affords as to the age of the contexts

from which it was recovered. Most of the material is very fragmentary

and only a small proportion lends itself to illustration. The main groups

contain examples of the well-known type of cooking pot with straighttopped

flange of marked projection, which is generally accepted as

beginning in this area towards the end of the thirteenth century and

continuing into the fourteenth. The few earlier sherds found in association

must, therefore, be regarded as rubbish survivals. Probably both

ao London M.tllleum, Medieval, Catalogue, 214, pl. bd.

ai e.g. London Museum Acc. N os. 17129 and 26665.

a2 Guildha.U Museum Aco. No. 17728. Rackham, Medieval E ngli8h Pottery,

pl. 48.

63 Med. ATch.., v, 270, fig. 72, 1.

54 Su'M'ey AToh. Ooll., xxxvii (1927), 245.

5 6 C.B.A., Exhibition of Medieval Pottery (1964), 5, No. 6.

88 Arch. Oant., lxxii (1958), 31-9.

n Deal Castle Museum.

94

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

l- - - --1 41

,64 (

)

)66

)

'6S I r (

4\: 68 69 4',o ,,

\,2 I

.. ,.1

i \

} (

11\,s

r· -----··i l \

.,BI 1 ==;-i

"Bl T. ()

fl D

'9S 8iib!

FIG. 16. (¼)

95

ROl\1AN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

/-, l8 I

I

----

t

T,

-:i --i===--=======;::,(

£ ;,-------,;::::==...--==-------=---_,,(

\94 I / L _____J ======1 196 ? 17

I

\

1---: --._,----_ -_ ---,-,c ,:· · ·7

;-------.--=::::--=====;::., "! F -

\. I ;

-- ( t I f t r-"7

). I rt::-

FIG, 17. (¼)

96

!.✓JI.

ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL DEFENCES OF ROCHESTER

the medieval bank behind the city wall in Cutting A and the filling of

the medieval ditch in the Deanery Garden were composed to some

degree of surface scraping from within the area of the defences which

would account for the mixture of sherds of different ages. In support of

this it may be mentioned that Romano-British sherds occurred as

survivals in these medieval layers in some quantity.

M:r. J. G. Hurst and Mr. S. E. Rigold have kindly discussed the

dating of Nos. 62-71 and No. 85 and their helpful comments have been

incorporated in these notes.

Gutting A (fig. 5), Swtion e-f.

Layer 3.

62, 63, 64 and 66. Rim sherds of cooking pots, probably globular

and thrown on a slow wheel. Short everted necks and plain rims. No.

62 has a facetted body indicative of knife-tooling. The ware is hard,

sandy and grey, and akin in form to East .Anglian 'Early Medieval'

ware68 but in some ways closer to Thetford ware in fabric. Evolved

wares of this general type last well into the twelfth century in East

Anglia and are normal c. 1140 at South Mimm.,, Herta. They do not

occur at Eynsford Castle, but cf. possible parallels from Canterbury.so