Kent Archaeological Society Newsletter, No. 40. Spring 1998

The Castles of Kent No.3: Rochester Castle

Introduction

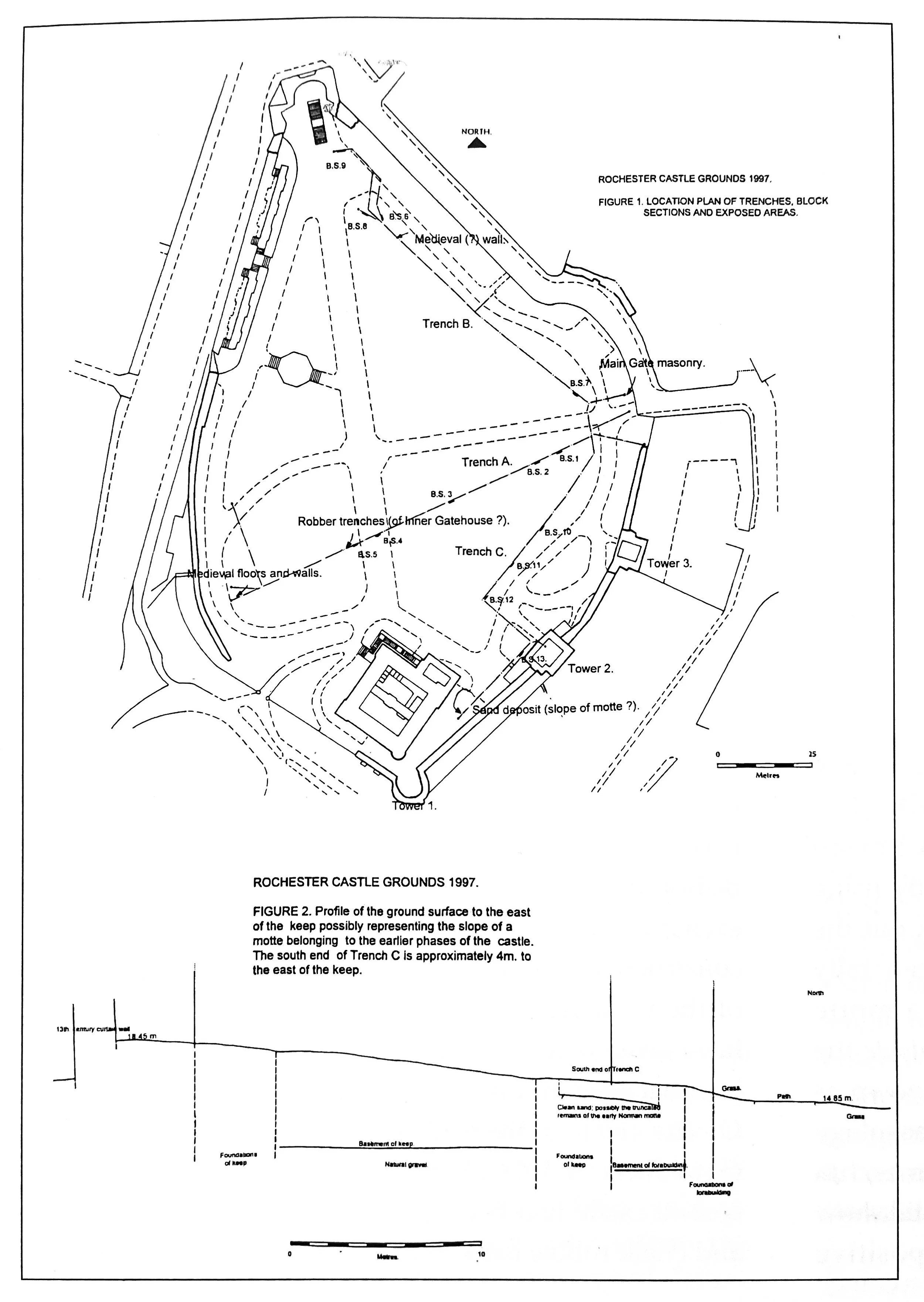

In 1997, the Canterbury Archaeological Trust undertook an archaeological watching brief at Rochester Castle while trenches were excavated for new electricity cables (Fig. 1) (Ward and Linklater 1997). Thanks are extended to Rochester upon Medway City Council for funding this archaeological work and to all those who assisted with the project.

During the post-medieval (1550-1750) and early modern (1750-1875) periods, the castle grounds were used as allotments, gardens, and, most recently, a grassed open area. Both horticulture and landscaping would mean compost, soil, and other materials being brought into the castle grounds. It was expected that there would be a build-up of about a meter over medieval deposits. As the trenches to be excavated were to be only 0.75 m deep, it was thought unlikely that significant archaeological deposits would be encountered. As is usual on archaeological sites, the expected did not happen!

Although the standing fabric has been studied in some detail (Livett 1895; Payne 1905), very little is known about the below-ground archaeology of the castle. In 1976, Colin Flight and Arthur Harrison undertook a small excavation immediately in front of the outer wall, adjacent to Epaul Lane (Flight and Harrison 1978). This important trench produced the remains of a Roman building passing below the medieval defenses. By using all the known evidence, they were able to work out the sequence of castle construction. It had been generally accepted that the first Norman castle was a motte (mound) and bailey (courtyard) constructed outside the third-century Roman town walls, on what is known as Boley Hill. This is one of the fables of local archaeology which, because it has been repeated so many times, has become 'fact' (modern Ordnance Survey maps still show this 'castle' on Boley Hill). Not a shred of positive evidence has been produced for a castle ever having existed at this position. This interpretation was accepted because it was what archaeologists 'wanted' (unfortunately this 'woolly minded' way of thinking is, if anything, on the increase within Kentish archaeology - my students take note!). If looked at in an objective manner, this fable could have been quickly dismissed. At Canterbury, London, York, Lincoln, Wareham, and other urban places, where defenses already existed, the Normans constructed castles within those circuits. If part of a pre-existing defensive area could be cordoned off, this was the easiest, quickest, and cheapest way of constructing a new fortification. Also, it would more easily dominate and defend the town. The only possible exception known to the present writer, of a castle being constructed outside of an urban center, is at Dover, but here there is the problem of even identifying the site of the late Anglo-Saxon town (Tatton Brown 1984, p.23).

The Development of the Castle

Although much detail remains hidden, the main building phases of the castle are probably known:

1. The first castle on the site would either be of the motte and bailey or ringwork type. The latter consisting of a bank, palisade, and ditch. The castle must have been in existence by 1086 for Domesday Book tells us that the Bishop of Rochester, the pre-Conquest landholder, had exchanged the site for property at Aylesford. The date of construction is more likely to be nearer 1066-72, the time of the Conquest, than later. The exchange of land may have taken place only after the contingencies of war had been satisfied and merely recognized a fait accompli.

Of the first castle, nothing can be seen today. The excavation of 1976 showed that the stone wall of the second castle had been constructed on an earlier gravel and chalk rubble bank. If the wall was being constructed from new, it would almost certainly not be constructed on an unstable bank. It is a reasonable deduction, therefore, that this bank must represent the first castle. The gravel of this bank was observed in 1976 (Flight and Harrison 1978) and again in 1995 (Ward 1995) when the so-called 'arches of construction' forming the foundation of the fourteenth-century east wall were exposed. The gravel of the earlier rampart had stuck to the underside of each arch. The base of the gravel lay directly on top of the so-called 'dark soil' layer, which was deposited after the abandonment of the Roman town. The top of the dark soil must represent the late eleventh-century ground surface; from this point to the internal apex of the arches is a height of 3.40 m. This is the minimum height of the rampart. As gravel is inherently unstable, the higher the rampart, the broader it would need to be. It also seems likely that a vertical timber or turf revetment would be necessary on the external face. As the rampart was constructed on the then ground surface, it must also mean that the slope within the late eleventh-century bailey would be completely different from that which is seen today. The chalk ridge upon which the castle stands would be narrower and slope to the east as well as to the north. Gradually the area behind the rampart has been leveled off, the build-up being over four meters deep. Well-preserved Anglo-Saxon, Roman, and Iron Age deposits may exist below this leveling.

2. Between November 1087 and May 1089, Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester, agreed to fortify the castle 'for the king in stone at his own expense', the king in question being William II (1087-99). The wording implies the presence of an earlier, timber, castle. That this stone wall was constructed on the earlier bank suggests that it was made at a time of emergency. As stronger fortifications are usually constructed as a consequence of 'events,' there is the distinct possibility that Gundulf was ordered to build the castle once the rebellion of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent, and the king's uncle, had been quashed (mid-1088). In case of further trouble, the emphasis was perhaps on speed rather than quality or stability. This castle is usually referred to as Gundulf's Castle, implying the site was back in the hands of the Bishop of Rochester, whereas in fact, it was still a royal establishment. Parts of the fabric of this structure can be seen in the outer wall on the west side of the bailey. The castle at this date may have retained an earlier motte, had a new one constructed, or have been a large walled enclosure.

3. The bailey is dominated by a classic Norman keep. This magnificent structure was built by Archbishop William de Corbeil, in or after 1127 with the permission and encouragement of Henry I (1099-1135). The king granted the custody and constableship of the castle to the archbishop and his successors.

4. After the siege of 1215, one of the few occasions in this country when a castle was taken by assault, the fortification was taken back into royal hands. The southeast tower of the keep was rebuilt, and various other repairs and alterations undertaken. In 1230-1, it was ordered that a wall be constructed in front of the keep, thereby dividing the bailey in two. What is supposed to be the eastern stub of this wall can be seen protruding from the southwest corner of Tower 2.

5. The east wall of the castle was rebuilt between 1367 and 1370 in the reign of Edward III (1327-77). As the foundations of Gundulf's wall were not seen in 1976 or 1995, they must have been of shallow depth. It seems likely that rebuilding was necessary due to the gravel rampart moving and consequently weakening the eleventh-century wall. The fourteenth-century wall may have been built on a seasonal basis, for what appear to be breaks in construction were identified in 1995. The two rectangular towers were also built at this time, although Tower 2 was preceded by an earlier structure. After the sixteenth century, the castle ceased to be of military use and passed to private owners.

The Trenches

Trench A. At each end of this trench, interesting archaeological deposits were observed. At the north, on the site of the medieval main gate, destroyed in the eighteenth century, masonry was found less than 20 cm below the modern ground surface. Although no edges of the structure were observed, the degree of preservation shows that a good plan of the gate can be recovered should the opportunity ever arise.

Two 'robber cuts,' representing the lines of destroyed walls, were observed to the south of the main modern path leading to the keep. If their alignment were continued, they would meet at a right angle. Although the trenches were backfilled with demolition material and therefore represent 'robber' trenches, their width, of 1.25 and 2.00 m, shows that a substantial structure must have existed at this point. It seems likely that this building was the inner gatehouse. Unfortunately, no trace of the dividing wall, to which the gate should have been attached, was observed during the trenching, nor in subsequent geophysical surveys undertaken across the grassed areas.

At the extreme south end of the trench, a clay floor and demolition material were observed. The deposits were not excavated, but a substantial amount of medieval pottery was recovered from the surface. From the clay floor, 97 sherds of pottery, dateable to the period 1200-1225/50, were recovered. From demolition and occupation deposits below the floor, 155 and 139 sherds were found, dating from 1175-1200/25 and 1200/25-1275, respectively. The concentration of a large amount of pottery in a small area, and a date range tending to center on the early thirteenth century, may be significant and perhaps represents the events of 1215 and subsequent rebuilding. The building represented by the clay floor would have been constructed against the outer wall and was lit by four windows overlooking the river. These four openings are usually referred to as loops implying defensive attributes, of which they have none, they are designed for letting in light.

Trench B. Only at the west end of this trench was anything of significance seen. A ragstone rubble wall foundation representing one side of a north-south aligned structure was observed. The truncation of this wall, presumably in the post-medieval period, had destroyed its associated floor deposits. Three sherds of pottery dateable to the period 1175-1225/50 were recovered. An extensive dark brown sandy gravel deposit seen at the far west end of the trench probably represents the bank of the earliest Norman castle.

Trench C. At the extreme south end of this trench, 80 cm of early modern deposits overlay a layer of sand which stretched for at least five meters northwards. This deposit respected the slope of the modern ground surface, which in this corner of the castle grounds is considerable, rising nearly four meters in a forty-meter length (Fig. 2). That the sand dips below other deposits suggests that it continues downwards at a steeper angle. It is possible that this deposit represents a Norman motte in the southeast angle of the bailey. Although sand is not a good material from which to make a mound, there is a parallel at Hastings (Barker and Barton 1977, p.88).

Conclusion=

While little actual excavation took place, the exercise gave a good archaeological insight into what can be expected should future trenching be undertaken across the castle grounds. That high-quality archaeological deposits survived so close to the surface was a surprise to all concerned, and it must be assumed that well-preserved deposits exist over the whole of the grassed area at a depth of less than a meter.

References

Barker, P.A. and Barton, K.J. 1977. Excavations at Hastings Castle 1968, The Archaeological Journal, Vol. 134, p.80-100.

Flight, C. and Harrison, A.C. 1978. Rochester Castle, 1976, Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. XCIV, p.26-60.

Livett, G.M. 1895. Medieval Rochester, Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. XXI, p.17-72.

Payne, G. 1905. The Reparation of Rochester Castle, Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. XXI, p.17-72.

Tatton Brown, I. 1984. The Towns of Kent, in Anglo-Saxon Towns in Southern England, (Ed. J. Haslam).

Ward, A. 1995. Rochester Castle Curtain Wall (unpublished archive report).

Ward, A. and Linklater, A. 1997. An Archaeological Watching Brief at Rochester Castle (unpublished archive report).

Alan Ward. Dec.1997.