Notes on Brasses Formerly Existing in Dover Castle Maidstone and Ashford Churches

Notes of Brasses Formerly Existing in Dover Castle, Maidstone, and Ashford Churches.

By Herbert L. Smith, Esq.

In the description of the Surrenden Collection of manuscripts given by the Honorary Secretary in the preceding pages, mention is made, at p. 51, of a volume of Church Notes made by Sir Edward Dering, the first baronet, in conjunction with Philipot, about the year 1630. I have the gratification of communicating to the pages of 'Archaeologia Cantiana' four specimens from this volume. The outlines here given are exact copies of the originals, and fair samples of the interesting nature of the whole collection. It is only to be regretted that these records do not extend beyond thirty-two parishes. Many of the monuments, however, here recorded, have either wholly passed away, or have suffered great mutilation since Sir Edward's trickings were originally made. A large number of the heraldic memorials no longer exist, and in one instance, viz. that of the ancient church in Dover Castle, nothing remains but roofless crumbling walls.

I have copied the Dover Brass in exact facsimile of the original, without that reduction in size which was found necessary to adapt the other three outlines for the pages of this work. Lyon, in his history of Dover Castle, gives a very rough and unsatisfactory sketch, more like that of an effigy than a brass, being without any of the decorations, canopy, etc. In describing it he appears to copy Dering's remarks verbatim, and had probably seen our manuscript; for, in another place he refers to Records "in possession of a gentleman whose ancestors filled a high office in Dover Castle." From which we may gather that he had been allowed access to the Surrenden muniments. He also gives the result of researches made in 1776, when the gravestone was exhumed, and displayed the extent of its original ornamentation, by the number and variety of its chasings. This stone, he says, was erroneously described by Weaver as of marble, whereas it was of a coarse grit, full of marine petrifactions. No doubt Weaver meant the favourite Bethersden marble, so extensively used in early periods in our county. So little regard was paid to these remains, that, although at a greater depth another large stone was found covering a slightly plastered grave, in which a few bones still remained, the soldiers were permitted to break up this venerable relic, and to use it for various purposes.

The drawing will show the original condition of this beautiful brass, and is, I believe, the only record of it, in its perfect state, now extant. This Sir Robert Astone was son of Sir Robert of Ashton-under-Line, and filled many honourable offices, such as Admiral of the Narrow Seas, Justice of Ireland, Treasurer of the Exchequer, and Chamberlain to Edward III., by whom he was also appointed to be an Executor of his Will. At the foot of the tracing of the brass, Dering notes thus:--"On a flat gravestone, right before the high altar, this figure and inscription to Sr Robert Astone;" and below that, this note:--"The circumscription of the great bell here, and weighing 3000 lb. weight,--and which was the gift of that Sr Robert Astone,--hath every letter fair and curiously cast, and each crowned with a ducal crown. 'Dominus Robertus de Astone, miles, me fecit fieri, A. quarto R. Ricardi scdi G.' Lower than this, in small letters, was cast--'STEPHEN NORTON OF KENT ME MADE IN GOD INTENT.'

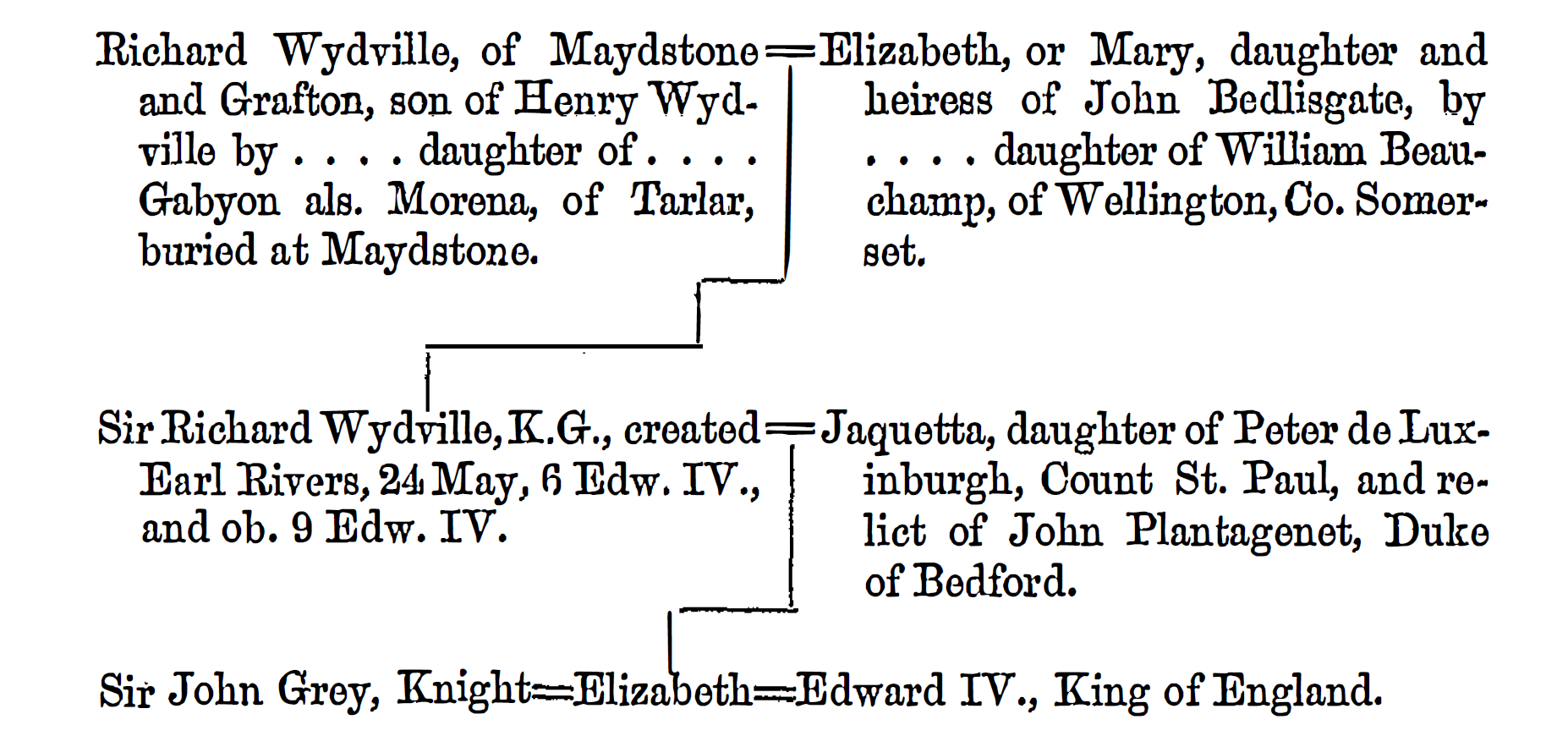

In Maidstone church, the large stone on which was the figure of Woodville, (though now lying level with the pavement,) in the days of Dering, covered an altar-tomb, and had then all its brasses complete. Not one of these now remains, but the form and number of the chasings sufficiently identify it as the one represented by Dering. The following pedigraic sketch,--for which I am indebted to T. W. King, Esq., York Herald,--is from Vincent's Collections in the College of Arms, B. 2. 253, and it enables us to identify the escutcheons as those of Richard Wydville, of the Mote, in Maidstone, viz. first and third shield, quarterly, first and fourth Wydville, second and third Gabyon; second shield, quarterly, first and fourth Bedlesgate, second and third Beauchamp; fourth shield, the first impaling the second.

The outline of the canopied altar-tomb in Maidstone church, hesitatingly assigned by Dering to Courtenay, represents a monument about which considerable uncertainty has existed.

Courtenay lived much at Maidstone, and founded the College there; he was also a great benefactor to the church of Maidstone. In his will, made some time before his death, he had bequeathed that his body should be buried in the nave of Exeter cathedral, where the remains of his father and mother rested; but during his last illness he altered his intentions, and added a codicil directing that his remains should be interred in the collegiate church of Maidstone, not esteeming himself worthy to repose in the metropolitan church of Canterbury. At the time of his death, July 31st, 1396, King Richard II. was at Canterbury, and being informed of that event, gave orders that the obsequies should take place there; and his body was accordingly removed to Canterbury for that purpose on the 4th of August, where, according to a small old Obituary in the Registry of Canterbury, he was interred in the presence of the King, nobility, clergy, and ten thousand people.

If this be a correct historical outline, we may reasonably conclude that Courtenay's remains lie at Canterbury, beneath the alabaster monument there raised to his memory, though without an inscription. A tomb, however, had been prepared for him at Maidstone. Weaver gives us the Latin hexameter epitaph which was inscribed upon it; it was probably from the pen of Wotton; and expressly asserts that the Archbishop had caused the tomb to be built "ab imo," and had desired to be buried therein: and there still exists in the pavement of the chancel a large slab eleven feet five inches long by four feet two and a half inches wide, which manifestly demonstrates, by the still existing indentations, that an Archbishop's brass, with canopy and other ornaments, once occupied its surface. The Rev. Beale Poste has kindly informed me that until the commencement of the present century, it formed the tablet of an altar-tomb, but the loss of the brasses no doubt occurred anterior to Dering's visit, or he would have noted them. On this altar-tomb, probably, Courtenay's body lay in state immediately after his death, with the full intention that his obsequies would be there completed as by himself directed, all things proceeding regularly for that end, and there commenced the fifteen thousand masses and two thousand matins he had directed should be offered up for the repose of his soul: but, owing to the King's directions, the tomb itself remained a mere cenotaph.

But the question still recurs, How can we prove the canopied monument so long associated with Courtenay, to be Wotton's, and not Courtenay's? By referring to the Will of Wotton, in the Registry of Lambeth Palace, 'Chichele,' p. 309, we find Wotton thus providing for his burial--"Presentando corpus meum ecclesiastice sepulture, videlicet in ecclesia collegiata de Maydeston antedicta, in loco destinato, ante altare sancti Thome martiris, in ala australi dicte ecclesie collegiate." Hence, it is evident that he had fixed upon the identical spot on which the monument now stands, as that where he wished his body to be buried; the place therefore could not have been previously occupied by either cenotaph or tomb. The confusion seems to have arisen from the various escutcheons displaying so prominently the arms of Wotton's great patron, Courtenay. The canopy still exhibits the following coats: first, the arms of the college of which Wotton was the first master, azure three bars gemelles, or; second, those of Wotton's first patron, Courtenay, impaling the See; third, Arundel, Courtenay's successor, impaling the See; lastly, Christchurch, Canterbury. The circumstance that the arms of Arundel, Courtenay's successor, occur on the canopy, at once proves that the monument could not be Courtenay's, but that the two archbishops stand in nearly equal relation as patrons of him whose tomb their arms decorate. The brass portrait, according to Dering's drawing, was that of a simple priest, having at his head on one side, the arms of Courtenay; on the other, the same arms impaling the See of Canterbury. I have not been able to discover that Wotton had any coat or was entitled to bear arms, which circumstance may account for his using the arms of his patrons.

It may be interesting in a future volume to give the wills of Courtenay and Wotton more at large, as they contain many curious illustrative details.

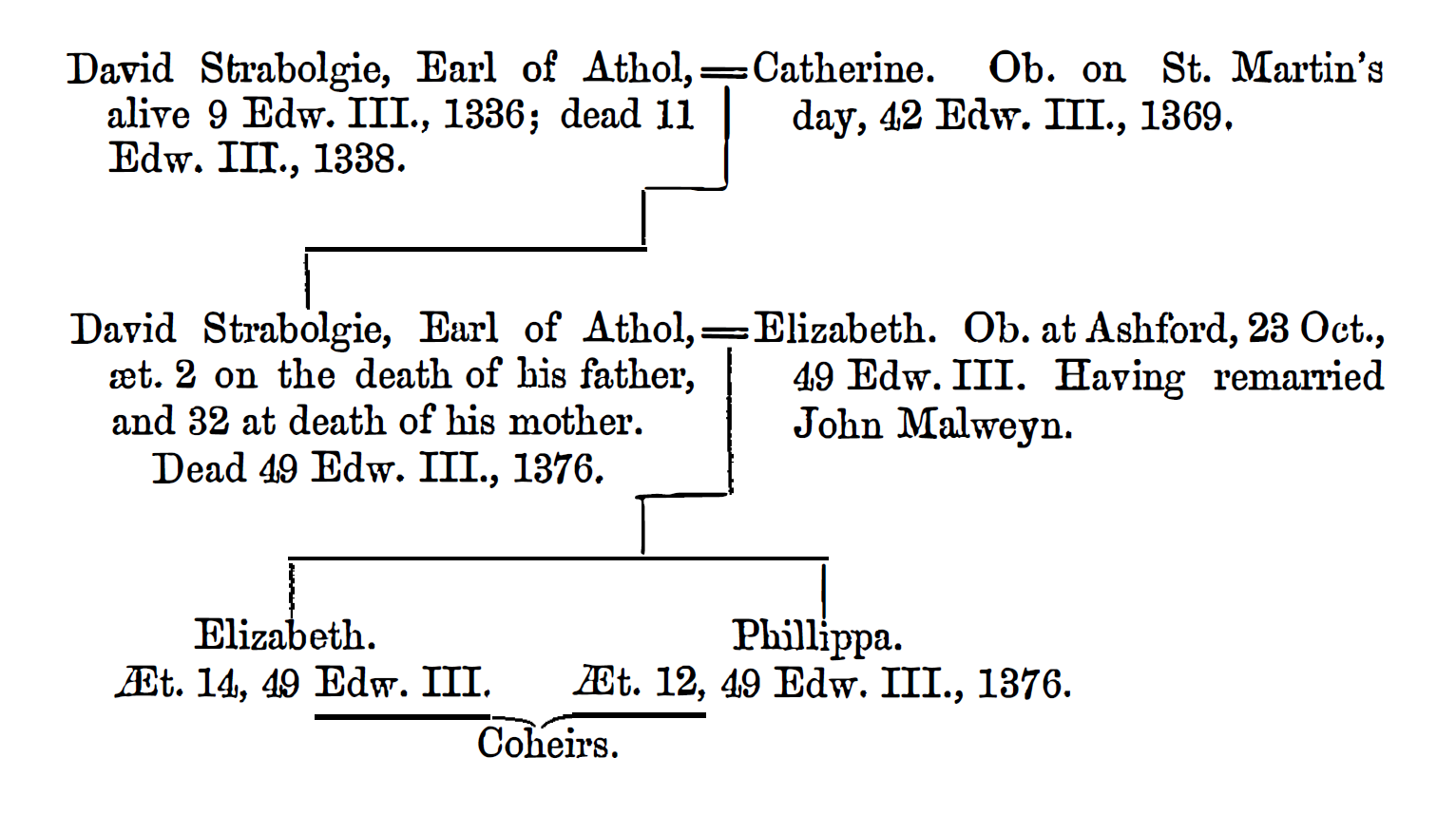

Lastly, the Ashford Brass, to a Countess of Athol, has hitherto proved of rather an enigmatical character. Weaver calls this monument the chief glory of Ashford for antiquity. It is now in a more ruinous condition than it was in the days of Dering; the greater part of the figure, the Arms of Athol, and nearly all the inscription, are gone; also the shield with the cross impaling the chevronels. Notwithstanding the acknowledged evidence of the inscription, confirmed as it is by Dering's statement that the brass was in memory of Elizabeth, Countess of Athol, and daughter of Lord Ferrers, who died October 22nd, 1375, much misrepresentation has existed. The chief pedigraic authorities have hitherto assumed that Elizabeth was an error, and that Catherine, her mother-in-law, was the person buried at Ashford, seemingly for no better reason than that 1375 was assigned as the date of her death as well as that of her daughter-in-law. After much investigation by Mr. King among the records of the Heralds' College, a pedigree by Vincent turned up, from a book marked Quid Non, which threw much light upon the question; but as Vincent's pedigree contained some grave chronological errors, I procured a search to be made among the 'Inquisitiones post mortem' at the General Record Office, and embody the results of that investigation in the following pedigraic sketch:

The return of the jury, though no doubt in the main correct, gives a slight error of about two years in the age of David the son, which however is not of sufficient importance to affect our object of identifying the monument as that of Elizabeth, the daughter of Henry Lord Ferrers, of Groby. Vincent's pedigree gives the date of the death of this David, Earl of Athol, as Oct. 10, 43 Edw. III., or 1370, which affords about five years' survivorship for his wife, during which time she is described as becoming the wife of Malweyn, of Ashford. Had the Inquisitions recorded the name as Malmain or Valoignes, the association would have appeared intelligible; the Malmains having large property at Waldershare and Pluckley, and the Valoignes great possessions at Ashford; as also had the Fogges, with one of whom, Thomas Fogge, Esq., of Ashford, she is also associated, as Hasted says, in a pedigree of Bargrave's, whom he therefore thinks might have been a third husband.

There is another pedigree in the College of Arms, in which Malweyn is given as a marriage previous to Athol. Thus although Dering marks the head-dress as Valoignes, throwing in his testimony in favour of that name, we are left to conjecture by which of her reputed husbands she found her place in Ashford. That she died there is specifically stated in the Inquisition. If he be correct, "Malweyn" in the Inquisitions and in our pedigree is a misreading for Valoignes. But the name is so frequently repeated in these Inquisitions as decidedly "Malweyn," that, till further evidence turns up, we must, however reluctantly, infer that in this instance Dering is in error.

In concluding this article, the writer trusts that if every difficulty is not cleared away, enough has been said to show the degree of interest attached to Dering's notes and sketches, and the monuments they elucidate.