Keith Parfitt, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Sheila Sweetinburgh, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Patricia Reid, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

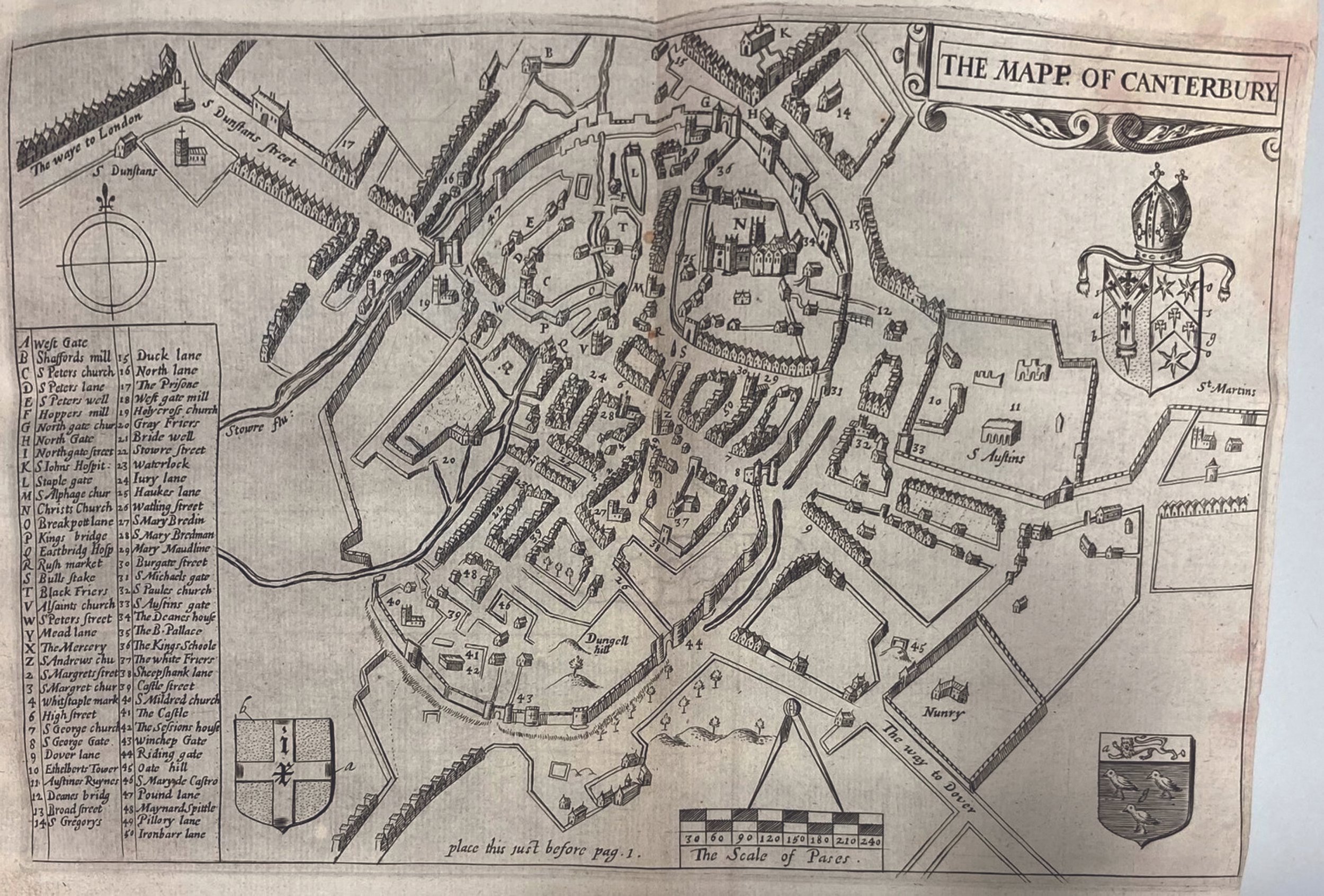

Michael Zell and Jacqueline Davies, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Tim van Tongeren, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Gillian Draper, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Stephen Clifton, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Eleanor Wilson, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

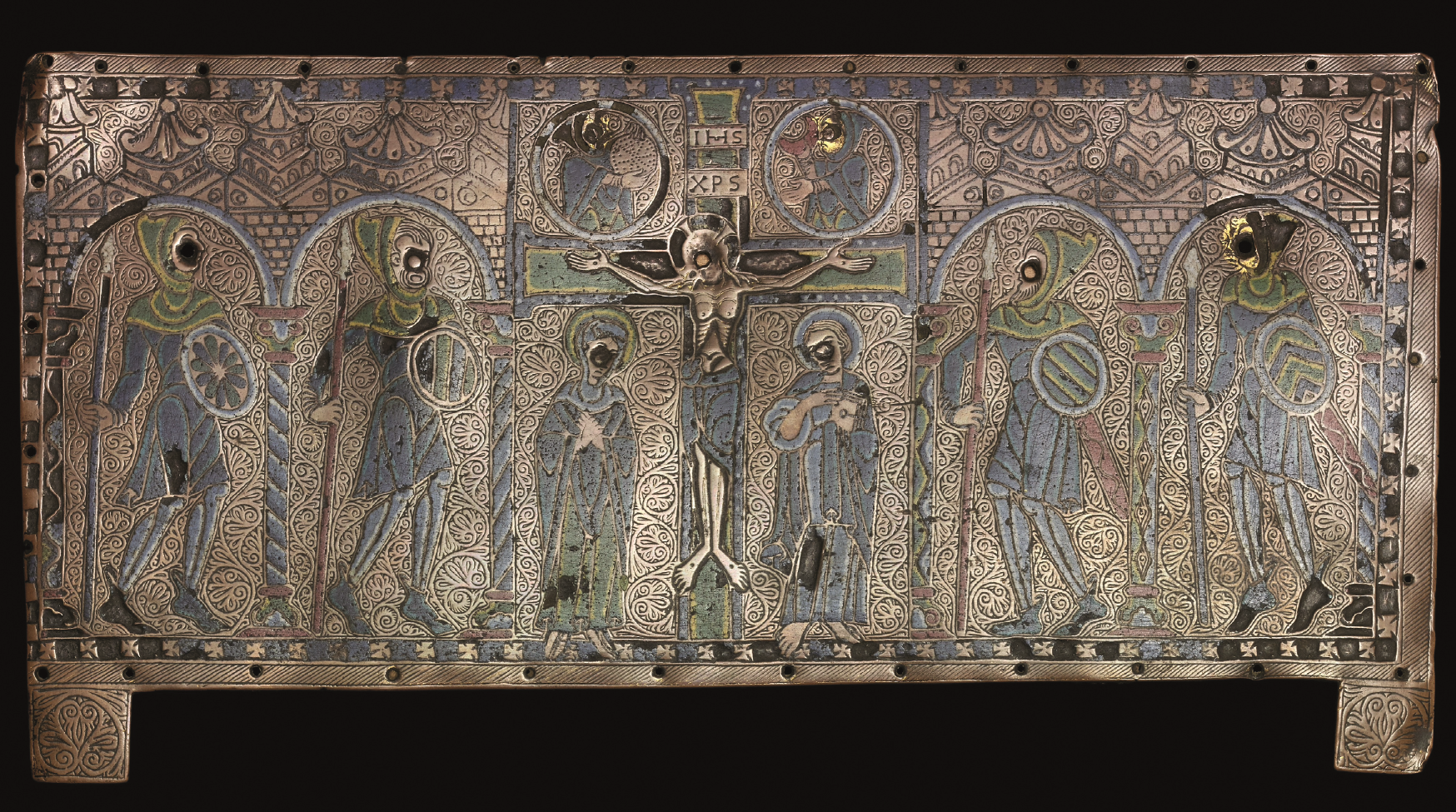

Rita Wood, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Avril Leach, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

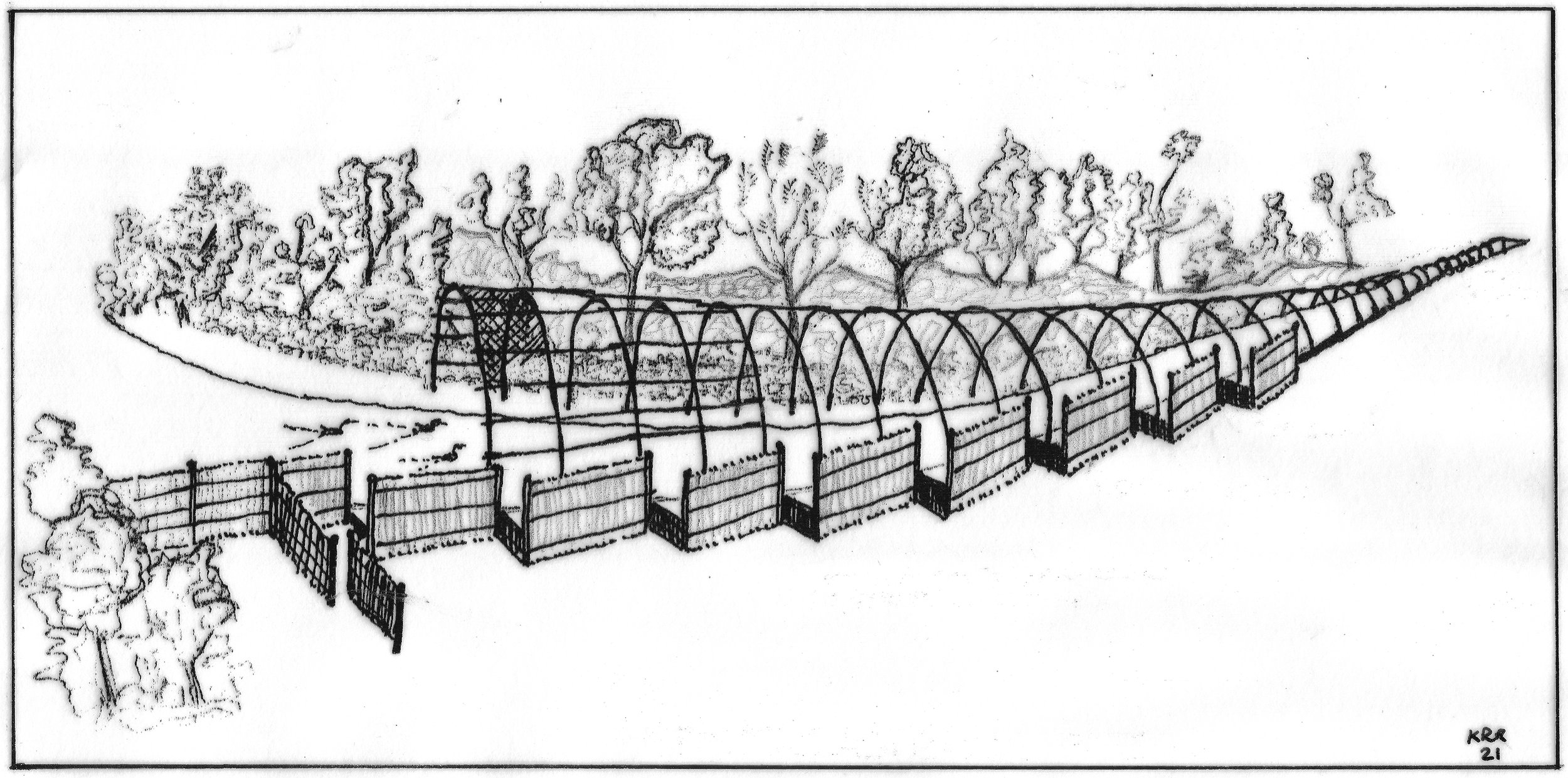

Keith Robinson, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

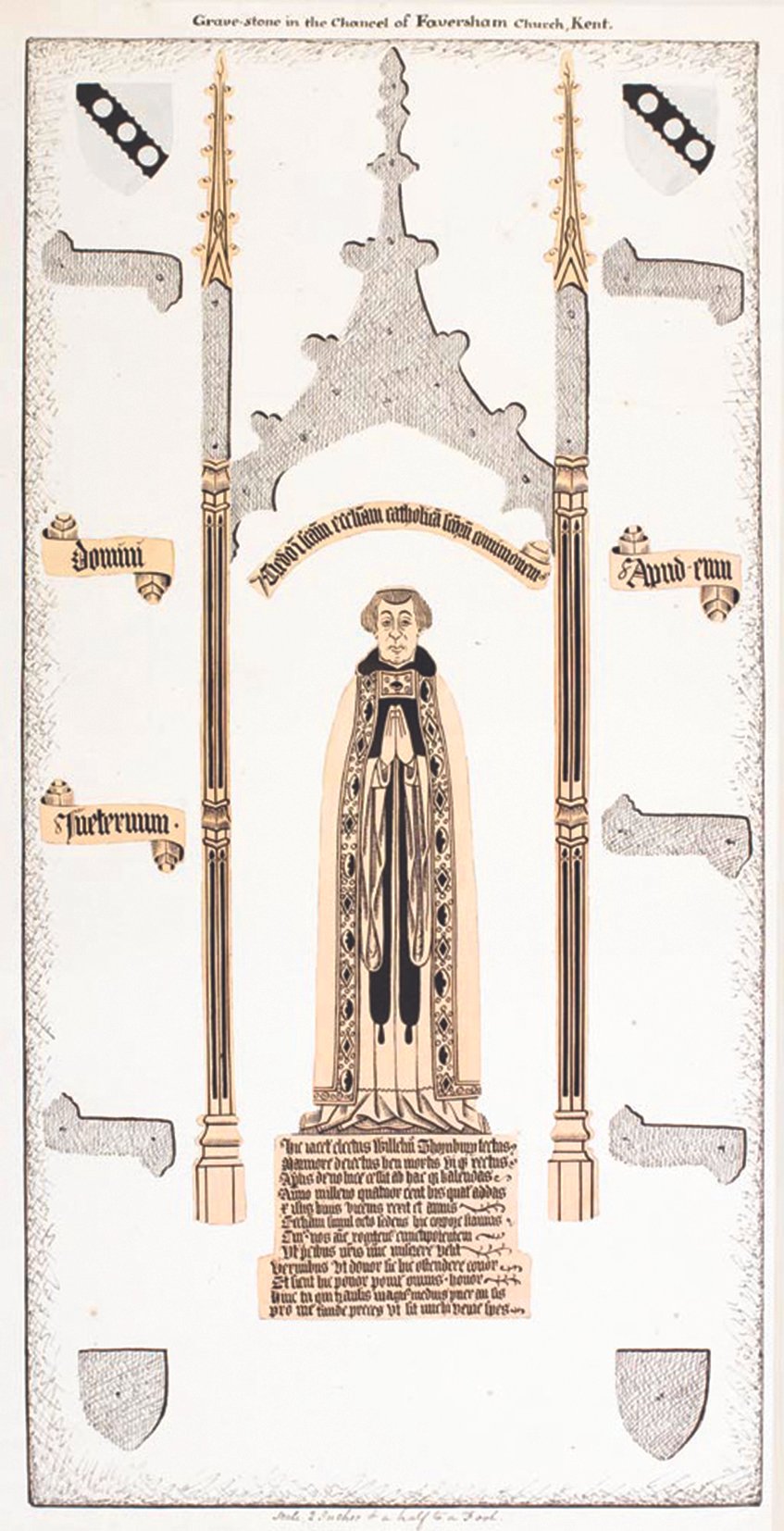

David Lepine, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Margaret Bolton, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Stephen Draper, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Pete Knowles and Tim Allen, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Stephen Williamson, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Erica Gittins, 2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

2022, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 143. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.